SCROLL FOR MORE

Discover The Queen’s College

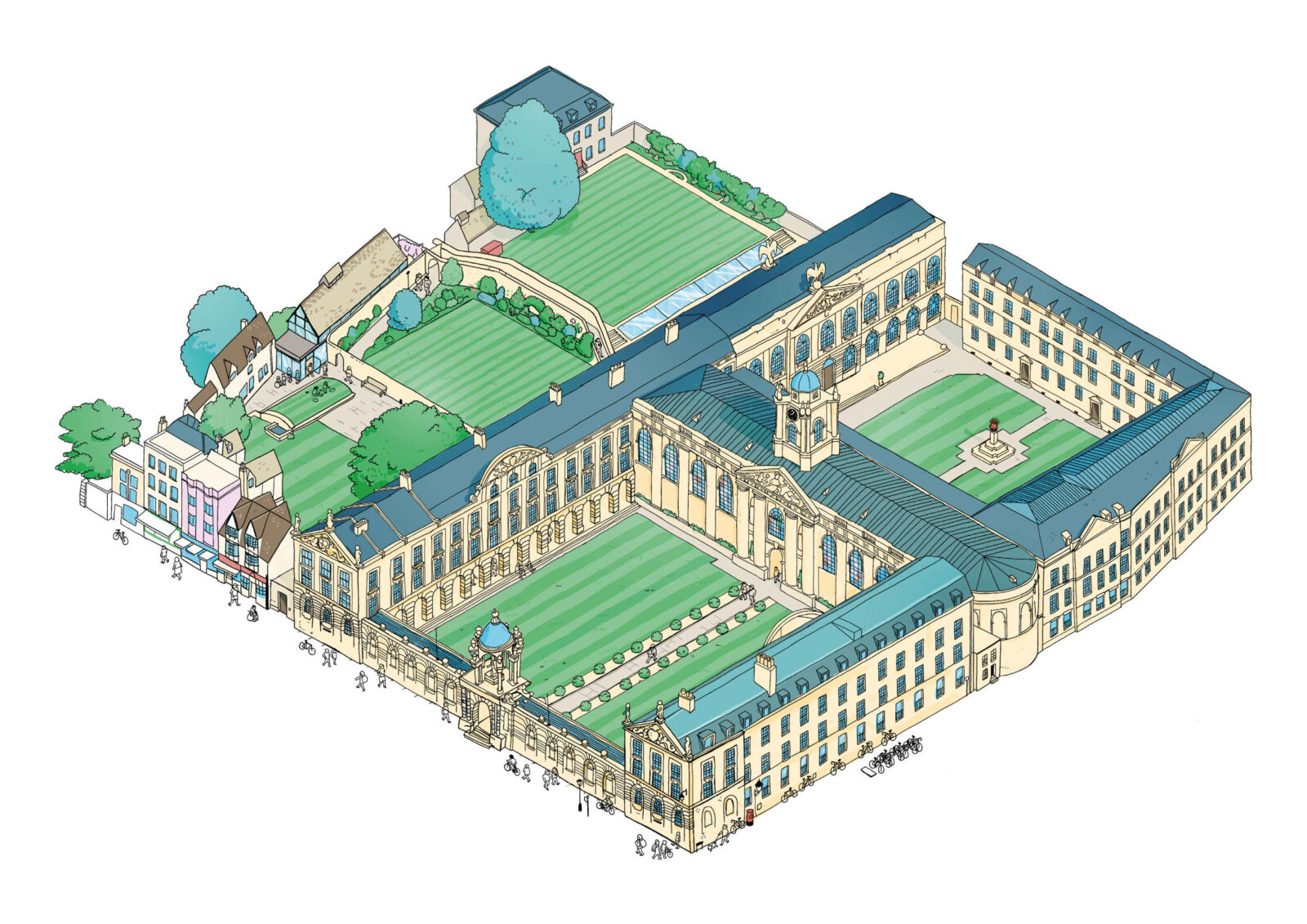

The Queen's College

is tucked away behind the High Street in the centre of Oxford

has three library reading rooms on site

is a stone’s throw from your lectures and labs

is a 15-minute walk from multi-cultural Cowley Road

Watch the virtual tour

What can we help you find?

We’d like you to get to know us a little better so please use our search to find the information

you need. If you can’t find something, please email news@queens.ox.ac.uk.