We spoke to new Fellow in English Professor Tamara Atkin about her research into the material conditions that shape literary production and reception.

Your research examines the material conditions that shape literary production and reception. Can you tell us a bit about what this means?

The really short answer to this question is that whilst there is nothing especially material about a text, its transmission is very often predicated on it being given physical form (there are some exceptions here, and even in predominantly literate cultures, there remain some genres and modes associated with orality). I’m interested in studying the technologies that enable material transmission—writing, printing—but also thinking about the ways in which the affordances of manuscript and printed textual production mediate the receptive possibilities of a given text.

I realise that might be a bit hard to grasp, so perhaps I can explain what I mean with a concrete example. In the epilogue to Thomas Dekker’s satirical play Satiromastix (1601, published 1602), Captain Pantilius Tucca encourages the audience to goad Ben Jonson into writing a rebuttal satire declaring, that in so doing, Jonson ‘shall not loose his labour, he shall not turne his blanke verses into wast paper’. What’s interesting to me about this quotation is the way that Tucca suggests that when lost or wasted, intellectual labour—that is, the immaterial work of writing dramatic poetry— is transformed into physical waste paper—which in an early modern context typically meant printed or manuscript leaves recycled for another use.

In practice, what all this means is that whilst my research takes the material text as its object of study, I try to use codicological* and bibliographical practices and techniques as a way of thinking through quite broad questions about literary production, authorial labour, and textual reception.

What are your findings on premodern drama?

The first ever texts I read as an undergraduate were the late-medieval morality plays Mankind and Everyman, and I have remained fascinated with pre-Shakespearean drama ever since then. Most critics of medieval and Tudor drama have written about the theatricality of these plays, and a lot of really great and important work has been done to reconstruct their original performance conditions. In contast, I’ve always been interested in their textual history because, when you think about it, it’s not self-evident that plays should always be written down. Do dramatic texts represent a record of performance or are they designed to enable it? When did reading drama as an activity apart from or separate to performance become a ‘thing’?

These are the sorts of questions I set out to answer in my last book Reading Drama in Tudor England (Routledge, 2018). I wrote this book because I wanted to understand the print reception and status of drama before Shakespeare et al. began writing for the commercial stage. I learnt that early on printers developed conventions for articulating drama as a printed form – by this I mean that they established norms that determined the look of drama on the printed page, like the use of stage directions to indicate stage business and speech prefixes to organise dialogue. It has often been said of these features that they encode and thereby enable performance, but in writing Reading Drama I became increasingly convinced that printers developed and used features like character lists and stage directions not to enable performance but rather to signal the idea of performativity. These readily recognizable features, these conventions, act as a guide to tell us how to read the book and imagine it as a play.

In the context of Tudor drama this point is really important because a lot of these plays are routinely dismissed as sub-literary, crude pecursors to the more literary drama of Shakespeare and his contempories. My work on Tudor drama suggests something different, namely, that as early as the 1550s and 1560s, drama was being printed for leisure-time consumption, as a genre of writing worthy of reading.

Your Leverhulme-funded work on the reuse and recycling of old books explores literary ideas about waste and reuse. What conclusions have you drawn about the role of old books in early modern culture?

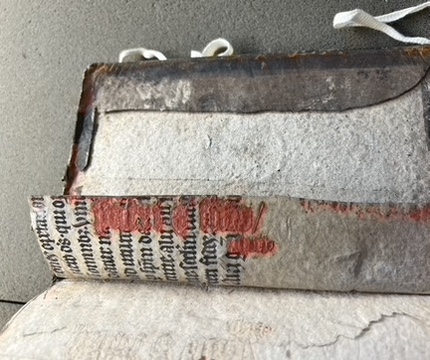

So many! Right now, I’m thinking about the ways that binding waste—which is to say, the dismembered bits of manuscript and printed texts recycled in the bindings of other, newer books—highlights the inherent instability and unfinishedness of the early modern book. All books are unfinished insofar that the making of meaning lies with the reader. But early modern books, which were typically sold stab-stitched but otherwise unbound, often with errata lists calling on the reader to correct errors, draw attention to their status as unfinished objects that required reworking.

Early modern books draw attention to their status as unfinished objects that required reworking.

Manuscript and printed waste represent examples of objects so heavily reworked that they simultaneously lose their materiality and are reduced to it. Binding fragments survive because they have been repurposed to secure the durability of other books. As fragments, however, they are also ghost-witnesses to texts that have become immaterial, incomplete, and unknowable. When these fragments coalesce with the leaves of the texts whose bindings they strengthen, they offer a stark reminder that textual value is contingent on readerly taste and judgement, and that irrespective of the author’s ambitions, all texts are subject to market forces that makes them susceptible to dismemberment and reuse.

The College’s Centre for Manuscript and Text Cultures looks at pre-modern epigraphic traditions across cultures. What observations have you made about the interactions between manuscript and print?

Like other members of the College’s Centre for Manuscript and Text Cultures, I value the ways that working on pre-modern books creates unique opportunities for inter- and multi-disciplinary collaboration. For instance, I have recently been working on a collection of books in the Bodleian once owned by the twentieth-century collector and bibliophile Albert Ehrman. The collection has some incredible early sixteenth-century books in contemporary bindings, many of which contain uncatalogued manuscript and printed fragments. Identifying these fragments – some of which have proven to be very rare or otherwise unusual – has led to opportunities to collaborate with leading scholars in other fields, which has been an amazingly stimulating and often humbling experience.

Working on the printed and manuscript fragments that turn up in the bindings of other books has also challenged me to think about the relationships between different forms of textual technology. Again, I can probably best explain what I mean by way of example. In the Bodleian, there’s a copy of a 1572 edition Plutarch’s Moralia in a binding that makes use of a fragment from an early fourteenth-century mass book as a spine support. It is clear from the heavy red ink that stains this fragment that it once served an intermediary function as a frisket sheet before it was repurposed as binding waste. For printing in red, printers used friskets, from which holes were cut out to allow selected areas of the inked metal type to be printed. In the crust of red ink on the missal fragment it is possible to make out the words ‘patri[s] ⁊ filii’ (Latin for ‘father and son’, as in the phrase ‘in the name of the father, son, and holy ghost’). These words make it clear that this frisket sheet was used for the printing of a ‘black letter’ liturgical text. Black letter is a print typeface based on a medieval handwritten script known as textualis quadrata. Though produced using a different technology, the printed words caught on the manuscript leaf therefore mimic the appearance of the handwritten missal, and in doing so, blur the distinction between printed and handwritten text.

Is there an item in the College’s book collection that you’re particularly keen to see (and, if so, why)?

It’s very hard to pick one! I’m excited to go and spend some time with the card index, as I am interested to know more about the kinds of readers who have interacted with the College’s historical collection and the sorts of ways they recorded their engagement. To give an example: I have for many years been interested in the writings and other activities of the notorious Protestant polemicist John Bale (d. 1563). The College holds several books associated with him, including a copy of an English translation, very likely by Bale, of a Latin tract in defence of the Royal Supremacy. The College’s copy remains in its original sixteenth-century blind-tooled binding, and the card catalogue enticingly notes that the margins and endleaves are full of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century manuscript notes and additions. Who was or were the reader or readers responsible for interacting with this book in this way? What can we learn about the status and value of books as objects from these manuscript additions? And how do such marks of readerly engagement nuance our understanding of religious controversy in the sixteenth century?

Alongside evidence of ownership and reading, I’m excited to think about the ways the College’s historical holdings can enliven my current research into both manuscript and printed waste, and the early modern second-hand book trade. The catalogue entry for the book I’ve just mentioned describes a calf binding over wooden boards with remnants of metal clasps. This style of binding is typical of bindings produced in the first half of the sixteenth century, and it is very common to find wasted manuscript fragments used as pastedowns on the insides of the boards. By surveying books in historical bindings, I’m excited to discover new manuscript and printed fragments that have thus far escaped cataloguing!

In my work on the second-hand trade, I’ve been making an inventory of booksellers’ notes, since these can offer a glimpse into little known or understood trade practices. For instance, in the early modern period, when books were sold second-hand, if they were especially old, big, or valuable, it was not uncommon for a bookseller to add a ‘warranted perfect’ note, guaranteeing the completeness of the copy for sale. I’m looking forward to spending time with the College’s holdings in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century bindings, as notes like these were typically added to pastedowns or flyleaves. I’m keen to learn more about the lives of these books before they came to Queen’s.

What are you looking forward to about being at Queen’s?

As you can probably tell from my answer to the previous question, the Library has a huge draw, and I am excited to work with and alongside Librarian Dr Matthew Shaw and the rest of the Library team as I get to know the collection better. I’m especially keen to encourage undergraduates to work in and with special collections with confidence, and I can see various opportunities for bringing Queen’s students into closer contact with the College’s amazing collections.

I’ve only been here since September, but it’s clear that Queen’s has an incredibly welcoming and rich community of academics, staff, and students. I’m really looking forward to getting to know colleagues and students better and building on the conversations I’ve already had over lunch and dinner to work collaboratively and across different disciplines.

Do you use the special collections in your teaching?

Yes. Last week I took my second-years to the Weston Library and we looked at a selection of early modern manuscripts, including Bodleian MS Tanner 307, a scribal manuscript containing 167 poems by George Herbert, which were subsequently published as The Temple (1633). This manuscript may have been prepared to obtain a licence for that edition, and it was fantastic for students to have the rare opportunity to compare the mansuscript and print versions. Tomorrow, we will visit the College Library to examine items selected by students that complement their work for the early modern period paper. It can be quite intimidating to work with special collections, particularly for undergraduates, and I’m so grateful to Dr Shaw for enabling sessions like this, which can really transform the way students think about and work with literary texts.

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m currently finishing a monograph, Reusing Books in Early Modern England, that considers the long lifecycle of manuscripts and books after their initial production and reception. Work for this project has been supported by a Leverhulme Major Research Fellowship, which has allowed me to spend a lot of time digging around in libraries and archives – a huge luxury! Once finished, the book will bring together several of my longstanding interests: the cultural and intellectual habits formed by the Reformation; early modern book history; and the interplay between material and metaphorical language. It’s been enormously fun and rewarding to research, and I am now enjoying the challenge of turning that research into a piece of long-form academic writing.

My next project is about the early modern second-hand book trade, which surprisingly has been very little written about. I’m currently putting together an application to secure funding for a team to undertake this research collaboratively; it’s a big and ambitious project and will benefit from scholarly expertise across a range of different areas. I want to know who bought and sold second-hand books, where they came from, how they were valued, and what role they played in the making and unmaking of both private and public collections. In answering these sorts of questions, I think we can begin to challenge conventional wisdom about the English early modern book trade, which has mostly focused on new books produced in London.

Can you recommend a book?

This is such a hard question. I’m going to do my best not to squirm out of it, so will recommend The Safekeep by Yael van der Wouden. Why this book? For me reading is so often a professional activity, something I do at a desk, in a study, or in the library. I read this book on holiday, largely whilst lying in a hammock next to a swimming pool where my children were playing. I’m sure part of the pleasure I took in reading it was in the heat of the air, the nearby sounds of my children, the whole aural and sensorial experience of being at rest. And as I lay, prone, reading, I enjoyed the way that van der Wouden was able to manipulate my response to the main character.

I started out with little sympathy for Isabel, a young woman living in a rural area of the Netherlands in the aftermath of the second-world war. She seemed pettily parsimonious, obsessive, and controlling. But over the course of the novel, as she struggles to come to terms with her mother’s death, with her insecure hold on the house she calls home, and with her feelings for her brother’s girlfriend Eva, I found myself liking her more and more, becoming increasingly invested in her material and emotional fate. Add to that the wider context of life in postwar Holland as the country struggles to make sense of the years of Nazi occupation, and I found it a compelling and thrilling read.

The Safekeep was one of the first books I read on my new Kindle. As I’ve already indicated, I’m really interested in thinking about the ways different textual technologies mediate the reading experience – how reading a printed book differs to reading a manuscript book—and I think these sorts of questions are equally pertinent to newer forms of text. Reading novels on my Kindle is great for travelling, but I miss the tactility of holding a book, of flicking back to cross-check a reference, and I love that my physical books hold traces—in dog-eared corners, forgotten bookmarks, the occasionally underlined word etc.—that record my experience of reading them. I’m not getting rid of my Kindle just yet, but if anything it’s reminded me how great – how irreplaceable – books are!

*Pertaining to the study of the book; taken from the Latin word codex meaning book, codicology refers to the study of the whole manuscript book, all its physical and historical characteristics