At 16, Peter Chauvel was fishing off the coast of Alaska when he saw something that changed his life: plastic waste drifting into one of the wildest places on earth. Years later, that moment would help take him from commercial fishing boats to Queen’s, and on to X, Alphabet’s Moonshot Factory, where he now works on technologies designed to eliminate waste entirely.

In this interview, Peter (MBA 2021) reflects on the journey that shaped his career, the value of cross-disciplinary thinking at Queen’s, and what it really takes to work on problems most people say are impossible.

You started out as a commercial fisherman. Can you talk us through your journey from there to the Moonshot Factory via an MBA at Queen’s and what motivated you along this path?

I actually got into commercial fishing because I wanted to pursue athletics. My school team got absolutely pummelled by another school during a rugby match, and I decided I wanted to go to that school instead. I took a bus, walked into their admissions office, and they said, “That’s not really how this works.” It turned out it was a private school. They assumed my parents had sent me (they definitely hadn’t!) but after speaking to them, the school said they wanted me anyway. I just had to find a way to contribute financially myself, so I turned to fishing, working all the way up from Vancouver to Alaska.

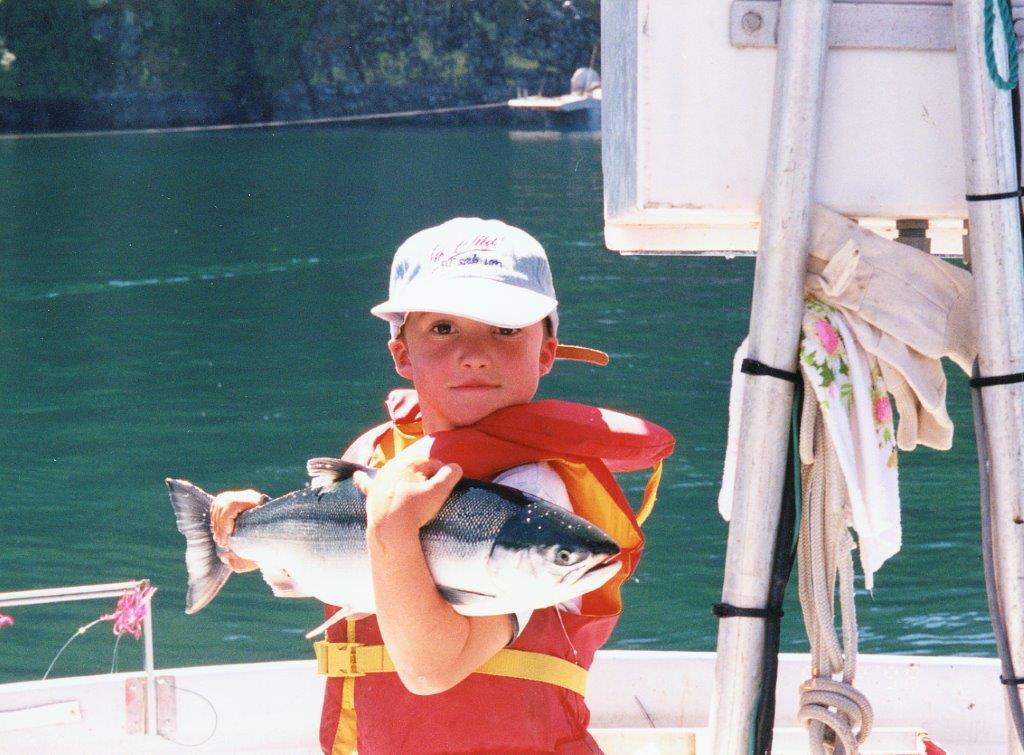

I mention this because Alaska is what set me on the path to the Moonshot Factory. I was fishing there in the years before and after the Japanese tsunami. Before, it felt wild like Jurassic Park with whales, sharks, and bears. After, all of that was still there, but so were huge amounts of plastic that had floated across from Japan.

I was 16 and thought: one day I’ll want kids, and I want them to see this place the way I did. I didn’t know how to fix plastic waste, but I was sure there had to be a solution, and a business case for it. That led me to study political economy, international business, and economics, all focused on resources, energy, and the environment.

After that I worked as a consultant with farmers and fishers, then on projects stopping plastic from reaching the environment. Eventually my brother joked, “You went to Oxford: apply to Google so we can say we did.” I applied to a generic intern role, interviewed for a then secret project on a future without waste, and that’s how I ended up here. A lot of luck, good timing, and a 16-year-old’s ambition.

For people who don’t know, can you briefly describe what Moonshot is and why it exists?

The Moonshot Factory was established by the founders of Alphabet and Google with the goal of creating Google-scale businesses in the whitespace where Alphabet or Google didn’t exist. The first moonshot was the self-driving car born from the radical idea that since there’s a lot of human error in driving, we could make roads safer by removing the driver entirely. From there, they expanded into other technologies like Lambda, one of the original generative AI platforms that eventually became Google Brain (and later Gemini, part of Google Deepmind). Many of the team members from that spun out and created Open AI, Anthropic, etc..

At first there was a very heavy focus on creating ‘cool new technologies’ at the Moonshot Factory. As time went on, the realisation was that we should focus on solving the world’s largest problems, and using technology as an enabling factor. Today, X, the Moonshot Factory is focused on the triple Venn diagram of a huge problem, a breakthrough technology, and a radical solution.

The project I’m part of is called Materra. Materra’s objective is to create a future without waste, where we use the products of yesterday to make the products of tomorrow. One initiative we’re working on is with Dow Chemical to identify and sort very complex materials such as film plastic and flexible plastic. For example, crisp bags and meat packages often have multiple layers in them that make them very difficult to recycle. While these layers aren’t visible to the human eye, we’ve developed a technology that can see them and enable sorting and recycling to recover these plastics. The recycling rate on film and flexible plastics is currently only about one percent.

How did your time at Queen’s influence how you approach the ambitious or unconventional projects that you face now?

More than anything it was the diversity of people around me. I chose Oxford and Queen’s because, unlike a traditional MBA where you’re surrounded by other MBAs, the college experience puts you in daily contact with people from a wide range of disciplines. I had dinners with people who were Biochemists, Political Scientists, Philosophers and those different perspectives helped me look at things slightly differently. It gave me a variety of challenging and interesting conversations and also helped going into the entrepreneurship environment where there is no clear pathway. We’re building new companies and there’s no clear set of rules for how to do this. Everyone has their own way. Diversity of insight and perspective is probably the best thing you can have because you’re going to be figuring out as you go and building the plane as you fly it.

Diversity of insight and perspective is probably the best thing you can have because you’re going to be figuring out as you go and building the plane as you fly it.

What skills or mindsets should students cultivate now if they want to work on big, uncertain, high-impact ideas?

Curiosity is probably the most important trait. Failure is inevitable in building new things. We fail all the time, and that’s a bit of a cliche because everyone hears that in entrepreneurship, but it really is true. The only thing that keeps you going when everything goes wrong is the idea that there might be a right way and that there might be an interesting or different way.

It’s also important to understand that you need to respect everyone in their roles. Some of the best people you work with come from some of the most unique backgrounds, and some of the most important people have hands-on experience but perhaps not the same level of education as you. My role has been defined by being the bridge between those who are highly educated, because I spent time with those very highly educated, smart individuals, and those who have more hands-on experience. In fisheries, we used to have a mechanic who said to me, ‘Peter, you have to stop using your 10-cylinder words around me’. That was a somewhat enlightening experience because many of the things that are successful in modern business, and change the paradigm, are built by people who have unique backgrounds or direct experience, not always the most degrees or education.

Curiosity is probably the most important trait.

I’d also recommend having a global experience. A lot of the world’s challenges and opportunities require global understanding. Building a unicorn or mega business or amazing nonprofit, whatever it may be, requires a global perspective and so getting that experience and understanding different issues (I’ve lived in six countries and worked in over 10 on different projects) helps shape your understanding of how to do things. Everyone dives very deeply into technology, so being able to step back and say, ‘but do you understand how that would work in sub-Saharan Africa or in America?’ is vital.

What did you enjoy about your time at Queen’s?

All of it. It was amazing. I look back at my experience and it was a hugely formative part of my life. My last memory of being there was of the Queen’s Ball, which I loved. I spent a ton of time in the MCR because I had such an interesting group of fellow MCR people. I also got involved in athletics and I played on the baseball team because I wanted a second Blue (I thought they had the coolest blazers!) and that gave me exposure to a broad array of people I wouldn’t otherwise have met. I had so much fun going to the Oxford Union for debates and drinks; it was an experience, I think, unlike anywhere else. Queen’s itself is a fantastic institution. The library, while freezing at times, is an amazing place to work.

Moonshot thinking is often described as solving “impossible” problems; how does that actually play out in your day-to-day work?

It’s very easy to get beaten down in this environment. Mentally, you can get fatigued because everyone tells you, it’s impossible, you’re not going to solve it, you’re not price competitive…I’ve heard every excuse as to why something won’t work. My personal belief is you just need one excuse for it to work to keep pursuing it and, consistently, we have found enough breakthroughs. Those breakthroughs, whether they be business breakthroughs, technology breakthroughs, or market breakthroughs, bring conviction that what we’re doing can make a difference.

That being said, there’s something else about the Moonshot Factory that I respect, which is something called a kill criteria. The kill criteria says if you can’t hit these objectives within these given times, the project will not work at some point. There are things that we’ve achieved as a factory that we have killed because it just didn’t make sense. We had a project related to extracting water from the air in sub-Saharan Africa so people didn’t have to go to wells, but we couldn’t make it cheap enough for the market. In that case we made the designs and information public for potential use as a philanthropic effort. We also tried nuclear fusion, and we successfully did it, but we could never make the economics work so we published the way in which we did it, and there were hopefully enough breakthroughs there that someone who is close to making it work will learn something from that.

I think you have to be intrinsically motivated, you have to say “I’m willing to try this, knowing there is a very high probability it will fail”. We have a huge advantage versus entrepreneurs, because we have Google and Alphabet resources and a safety net but that’s not why I’m here. I’m here because we get to take on huge challenges with the resources of a company like Alphabet. Each day I keep in mind that we have the opportunity to try and change something and I remember that the reason I started all of this was that teenage kid who saw those plastics in the ocean said, I don’t want this.

Each day I keep in mind that we have the opportunity to try and change something and I remember that the reason I started all of this was that teenage kid who saw those plastics in the ocean said, I don’t want this.

How do teams decide whether an idea is worth pursuing, shelving, or letting go—even if people are deeply invested in it?

There are two things that we’re asked to do on a daily basis which I think are core. The first is to be passionately dispassionate: be as objective as you can humanly be in what you’re working on. The reality is that people were brought here not because they’re the best expert in plastics, but because they have a mindset that meshes well with the Moonshot Factory ethos. Second, fall in love with the problem. It’s very easy for someone to build something and say, this is the solution, and they love their solution. The reality is it’s probably wrong. It’s probably not the right solution, or the right time, or the right technology, or the right market. So, we’re asked to fall in love with what we’re trying to solve, not how we try to solve it. This means being iterative and changing things. The Factory wants you to be wrong in order to get closer to being right. One of my goals as a business strategy and operations lead is to figure out all the bad pathways, because I don’t know the right one. In the billions or trillions of permutations of actions, it’s hard for me to pick the right one. But if I can start to eliminate wrong ones, it leaves a smaller search pool for us to go into.

Fall in love with the problem.

At Queen’s we also try to get people to think differently and across disciplines. What do you think are the most important things we can do to create the best environment for this culture?

I think one thing that breeds true for both institutions is the value of cross-disciplinary discussion. Jokingly, I was once called the objectively least technical person here. I have no engineering background. I have my grade nine sciences. But through interfacing with people who are exceptionally technical, I’ve learned how to discuss these topics. I learned how to understand them, and while I don’t have a formal degree in it, many people would probably say that I’m a Materials Scientist and that is from exposure to these different groups. I think we’re at something of an inflection point in society where AI will play a role in the future. What role it plays, I think, is still undecided, and I don’t have a strong opinion but I believe it has a role in the future, and it will change the way in which we operate.

Learning about the aspects in which AI can be leveraged in each individual’s environment is very important. I think the best thing the College can do right now is look at how it can bring in experts who understand the applications to teach people. The detail is changing on a daily basis but the fundamentals of it have existed since the mid-2010s. Giving students exposure to that will give them the opportunity to say, hey, in my subject area this could be an interesting merging of these things, and in the foreseeable future that is where you will see the growth in development of business. Going beyond a shallow understanding of AI applications will catapult students into the next generation. Obviously, this is coming from a guy who works at an AI company so I am definitely biased!

On the flip side, the other thing I mentioned earlier, is to give students exposure to different environments and understandings in the real world. The UK and the US do not represent the world. Even regionally, there are huge differences in the way in which people think, act, and operate daily. Helping students realise those differences will be greatly to their benefit.

Going back to AI, do you think in general people are overestimating or underestimating its impact?

That’s a good question. I would say both. I think we underestimate its impact in certain areas, and we overestimate its general impact. What people think of when they think of AI, in my opinion, is something like ChatGPT and Gemini search and I think we overestimate the impacts of that. I think we underestimate its impacts in specific and direct applications. It is a thing that takes huge amounts of information and draws very direct conclusions from that, which is why when people see ChatGPT and Gemini they are like, wow, I would normally have to search hours for this to get that. That’s a good application of AI, but it’s not where I think it’s going to be the most meaningful.

I think we underestimate AI’s impact in certain areas, and we overestimate its general impact.

I think there will be optimisation efforts in large industrial applications in ways of identifying societal risks in climate change applications, in energy, where there’s finite outcomes, but huge amounts of information that can lead to those finite outcomes. That, to me, is where I think we’ll see the biggest transformation. Or also things like the future of medicine, drug discovery, cancer treatments, new materials, new methods of looking at the way in which the world just generally operates. I think that’s where we’ll see the biggest changes.

At the Moonshot Factory we agree that it will be a very important part of the future but we’re looking at what it can do that might not create the flash and bang to the average person but will make transcendental shifts to the way in which the world operates. There’s a project here called Tapestry, which looks at the biggest machine in the world, the electrical grid, which was built to go one direction – from power stations to people’s homes. But now we’ve got home solar and other new energies and it’s now required to go in a new way that it’s never done before. If we could optimise that, what would it look like? What would it look like to use every electron now, rather than losing or storing them? We could perhaps better optimise these things, the price of energy could come way down. We may be able to add much more electrification. We might be able to move away from coal. None of this is simple but the scenarios leverage what AI is best at.

How can students learn to be comfortable with the idea that their future job may not exist yet?

Funnily enough, before this interview I was reading a post by Eric Schmidt, the old CEO of Google, who said that the future isn’t in AI, the future is human. I tend to agree with him. I think that jobs will change, inevitably, but I don’t think a lot of students are going to be without a job. AI is very much like a student: you teach it things. The thing is, it learns a lot faster than you do – what takes us decades to learn, it can learn in minutes. That being said, it’s not a thinking tool right now. Maybe it will get there, but it is not today. On that basis, one of the big areas, because I’m a business student, is consulting and the idea that AI is going to be the consultant of the future. To a degree, it can do the analytics you need it to, it can understand information, it can provide feedback, but it doesn’t think beyond that. Humans will always have a role in this. We have to define where these technologies go, we have to know how to leverage them, and we have to see opportunities. It does not see opportunities – it optimises given constraints.

So, don’t worry, students! The students of today are the best prepared for this new world. What I would ask is ‘what can I do in this new environment that’s exciting?’ What it may do is open humans up to more creativity. There may be more places like the Moonshot Factory where you say, what can I leverage this to do? Rather than just saying, I’m going to sit here on a spreadsheet and do these heavy quantitative calculations that it is very good at. What I personally love about this is the idea that we’re trying to find problems that need solving. That, I think, will become a more pervasive part of society. We now have an exceptionally powerful tool that can allow us to solve problems that we couldn’t even comprehend solving before. For example, Alphafold is a project that looks at protein folding. This brings massive changes to the way in which the world operates. We haven’t seen it fully play out yet but it is bringing a seismic shift to the way we look at drugs, materials, chemistry, biology, everything in the world. And there will be many more opportunities like this for people to uncover and that’s exciting.

The students of today are the best prepared for this new world.

How can individuals outside of a place like the Moonshot Factory make a difference to the world’s big problems?

Most of the biggest challenges we face today are systems challenges. Technology can enable progress, but it is never the solution on its own. Issues like recycling, energy, cancer or drug discovery require coordinated action across individuals, businesses, and governments. Everyone in that system has agency. A correctly rinsed item in the right bin creates an opportunity—for sorting, for recovery, for value—whereas a mistake closes it down. New UK policies will strengthen these chains by creating financial incentives to collect recyclable materials and by pressuring designers to move away from non-recyclable products. Change happens through these small, cumulative actions working together. Each decision creates an opportunity, and those opportunities, multiplied across the system, are what ultimately drive change. The impact is greater than the sum of its parts, and every participant in the value chain is a changemaker within it.

We’re talking about a circularity of use where we can continue to use things instead of always creating more. One of the core parts of our project is that there really is no such thing as waste. Any product that you use, we either grew or extracted from the ground, the components that make it up, we then refine them and make these highly refined specialised products like an iPhone, a laptop, a coffee mug, whatever it may be. Then what we do is we throw that in the ground and say, well, that’s waste because it’s broken or done with. In that given item are the things that we need to make the new version of that tomorrow but to date we have really struggled to be able to extract them. We’re good at building it into products, really bad at breaking it down back to the building blocks. The reason we’re really bad at breaking down is that we didn’t give it a chance to get broken down. We didn’t give the people the opportunity. We didn’t put in the right policy. We don’t have the right technologies.

One of the core parts of our project is that there really is no such thing as waste.

That being said, in each of those areas we do have a solution, we just haven’t pulled them all together. That’s where the system problem has come in: we’ve thought linearly for so long that we need to break that mindset and give things a chance to enter that chain and to become circular. We are here to support that effort, but we need people to buy into it. We need people who sort waste – the people who work in the waste-picking facilities are equally as important as we are. The rubbish truck and recycling truck drivers are agents who can help us do this. Our dream state is that instead of having landfills, all those goods that are going there are what make the products of tomorrow rather than going to some far-off destination and mining or growing things just for the purposes of making an iPhone or coffee mug.

Can you recommend a book?

William McDonough’s Cradle of the Cradle. It’s a great book about circularity. But really my advice is read what you enjoy. You can learn about all kinds of stuff through effort and time but when you have your free time and you’re sitting there, read about something that brings you enjoyment.

Read about something that brings you enjoyment.

On my drive today I was listening to a podcast about Costco. It has nothing to do with my work, but I liked it because it was so interesting. The people who built Costco did so on the basis of the idea of ‘save people money and treat your employees well’. That business ethos is something you don’t see very often. You might hear other people say it but this is literally engrained in their top two tenets. Creating shareholder value is like their fourth tenant – in Silicon Valley, where I exist, that’s number one for everyone. Wall Street, that’s the biggest thing. The guys who worked as warehouse employees and baggers at the original grocery stores now run one of the most successful companies you’ve ever heard of and they do so on the basis of ‘help out those who are buying things and help out your employees’.

Don’t just do what I tell you to do because I got a job at a cool place because that wouldn’t work for you. Do what you like. One piece of advice I will give though is stay in touch with your friends. Your Oxford experience will go by in a flash, but they will be your friends for life.