The Mystery of Cuthbert Shields, ghost of The Queen’s College Library by Felix Taylor, Library Assistant

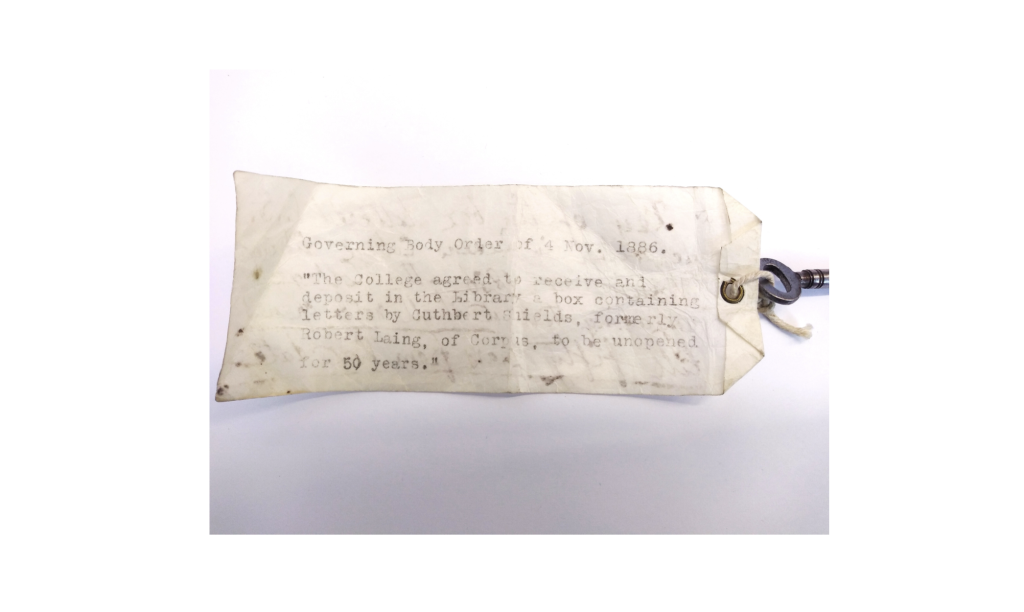

The story goes that a man named Cuthbert Shields, Fellow of Corpus Christi College, left a key and a locked tin box to the College Library upon his death in 1908. His will instructed that it was not to be opened until 50 years had passed.

For half a century a succession of Fellow Librarians waited obediently for the embargo to end, and in 1958 the box was taken to a stall at the back of the seventeenth-century Upper Library where finally it was unlocked. In attendance were the Fellow Librarian, the Bursar, and a professor, who discovered several bundles of papers, mostly letters, written in spidery black handwriting. They left, taking the box with them, but as they descended the stairs, the professor asked who the fourth member of the party had been – an old man with white hair who had been with them in the stall. Neither the Fellow Librarian nor the Bursar had seen anyone.

The next purported sighting of Shields was by Helen Powell, the College Librarian during the 1970s; according to her account in Rob Walter’s Haunted Oxford (embellished for effect, but aren’t all ghost stories?), she claimed to have seen a young student enter the library accompanied by an elderly gentleman with white hair, wearing a long coat. When confronted about this unauthorised guest, the student denied bringing anyone in with him. The old man, meanwhile, had vanished – of course.

So there we have it: the two best-known sightings of the spectre of Queen’s College Library. There have been more since, mostly rumoured and unrecorded, and his story is now part of university legend. Shields is a regular feature of the Oxford Ghost Tour operating from Broad Street, and several years ago was the subject of an episode of a folklore podcast. But who was the real Cuthbert Shields? Why did he leave Queen’s his papers? And, impossible though it is to answer, why does he haunt Queen’s and not Corpus Christi?

Robert Laing the reformer

The basic facts of his life are easy enough to assemble. He was not always called Cuthbert Shields, but was born Robert Laing in March 1840 in North Shields, Northumberland (now in Tyne and Wear), the eldest son of a mariner. Laing was educated at various schools in Germany before matriculating at Wadham College, Oxford, in May 1859. He graduated with a first-class degree in Law and Modern History, and taught at nearby Radley College until he was elected a Fellow of Corpus Christi in 1868.[i]

During this period Laing helped to achieve sweeping reforms of the teaching of history at Oxford. As a lecturer in Modern History, he collaborated in an intercollegiate lecturing scheme that led to the formation of a History Tutors’ Association in 1869. The scheme drew complaints from the History Professors, whose own lectures had become resultantly less popular, but eventually they conceded to the new arrangement. The ‘college lecture’ declined and died, gradually replaced by the personal tutorial. Laing himself held lectureships in nine Oxford colleges, Queen’s included. He also began contributing articles to The Quarterly Review, including a long essay on the work of the novelist George Eliot, whom he considered ‘a woman of genius, second to none in our century’.[ii] He loved theatre, and belonged to Corpus Christi’s dramatic society, the Owlets Club, where his recitals of Keats’s ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ and Poe’s ‘The Tell-tale Heart’ were celebrated.

Laing continued to advance the teaching of Modern History in Oxford throughout the 1870s. In 1875 he gave a paper (to a society whose senior member was J. R. Magrath, soon to be Provost of Queen’s), advocating for a reorganisation of the way individual subjects were taught throughout the University. ‘Colleges should once more be allowed and encouraged to act in the spirit of founders’, Laing declared, ‘to adopt the great modern subjects, and to amply endow criticism and erudition’.[iii]

Colleges should once more be allowed and encouraged to act in the spirit of founders

The paper was published the following year as Some dreams of a constitution-monger. Laing also threw his support behind higher education for women and began lecturing in Oxford and nearby towns. During a course of lectures on the French Revolution, he encountered Alice Liddell, now a grown woman, who had been an inspiration for Lewis Carroll’s Alice books. An infatuation developed that was not reciprocated. Laing became obsessed with her, even claiming to see sinister messages in daily newspapers which he connected with Alice and himself.

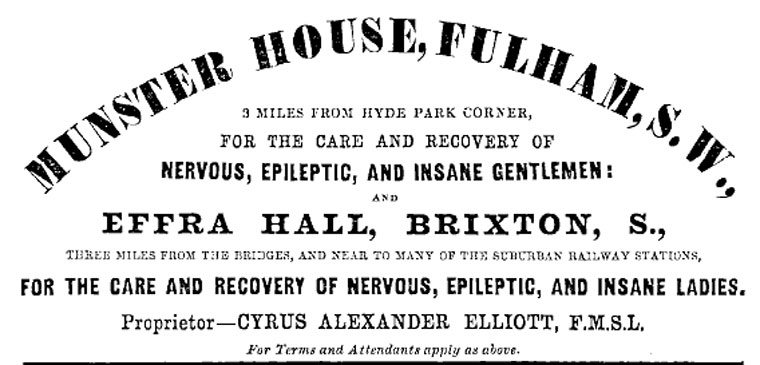

He continued to lecture until 1878 when he fled the University following a public breakdown, possibly from the combined strain of his romantic obsession and his campaigning for Liberal candidates in the parliamentary byelection (he is supposed to have shouted ‘Remember Eve!’ to a crowd outside the Radcliffe Camera). In his confessions he maintains that he was ‘driven out of Oxford’: ‘The walls of the domestic architecture of the Corpus Chapel seemed to shrink to the casings of a padded room & then expanded until the whole skyline was reached & above all Oxford congregations, there had been summoned the great congregation of the stars’.[iv] Laing committed himself to Munster House, a Fulham asylum, where he was administered to by noted physician George Fielding Blandford.

The Jerusalem prophecies

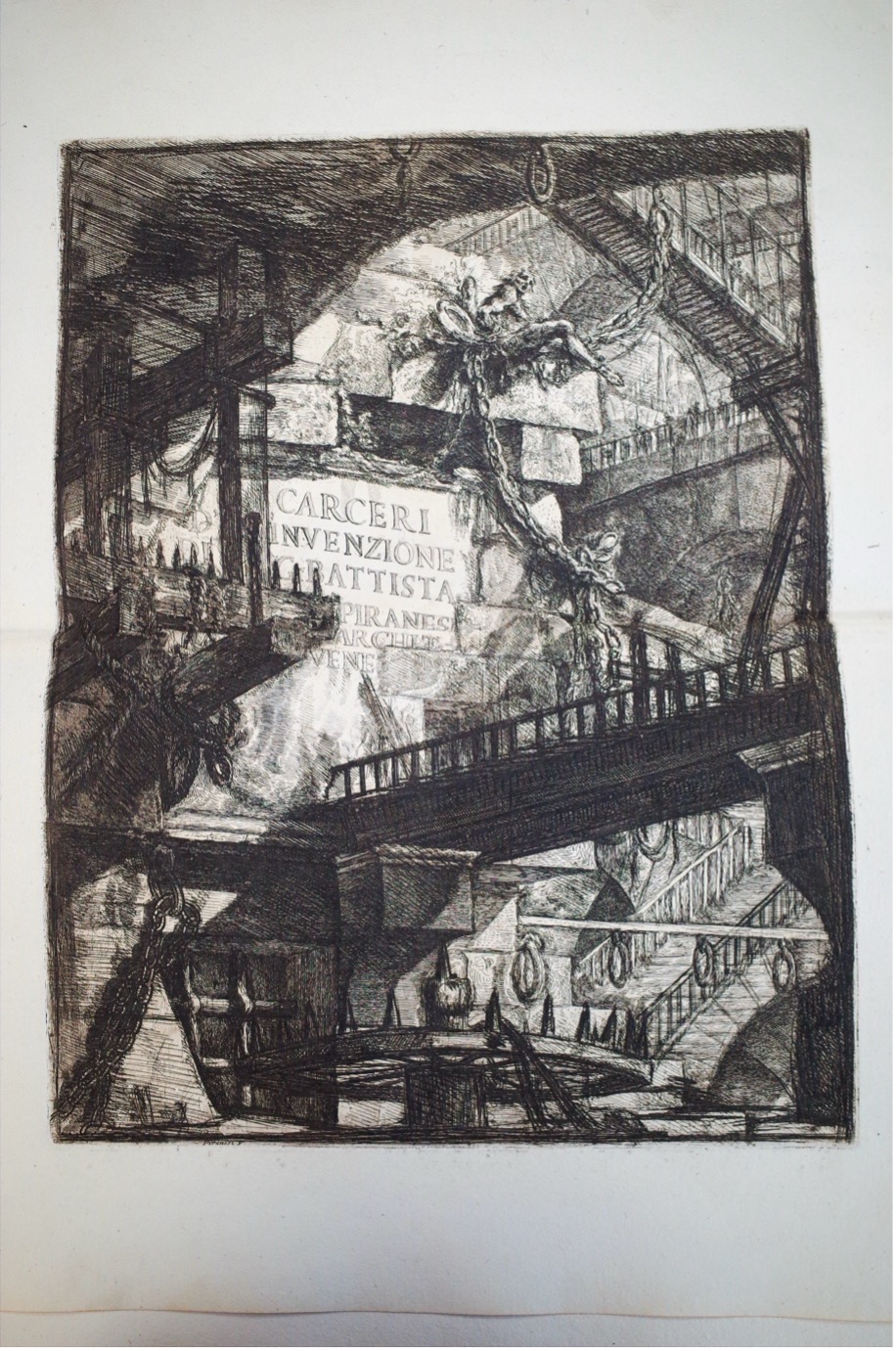

Discharged from Munster House, Laing left England ‘a broken man, yet a bold man’.[v] It was at this point, possibly in 1879, that he decided to change his name. ‘Cuthbert’ because he was born on the day of St Cuthbert, the saint of the early Northumbrian church, and ‘Shields’ in reference to his native North Shields. The new surname also contained the letters ‘I.H.S.’ in reverse (an abbreviated form of ‘Jesus’ in the Greek alphabet).[vi] By the end of 1880 he was in Gorlitz, Germany, feeling ‘ill, nervous, dejected, unhappy’.[vii] From here he journeyed to Rome, and it was around this time that he began to record his autobiography or ‘confessions’ in the form of letters to his friends F. A. Clarke of Corpus Christi and Edwin Palmer, the Archdeacon of Oxford. They were rambling and conspiratorial, full of self-pity and comparisons to persecuted historical figures. ‘At Oxford, when you knew me first, the times were like those in England, in the times Becket was chancellor, or Wolsey,’ he writes. ‘Oxford had a great chance of complete reformation’.[viii]

Shields also travelled regularly to Trieste, in northern Italy, where he would meet the British explorer Sir Richard Burton and his wife Isabel (who referred to him in a letter as ‘Cuthbert Bede’). He went further east where, according to later accounts of his life, Shields spent time with Druses (being those who adhere to the Abrahamic Druze religion; this may have been where Laing picked up his belief in reincarnation), and was apparently ‘worshipped as a god’ by them.[ix]

But the strangest single episode of Shields’ exile happened while on a trip to Jerusalem where he made a number of prophecies that subsequently came true. In April 1885, Shields was staying at St John’s Hospice and overheard four German artists discussing their intentions to paint a panoramic view. He approached them and explained that he was gifted with second sight, and asked if they would like him to make some predictions. Shields urged the painters to write down everything he had said, which they then did. Among the predictions he went on to make was that the panorama would be a success, but that it would ‘bring detriment’ to one of the painters within 5-10 years. The painter named Krieger would marry on his return to Germany but then quickly divorce. Shields also suggested that another of the painters, René Reinike, might have been an Arab in a former life.[x]

Shields soon left the hospice, and the painters thought no more of him. But in 1891 Krieger was suing his wife for divorce, and the artists realised that many of the predictions had indeed come to pass. The incident was discussed at length in an article first published by Walter Bormann in the German periodical Psychische Studien in April 1900, and later by French parapsychologist Dr Paul Joire in Psychical and Supernormal Phenomena (1916) as an example of ‘Lucidity in the Future’ (though, Joire admits, lacking in evidence). Talk of the prophecies even circulated within spiritualist circles, and Joire’s account was reprinted in the esoteric journal Light. A decade after his death, Shields (as Robert Laing) was briefly known as a famous prognosticator.

A Different Man?

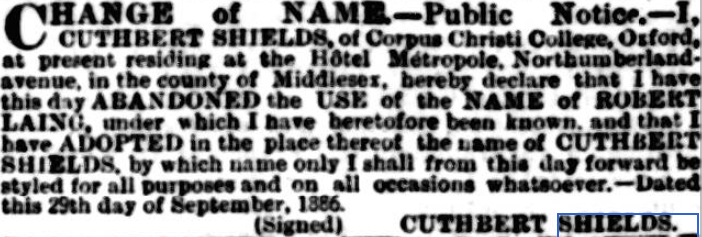

Before Shields returned to continue his Fellowship at Corpus Christi in 1886, he sent a notice to several national newspapers declaring to the world his change of name:

Now in his second ‘existence’ at Corpus Christi, Shields cultivated a reputation as one of the most eccentric figures in Oxford in the late nineteenth century. He seemed to take up his former position without event, and if this sudden reappearance provoked comment from colleagues, they kept it to themselves. After his return he became a member of the Tutor’s Club along with the classical scholar Robinson Ellis and the historian Charles Oman, who regarded Shields as ‘an interesting and amiable “crank”’.[xi] Though he was described as a ‘great Oriental scholar’, there is no evidence that Shields published anything during this period, except an affectionate portrait of Corpus Christi’s cat Tommy for Mrs Wallace’s Memories of some Oxford Pets (1900). He lectured on Dante and Goethe to the Oxford Dante Society in 1888 and was encouraged by his colleague John Ruskin to publish some of his historical lectures, but ultimately his role during these years was more ‘to stimulate productiveness in others than to produce much himself’.[xii]

Shields’ unusual interest in mysticism and the occult intensified following his reinvention. He had been known for telling ghost stories to his students at Radley College in the 1860s, but now, during dinners at Corpus, he delighted in turning the conversation to metaphysical subjects – Zoroastrianism, metempsychosis, ‘the evil spirits that haunted Rome’ – and had to be interrupted before he inevitably squashed the conversation.[xiii] Shields claimed to have lived many lives, and could trace these as far back as Zoroaster, the Ancient Iranian spiritual leader and founder of Zoroastrianism.[xiv]

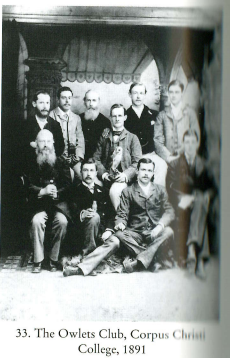

Most theatrically, he wore an ornate ring which he claimed had been given to him by a Brahmin ‘to whom he had rendered a service’ on his travels, and which he regularly used to summon visions.[xv] When Shields desired information on a particular subject, ‘he had only to look at this ring, and then he saw a picture forming before him, like a dream’.[xvi] ‘Mr. Shields devoted himself to the study of Oriental witchcraft,’ claimed one writer after his death. ‘It was his habit to give excellent dinners to a select party of friends, and afterwards to take the floor and talk of black magic until his hearers’ ‘flesh crept’. A photograph of the Owlets Club from 1891 shows Shields with a domed head and long, greying beard. Clutching a cane between his legs, his ring just visible on his forefinger, he looks fixedly into the distance as if attending to a new vision.

Cuthbert and Queen’s

Shields died suddenly from an ‘internal complaint’ on 20 September 1908 and was buried in Holywell Cemetery, behind St Cross Church. Yet the question remains: why did Shields’ ghost choose to haunt Queen’s (if choice even comes into it)? Despite his 40-year Fellowship at Corpus Christi, he seems to have maintained a fond connection to the college on the High Street. His professional connection to Queen’s began with a history lectureship in the 1870s, and Shields became good friends with J. R. Magrath, the Provost from 1878. The College’s seventeenth-century Upper Library may have appealed as a space for study or even visionary contemplation of his past lives. After his death, Shields’ books were sold at auction by Blackwell’s, but he also left a large collection relating to the history of universities and the French Revolution to Queen’s, which Magrath called one of the most important benefactions to the library after the Mason bequest.[xvii] Some were given by Shields as early as 1890, and many currently sit on the shelves of the Upper Library where his name can be read on the munificentia bookplates.

Perhaps the College had acted as a refuge for Shields in the face of his mysterious persecution in the 1870s: following his return it clearly remained a place close to his heart. This is confirmed by the fact that the tin box, which is still kept by the College, was left to the College library in November 1886 – not on Shields’ death in 1908 as is usually thought, but in the very year that he returned to Oxford. It was full of his confessional letters written to Clarke and Palmer from Rome, perhaps to sure up his reputation. Governing Body minutes record the decision to accept the box and it was duly opened 50 years later, in accordance with his wishes, in 1936. But by whom, and what actually happened?

‘If the dead can haunt us, let them’, he wrote in Some dreams of a constitution-monger in 1876. [xviii] To students and staff of Queen’s, Shields, if they know his name at all, is now just a piece of college folklore, and sensational online accounts of his haunting are riddled with inaccuracies (and appear to derive from the fictionalised account given in Haunted Oxford). Either someone saw something in the Upper Library in 1936 or thereabouts – or the story of Cuthbert’s appearance was invented around the Senior Common Room fireplace and was told and retold until its origin was long forgotten. It is entertaining to speculate. More questions present themselves, such as if Shields truly believed in metempsychosis and the rebirth of the soul – and if he was preparing for his next incarnation before his death – why would he remain as a ghost? If the librarian had waited the full 50 years, as instructed, why would this trigger a haunting? When his box was opened, was he released back into his sanctuary to remain the mystical Cuthbert Shields, loitering among his books for eternity?

Late last year the Queen’s Library team managed to locate Shields’ grave at the far end of Holywell Cemetery (a map can be provided on request). We cleared the ivy and added an entry on the website findagrave.com, where well-wishers are able to leave virtual flowers. The inscription on his headstone is from Psalm 121: ‘I will lift up mine eyes unto the hills’.

My thanks to Wanne Mendonck at Corpus Christi College for help accessing the Pelican Record articles.

References

[i] ‘Shields, Cuthbert’, Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, 1715-1886 (vol. IV), ed. Joseph Foster (Oxford: Parker & Co., 1888), p. 1289.

[ii] Bodleian Library, MS. Don e. 185, p. 35.

[iii] Robert Laing, Some dreams of a constitution-monger: a paper on university and college reform (Oxford: James Parker and Co., 1876), p. 13.

[iv] MS. Don e. 185, p. 12, 22.

[v] MS. Don e. 185, p. 20.

[vi] ‘About Men & Women’, Cambridge Independent Press (Friday 25 January, 1908).

[vii] MS. Don e. 185, p. 49.

[viii] MS. Don e. 185, p. 20.

[ix] Cambridge Independent Press (25 September 1908).

[x] Paul Joire, Psychical and Supernormal Phenomena: their observation and experimentation, trans. Dudley Wright (New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1916), p. 348.

[xi] C. O. [Charles Oman], ‘An Oxford Prophet at Jerusalem,’ The Pelican Record vol. XIV (1917-20), 187-191, p. 187.

[xii] C. P. [Charles Plummer], ‘In Memoriam: Cuthbert Shields’, The Pelican Record…

[xiii] C. O., ‘An Oxford Prophet at Jerusalem’, p. 187.

[xiv] Mary Clapinson, ‘Shields, Cuthbert [formerly Robert Laing] (1840-1908), historian and eccentric’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (8 October 2009).

[xv] Joire, p. 355.

[xvi] Joire, p. 355.

[xvii] J. R. Magrath, The Queen’s College vol. II, p. 279.

[xviii] Laing, Some dreams of a constitution-monger, p. 14.

![A book page from 1613 with the title 'Double books to be exchanged according to [the] pleasure of...'](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Double-Books-cropped.png)