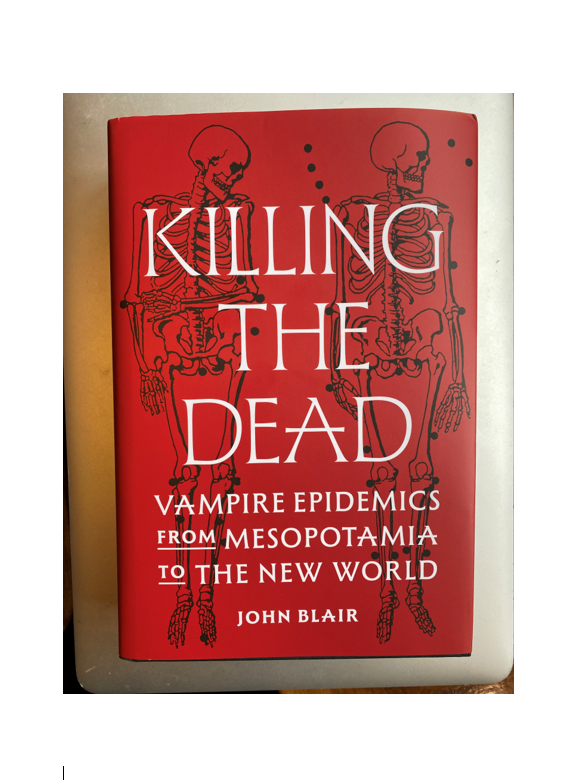

What do vampire panics, grave mutilations, and ancient demons have in common? According to Professor John Blair, quite a lot, although much of it has been misunderstood. In his latest book, Killing the Dead: Vampire Epidemics from Mesopotamia to the New World, the Emeritus Fellow and distinguished historian of the medieval world turns his scholarly gaze to the vampire.

Far from the gothic clichés of fiction, Professor Blair reveals a darker and more complex truth: that across centuries and continents, societies have enacted gruesome rituals on the dead not out of superstition alone, but as a strange, sometimes therapeutic, response to collective trauma. From Mesopotamian demonology to 18th-century Serbia, and from medieval England to modern Haiti, Killing the Dead weaves archaeology, anthropology, and neuropsychology into a gripping global history of why humans feared the undead.

We spoke to Professor Blair about what drew him to this macabre subject, what vampire panics reveal about the human condition, and why, sometimes, killing the dead is better than harming the living.

Why did you become interested in the history of vampires?

It was a coincidence. When I was an editor of Oxford Medieval Texts, I saw through the press a collection of miracles of Saint Modwenna of Burton-on-Trent written in c.1150 which referred to events going back to around 1100. Among those miracles was a cure of people who had been attacked by walking corpses. It gives a vivid account of two dead men whose corpses walked around carrying their coffins on their backs, banging on doors, and people subsequently died. Locals then dug up the two men, found that the bodies were incorrupt (free from decay), and that the cloths over their faces were stained with blood. The community beheaded them, cut out their hearts, and burned them. Afterwards, the remaining sick people recovered.

Anyway, I was reading that, and I happened to be sitting in a library browsing rather idly among the folklore section, and I found a book about 19th century Romanian folklore. I was astonished to find these same motifs recorded by folklorists from Romanian villages, 150 years ago. I thought this was an extraordinary example of the transmission of complex ideas across time and space. I became increasingly interested in the phenomena of believing in the walking dead, to what extent it’s cultural, and to what extent it’s organic and psychological. I was also interested in why the phenomena appear at certain times and not others because there’s no doubt that belief in the dangerous dead is very widespread across the world, but it’s not universal. There are many societies that have never had it and there are also societies, for example in England, that held those beliefs strongly at one point, and then they disappeared. It has an epidemic quality.

How did you approach researching such a wide-ranging topic?

I approached it in three ways. First, I had to engage with cultures and countries about which I knew very little. I wanted to make the project worldwide, so I looked at, for example, China and Southeast Asia and tried to work out if I could see a sequence of beliefs from various kinds of demon to identifying those demons as actual dead people, which is a widespread process. Second, I looked at the folkloric evidence and mythological patterns: how stories travel, how they get changed, and how there’s often a feedback loop between what people believe and literate culture. So, it doesn’t just go one way: people tell stories, scholars write them down, those books get disseminated, and they can feed back into oral culture. Third, I examined the psychological aspects. The research took me into aspects of neuropsychology, which I came to find fascinating. The research is something I’ve only been able to do in the luxury of retirement, and it’s been a great change and breath of fresh air.

You cover vampire fears from ancient Mesopotamia to modern Haiti. What do these diverse cases have in common?

The common element is the belief that the dead are doing harm to the living in the form of physical corpses. The crucial thing is that they are not ghosts. It’s the idea that either physical corpses are getting up and walking around at certain times and preying on people, or a belief, very common for example in Lutheran Central Germany in the 16th century and in New England, America in the 19th century, that the corpse is inert in its grave, but its organs are in some mysterious way doing harm to the living by causing disease or death.

Is there a correlation with events like pandemics?

Yes, there is. I conclude that there is a latent human propensity to have these beliefs given certain conditions. Freud thought they were universal but that’s clearly not the case. However, they are very widespread and I think it’s a combination of mythological, religious, and storytelling traditions which raise the possibility that this could happen, along with certain cultural elements, one of which is dominant female religious or magical specialists, or social structures where matriarchs are dominant. For example, Babushkas in 19th century Russia are people who are feared in life and there’s a sense that if certain dominant individuals are dangerous or oppressive in life, they could continue to be so after death. One very interesting point, contrary to what people tend to believe, is that the great majority of the dangerous dead have been female, not male.

The other factor is trauma, and the trauma can take various forms. It could be in the form of disease, like plague in early modern central Europe, or tuberculosis in 19th century America. It could also be political, like ethnic movements and disruptions of populations. Or it could be religious trauma: the Reformation, for example, or in earlier cultures, the replacement of polytheistic by monotheistic religions. One important consideration is the move from cremating societies to inhuming ones. So, when people converted either to Christianity or to Islam, their religious change caused them to practice burial. Of course, if you’re used to a situation in which the body is changed into something completely different by burning, and now you have to bury your dead, you might wonder: “Are they really dead or are they actually doing some damage in the grave?”

Were there unexpected things that you uncovered in your research?

I’ve uncovered so many surprises; several in particular stand out. The dangerous dead occur in many past cultures but it’s rather more remarkable to find them in more recent times. For example, in early 18th century Moravia, now the Czech Republic, there was an occurrence which was supported by the bishop of the local cathedral, and it’s an interesting case where, a bit like witchcraft persecution, there’s a feedback loop between popular fears and educated demonological ideas. There are many similarities to witchcraft persecution.

Even more extraordinary are some of the very recent cases, because this practice is not dead. There is an area of southern Romania, west of Bucharest, where these beliefs are still alive. The most recent case that I know about was in 2019 where a grave had a hole in it after it had sunk. In my book I include a photograph from a local Romanian news channel that shows the sunken earth and a hole, which is where people thought that the vampire was coming in and out. The locals dug up the body and staked it through the heart and the local priest recited the liturgy. When the bishop found out, he suspended him. The matter reached court, and, in fact, the case was only settled last February.

The other dramatic case was in 2004, where a farmer had fallen under his horse and died, and then his niece believed that the dead man was preying on her and sapping her energy. A neighbour, fortified with a lot of plum brandy, went to the cemetery, broke into the tomb, cut him open, cut out his heart, burnt it, mixed the ashes with tea, and gave them to the niece to drink, whereupon, of course, she recovered. Meanwhile, another relative had got annoyed and gone to the police. The police raided the cemetery and a journalist filmed the tomb broken open, police cars all round, and the man brandishing a pitchfork saying: “Look, this is the pitchfork I stuck through his heart.”

The interesting thing there, and I think this applies to cultures across time and space, is the reaction of the villagers. Some disapproved, but most said: “What’s the problem? It’s good for the living, it’s good for the dead. It’s what we’ve always done. It just re-establishes the natural balance.” I think this is how people have often viewed it, and there’s an important point in this. When I talk to people about what I’m working on, they question how I can work on such a gruesome, disgusting topic but actually plenty of people work on witchcraft. There’s a long tradition of the study of witchcraft in early modern Europe. So, I respond: “Is it more disgusting to burn living people alive as witches than to burn corpses? Surely ‘killing’ the dead is better than killing the living.” One of my arguments is that this is a relatively harmless outlet for the kind of fear, sorrow, and paranoia that can produce persecution of the living. With a belief in the living dead, there’s usually no persecution of witches, heretics, minority groups, or any people perceived as being ‘other’ in communities.

What role did religion and folklore play in shaping vampire beliefs in various societies?

I think the important question here concerns beliefs surrounding the transition from life to death. In our society death is quite a clear cut and sudden thing but many people have believed that it’s a process, not an event. This includes even in recent times in the British Isles, where the wake was an important time when the body is laid out in the house, and people watch over it. Why do they watch over it? In origin, it’s because it’s a dangerous time: the person has died but their personality and spirit have not yet departed, they’re still in the body. There’s a belief that things could still go wrong and it’s really important that the right rituals are performed from the point of death to the point of burial, or even sometimes beyond the point of burial, for example in societies that exhume the body and put the bones in an ossuary. In many cultures really bad things could happen if something untoward happens during that period. The most dramatic cases are from rural Greece and there’s a wonderful study on this from Euboea in the 1970s by Juliet du Boulay, an anthropologist who worked in these rural communities. It shows how, during the wake, if a creature, particularly a cat, jumps over the body, then it doesn’t matter how good the person was, they become a vampire, and then they’ve got to be extinguished.

There are also particular beliefs about people who have been bad in life. The practice in some rural Greek communities was to bury the body for about 10 years and then exhume the bones and put them in an ossuary during a public event. People would gather to watch and the repute of the family would depend on how clean and white the bones were when they came out. If the bones were clean and white, it means the person’s passed on but if flesh remains, that’s very bad because it means the person hasn’t really moved on and there are still dangerous forces lurking in the body.

The state of incorruption is one of the key things generally and there’s a deep ambiguity here because there are two categories of the ‘special dead’ who are incorrupt: one is vampires and the other is saints. How do you know which is which? There’s a story from 16th century Russia where a parish priest goes into a forest and finds an incorrupt body. He proclaims to have found a saint but when he takes the body back to the church, the locals say, hang on, you should put that body out on the landing just for the time being and don’t take it into the church because it might be a saint or it could be a vampire, and you’ve got to find out which.

Both are categories where special supernatural conditions are preventing the normal dissolution of the body and it won’t be clear if it’s for bad or good reasons until either people start suffering or witnessing miracles.

How does the idea of purgatory relate to all this?

There were many early medieval concepts of purgatory, but the idea of purgatory becomes more developed from the 12th century onwards. It’s interesting that in northern Europe, the 12th century is the point when beliefs in the living dead fade away. In central Europe the beliefs start really getting going in the 15th and 16th centuries but in the British Isles, there’s archaeological evidence from much earlier (the 7th century) and literary evidence from the 11th to 12th centuries. (In fact, William of Newburgh, a chronicler writing in about 1190, says that are so many walking corpses that it’s boring to talk about them!) But only 50 years later, about 1250, it’s almost disappeared from English consciousness. So it may be that the rise and development of the doctrine of purgatory has something to do with that because it provides a midway stage that’s not in the body but somewhere else.

Interestingly, the Orthodox Church did not have a clear concept of purgatory and in Orthodox Greece, in particular, the idea of the incorrupt corpse, almost uniquely, actually becomes embodied in theology. In Greece, there are two kinds of incorrupt corpse: the vrykolakas, which is what we would think of as the vampire that walks around (the church tends to deny its existence or to disapprove of actions against it) and the tympanos, a corpse that is swollen up like a drum and just lies inert and harmless. With the tympanos it’s like the person is in a state of purgatory and often this is because the person is excommunicated and unable to move on.

You suggest that corpse-killing acted as a therapeutic outlet for fear and paranoia; could you explain what you mean by this?

The earliest evidence for this is from a series of enigmatic texts from ancient Mesopotamia, from the 7th century BC, in the context of Ashurbanipal’s empire. The evidence is too fragmentary to be certain, but it may be that those first recorded beliefs are emerging in that context of the violent construction of a new empire. Clearer cases are from 7th century England where we know from archaeology that the corpses are all female and the bodies have been mutilated in a particular way involving turning it over, pulling off the head, and separating the cranium from the jaw. It’s very consistent. It’s clearly ‘killing’ the corpse. This is in the same period when many rich nunneries were being founded and I think the common factor is traditional wise women: powerful women who were magical specialists. These women either went down the Christian route of becoming an Abbess and ruling a nunnery, or remaining a wise woman and then after death, maybe being seen as dangerous. This represents the trauma of losing your religious system, going from the polytheistic system of the Germanic Anglo-Saxons up to the 7th century, and then adopting monotheistic Christianity.

Another time when there seems to be a big eruption of cases is in the 11th or 12th century in Iceland. It may be part of the general changes happening in Europe around and after the year 1000, with some aspects of life becoming more violent, and culture changing rapidly. At that point there’s a complete gender reversal and the living dead are all male. Then it occurs in Lutheran Saxony, in the 1540-60s, and at a time when purgatory has been abolished so the idea that you can intercede for the souls of the dead in purgatory has gone. There you get a very peculiar idea of the ‘chomping dead’: they’re chewing their shrouds, and lying in the grave making chomping noises, which is when you know you have to dig them up because they are spreading plague. The example in very recent times is tuberculosis in America and this seems to go back in origin to Pennsylvanian immigrants from Germany who brought with them this idea of chewing the shroud. There was also a curious idea in New England that the heart of a victim of tuberculosis who has been buried is somehow spreading disease among the living relatives in the same family. So, you have to dig up the corpse, cut out the heart and burn it, and this was widely practised in New England between the 1780s and 1890s. The last known New England vampire exhumation was in Rhode Island in 1892. The last one I know of in any non-Balkan Western society was at Altoona in Pennsylvania in 1949.

How has literature and popular culture shaped our understanding of vampires compared to historical accounts?

When you go back before the 18th century, the boundary between literature and folk story is a bit of a hazy one because the stories that people tell get printed and people believe the stories they read. There’s one case from Moravia, in the 1590s where although the actual pamphlet is lost, there’s enough evidence to suggest there was a popular printed pamphlet for the mass market, which had got a lot of lurid stories that emphasised a sexual element in vampire stories. This is something which you get in later vampire literature as well. When you get into the 18th century, scholars are taking an interest in the stories first as possibly a real phenomenon and then as an illustration of, initially, the devil playing tricks, and then just a phenomenon in humans, a sort of misunderstanding and delusion. In the 1740s, Benedictine Abbot Augustin Calmet published a book mainly based on the Moravian stories that brought it into the framework of scholarly discourse. In the course of the 18th century, we then get the idea of the vampire as a metaphor for exploiters. It’s fascinating if you look at the words of the French revolutionary national anthem: “Let the impure blood of tyrants water our furrows…”; these metaphors are actually coming out of the vampire stories that were now circulating in print. Karl Marx says that capital is like a vampire: it’s dead labour, which preys vampire-like on living labour.

When it comes to fiction, vampire stories became increasingly popular through the nineteenth century, starting with Lord Bryon and Dr Polidori. Sheridan Le Fanu’s story Carmilla was based on a genuine motif, but the most popular of them all, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which is actually very misleading, swept the board and almost blanked out the last traces of genuine beliefs.

What do vampire epidemics reveal about human psychology, particularly in times of crisis?

I think what they show is that one has to have a cause, an explanation. When religious change occurs, it is very traumatic. Likewise, a disease you can’t understand is terrifying. People are powerless so they look for explanations. A folklorist was recorded in the 1970s saying: “Do I believe in vampires? No, I don’t believe in vampires and I’m not sure my ancestors did either, but they just had to find an answer.” We’re all only too familiar with contexts in which traumatised societies have found fictional scapegoats in living groups. Whether it’s an ethnic minority living among you, or the idea that certain people are doing magic, it’s all a fantasy of how living people are doing you harm. This is fantasy also, but it’s fantasy about the dead.

Why do you think vampire myths have remained so enduring, even in today’s world?

Well, of course, they haven’t in the sense that people don’t, in most places, really believe in them now. No educated person, with the exception of the occasional eccentric, has seriously believed in vampires since the mid 18th century. But, of course, where real belief declines so fiction takes over. I think that what we see now with the enduring popularity in fiction, is still the same thing: something which is frightening and lurid but tangible. It’s not like a ghost. You can’t attack a ghost, it’s immaterial, but vampires, like witches, can be tracked, caught, and imprisoned. You can then try them, punish them, behead them, and destroy them. I suppose like any sort of sensational fiction, the enemy needs to be there to be destroyed and you can do that with a vampire.

Do the places that don’t have vampire myths have anything obvious in common?

One thing in Europe is that the places that don’t have the vampire myth do at various times have persecution of heretics and witches. They’re geographically almost mutually exclusive. If you compare England and France in the 12th century, there’s always been a bit of mystery about why you’ve got so much heresy in 12th century France whereas England is almost completely free of heresy, as reported. England does, however, appear to have an epidemic of walking corpses during that period and France does not. I’m sticking my neck out a bit here but it’s almost as if they’re alternatives. I think the answer to that may be that where you don’t get walking corpse or dangerous corpse beliefs you have other beliefs that fulfil the same function.

Can you recommend a book?

There are many books on vampires, some dreadful, some mediocre, and some quite good. I think the best current book on vampires is probably Vampires, Burial, and Death by Paul Barber, which is a very entertaining examination by somebody with a medical background but who is also a folklorist. He proceeds from a physiological point of view: incorruption of the body is a physiological fact and there are certain circumstances which cause corpses not to decay or that produce the illusion that they are still alive.

However, the problem with that line of argument, is that if that if it were just that, then it would be a universal belief. It doesn’t explain why it turns up at some times rather than others. I think what it shows is that incorruption is in the eye of beholder, and you don’t worry about it if you don’t think about this kind of thing but if you are already primed to think about different sorts of supernatural incorruption, then you will notice it. A good example of this is of a saint’s cult in Russia where the Patriarch sends a commission to examine a body to see if is incorrupt. The report comes back that it’s a bit shrivelled, one of the fingers has fallen off, but basically, they can say it just about counts as incorrupt. So, it is a bit in the eye of the beholder.

If you could dispel one major misconception about historical vampire beliefs, what would it be?

In a word: Dracula. Dracula is the major misconception; I think it’s misleading in almost every sense. A lot of people only know about the living dead through the fictional versions. Dracula was the determinative work of fiction on which all subsequent vampire fiction has been based, and it is very misleading indeed. This is mainly because the vampires in which people actually believed are nothing whatsoever like Count Dracula.

Count Dracula is centuries old, he’s a nobleman, he’s wily and resourceful. We see him in action, biting and sucking people. Then the people he bites become vampires. In actual folk belief, that particular belief that people whom vampires bite become vampires is only recorded in one context. It just happens to be the context that Bram Stoker read when researching for writing Dracula. It’s not widespread at all and nor is bloodsucking. The main belief is in the dead doing harm in more subtle ways. Most of the dead are not centuries old, they’re quite recently deceased, and most of them are not aristocratic.