We spoke to Junior Research Fellow in History Dr Shamara Wettimuny about her research.

What first drew you to the study of history?

There was something about the way the study of history revealed historical injustices and the way people resisted and defied power, often state power, that drew me to it as a teenager. Where did notions of justice come from, who was responsible for enforcing it, and who could access justice? Did some individuals or groups have more access to justice than others? These were questions I encountered when learning about the past, that were also helping me make sense of the present, at a time when I was becoming more conscious of the political world around me. So, there’s that, but also doing history is so much fun! There’s never a dull day at the office!

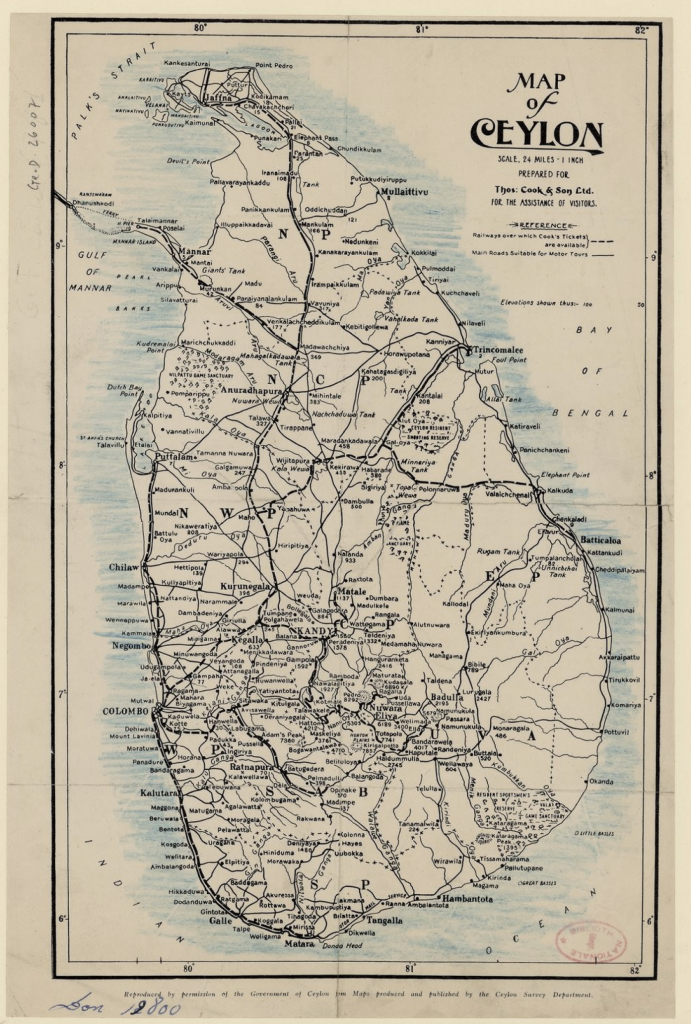

Your doctoral research reopened a neglected chapter in Sri Lankan history. What did you feel was missing from the narratives?

I was conscious that popular narratives about the ‘1915 riots’ seem to have turned events upside down. Victims were portrayed as villains while perpetrators were absolved of any responsibility for violence. What was missing in all these narratives were the voices of the victims themselves – who were there, what was their experience, and why were they silent? I am not the first person to work on this particular episode of ethno-religious violence so I had important research to build on, but I also approached it through a combination of vistas that, methodologically, had not been attempted before. I deliberately recentred the experience of women, who were marginalised into a mere statistic: ‘four women raped’. By trawling the archives for fragments of their experience, I was able to tell a more holistic and nuanced narrative of ethno-religious violence in colonial Sri Lanka.

By trawling the archives for fragments of their [marginalised] experience, I was able to tell a more holistic and nuanced narrative of ethno-religious violence in colonial Sri Lanka.

You write about cycles of intolerance and victimisation. What did you find most striking about the patterns?

The entire process of going into the archives and digging up forgotten histories was useful in checking my own preconceived notions. It turned out that there were no fixed actors who were either ‘good’ or ‘bad’, sympathetic or unsympathetic. Instead, those who were intolerant of others could radicalise certain people to the point where there was blowback: aggressors could in turn provoke a violent reaction, and become victims themselves. This pattern, which emerged at the turn of the twentieth century, played out with cruel familiarity in the past decade in Sri Lanka.

Your recent article ‘The Jews of Ceylon’: Antisemitism, prejudice, and the Moors of Ceylon explores how antisemitic language and stereotypes were used in colonial Ceylon to target a non-Jewish minority. Why do you think this proved so effective in shaping how Moors were perceived and what are the lasting effects of this?

The British introduced the epithet ‘the Jews of Ceylon’ to refer to Moors, a Muslim minority community that occupied a socioeconomic niche on the island as traders, including as gem merchants and hawkers of clothes. Though antisemitic tropes were not repurposed into the vernacular, some Sinhalese nationalists – who pitted themselves against Moors – deployed the language of ‘Shylockian Jews’ among other stereotypes when trying to justify, to the British coloniser, their violence against the Moors. Curiously, Sinhala-language newspapers from the late nineteenth century carried campaigns calling to boycott Moor shops and ‘buy Sinhalese’, which are comparable to campaigns to boycott Jewish establishments in early 20th century Germany and Poland, for example. Islamophobia and antisemitism then shared features of religious and racial prejudice that were often deeply connected to economics and market control.

Islamophobia and antisemitism then shared features of religious and racial prejudice that were often deeply connected to economics and market control.

How did you approach working with sources that contain explicit prejudice or hate speech?

This is a really important question and one that I still grapple with. Am I recreating or re-inscribing harms by putting on paper some of the dehumanising and deeply prejudicial comments I come across in the archive? I have taken the position that it is necessary to do so, with care, for the sake of academic research and analysis. Of course, I don’t do it wantonly or simply to shock my audiences for the sake of it. Instead, I refer to certain claims, that count today as hate speech, to highlight the longevity of certain prejudices and to make sense of insecurities and grievances, whether real or perceived, held by those responsible for such speech. A lot of the hate speech I look at from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was published widely in the periodical press. Analysing such speech gives us a sense of the cultural stereotyping that was taking place, what we might today refer to as ‘conspiracy theories’ and fear-mongering, and offers an insight into the undercurrents of violence that eventually erupted on an island-wide scale.

Your research is both global and local. How do you navigate a balance, especially when dealing with colonial legacies and present-day realities?

Colonial legacies still percolate in present-day Sri Lanka and help explain structural injustices and long-term inequalities, the consequences of which we still deal with today. At the same time, the post-colonial ethno-nationalist state is its own beast, especially in terms of enabling and perpetuating racial and religious discrimination of certain communities. When it comes to history writing, the chasm between priorities in ‘the West’ and those of the global South are also clear. Yes, there is a need to decolonise education and knowledge, but in places like India that discourse has somewhat justified a state-led erasure of aspects of its Islamic past. Scholars (of and) from the Global South are doing a really important job of managing these often competing priorities, to keep up with new trends in history writing for instance while also meeting the challenges of state power and its influence on the making of history in the present.

Having worked in both academia and policy research with Verité in Colombo, how do you see those two worlds influencing each other?

My experience in policy research in between academia, I feel, was especially transformative for me. I worked on contemporary anti-Muslim and anti-Christian violence and discrimination at Verité, and it was through that research that I decided to return to history and examine the roots of ethno-religious violence in Sri Lanka. Meanwhile, strong policymaking is dependent on serious research that has been conducted over many years (as opposed to only short cycle research projects, in places like Sri Lanka, that are donor funded and thus determined by donor priorities) and will to some extent come out of the academy. I would hope that my work on the long-term roots of communal conflict in Sri Lanka can advance both historical debates and contemporary peace-building efforts, especially with the recognition that what is happening today is not new. Instead, its origins are over a century old.

What is happening today is not new.

Through your organisation Itihas, you’re working on history education reform. Why is that important in Sri Lanka today and what do you hope to change?

In 2022, I started a non-profit organisation called Itihas to work on non-state history education initiatives at a time when mass public protests broke out in Sri Lanka against the ruling regime. The name Itihas is a combination of the words for history, Ithihaasa in Sinhala, and Ithihaasam in Tamil, with the Sinhala word for ideas, ‘adahas’ –and is intended to represent a space for new ideas about history. Currently, Sri Lanka’s state-school history syllabus does not meaningfully address our post-Independence history, aside from brief discussions on constitutional reform. Significantly, there is no discussion of the root causes of our civil war which lasted three decades, nor any exploration of the two Marxist insurgencies that took place against the state before being put down with grave violence in the 1970s and 1980s. Despite repeated efforts by history professionals to drive reform, there is limited political and bureaucratic will to introduce change. Given the deficient syllabus and marginal space for state reform, Itihas works with school teachers and junior university lecturers from across the island, to help them think about the silences and omissions in syllabi, and innovative ways to address them.

What do you enjoy about being a Junior Research Fellow at Queen’s?

The space created for JRFs to research, think, write and publish at Queen’s is truly incredible. I am so thrilled to be here and take advantage of everything that is available to us. One of the most enjoyable parts has been getting to know the rest of the Early Career Researcher community at Queen’s, where everyone is so generous with sharing time and ideas, and forming a support network. Similarly, the community of current and retired Fellows has been wonderful to get to know, spend time with, and learn from. I will leave Queen’s with very fond memories!