Lauren Ward, Assistant Librarian

When you work in a place with a collection of around 120,000 rare books, it’s impossible not to pick up a thing or two about them. However, books created in the hand-press period are complex objects. There are ever-growing avenues of scholarship emerging on their creation and use, making piecemeal knowledge unhelpful when answering enquiries or cataloguing new acquisitions. So, encouraged by the College’s interest in facilitating staff training and CPD, I (Lauren, Assistant Librarian) and Sarah (Deputy Librarian) attended London Rare Book School earlier in the long vacation. The week-long summer school allowed us to spend focussed time learning with experts, from the ground up, how the objects filling the shelves of the Upper Library and the underground vault were created.

Over thirteen seminars we learned ‘close looking’ techniques – quite literally looking at books carefully for material clues – as well as terminology for what we found, and got practical experience of typesetting and printing.

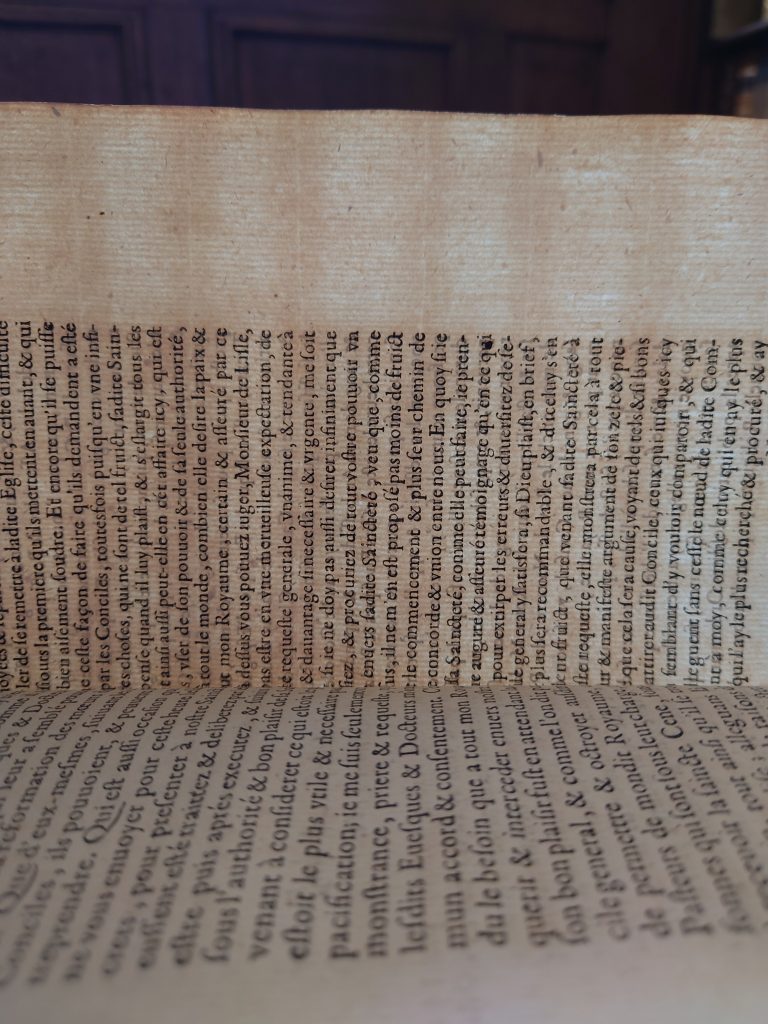

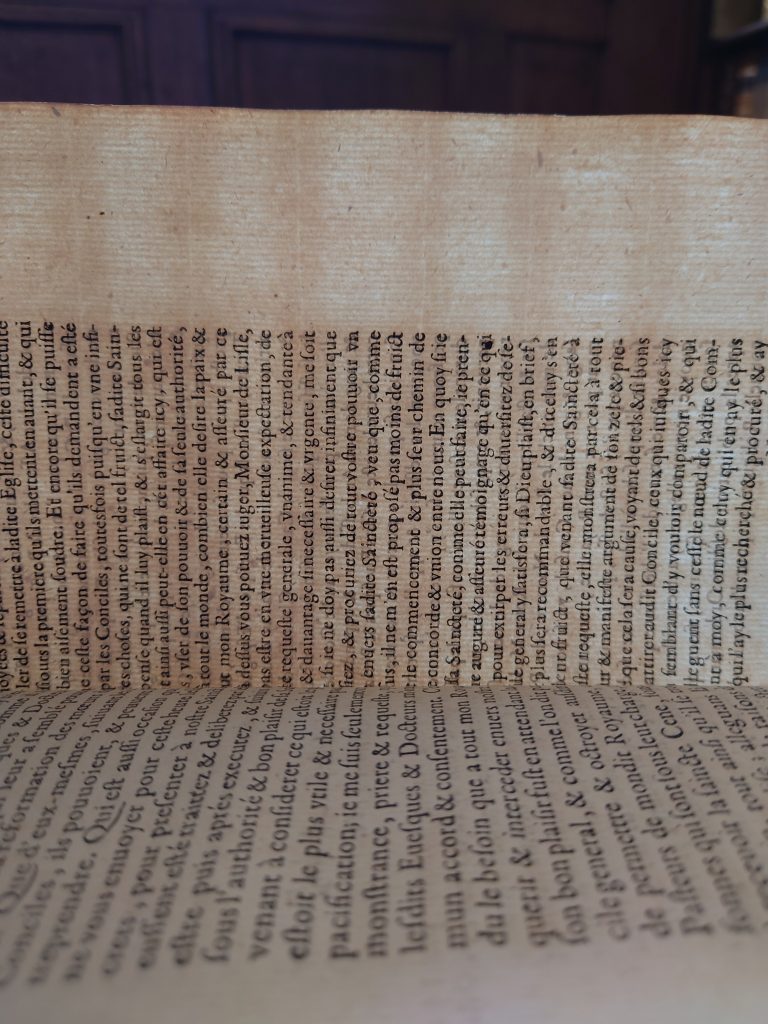

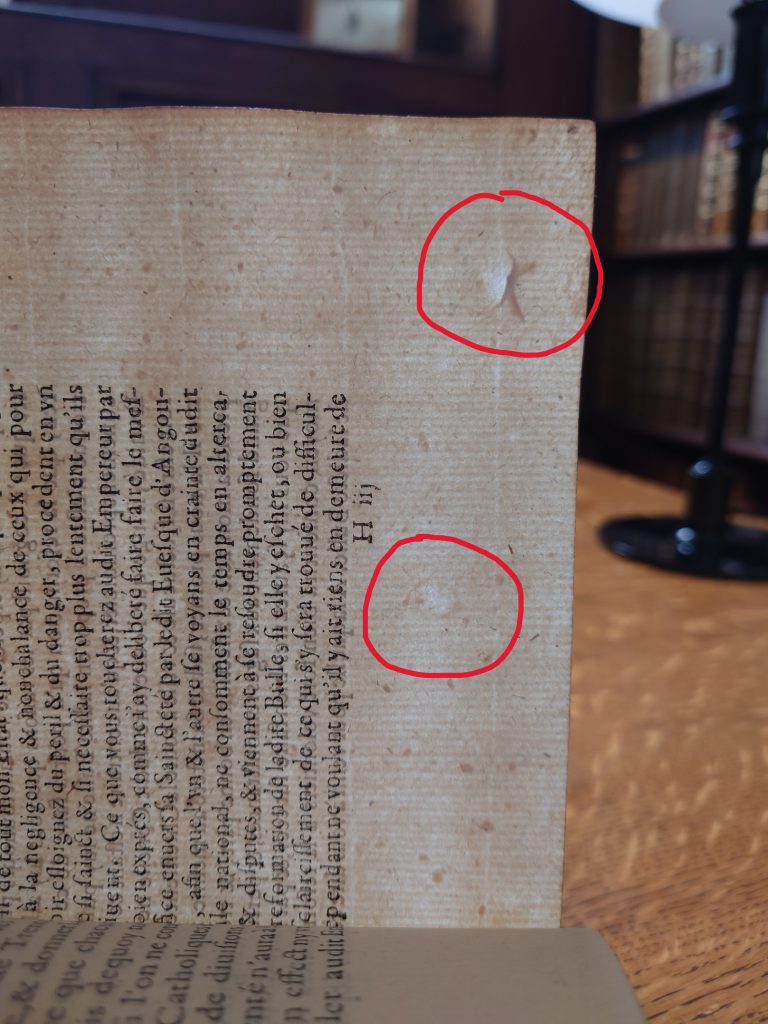

We started with paper – not something I had given a great deal of thought to before, but something without which printed books wouldn’t exist, as parchment (the animal skin used to create manuscripts) doesn’t pair well with the printing press. Our seminar emphasised the physicality of papermaking and the traces of this effort that are left behind. From the slight thickening of the paper around the chain lines, made by the suction created when a paper mould was heaved out of the vat, to vatman’s tears, there are signs of the (literal) sweat that went into creating paper if you know where to look. Even the very beginning of the process, gathering the rags required to break down into the mush that became paper, was extremely labour intensive. Interestingly, part of the reason paper-making didn’t really get going in England until the 1800s was partially due to the lack of available rags in the right quality and fabrics – English people often wore wool, which can’t be used for paper, rather than linen.

Vatman’s tears are signs of the (literal) sweat that went into creating paper.

Please click on the images for the captions.

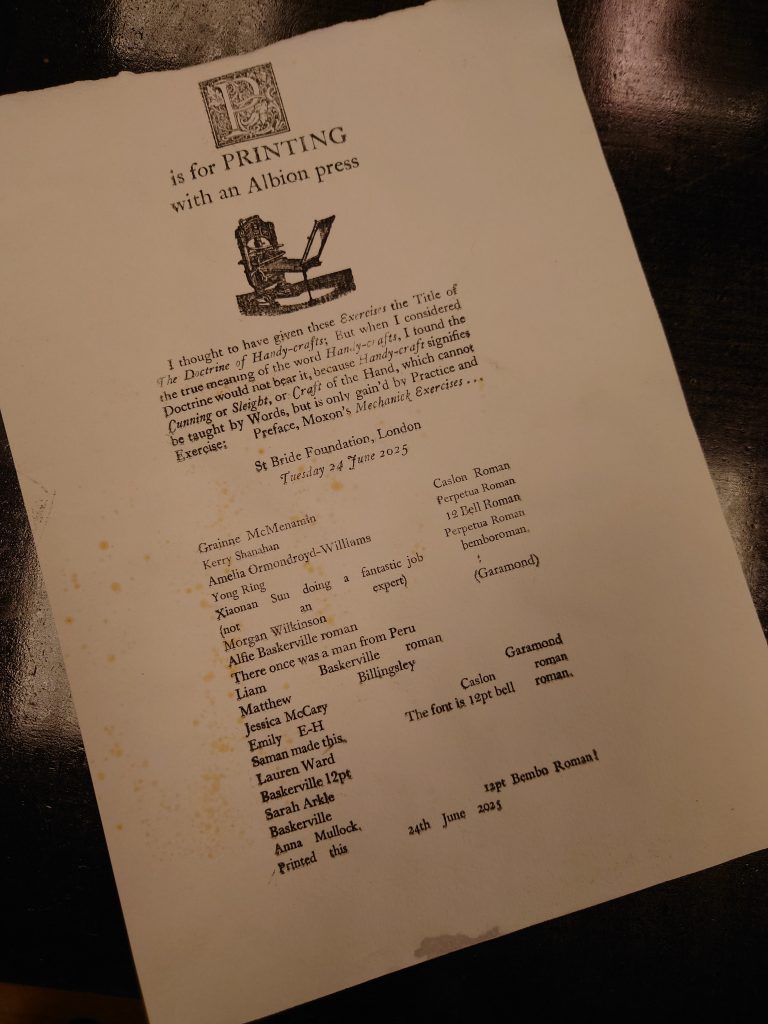

On day two we visited the St Bride Foundation for a workshop on typesetting and printing. Our tutor Richard Lawrence (who can be found very nearby operating the Bodleian’s bibliographical press) was incredibly knowledgeable and did a great job of breaking down some of the reverence we can feel when approaching old books. They are amazing objects to us now, but the people who produced them were businesspeople trying to turn a profit, or maybe just make enough to go to the pub.

In the hand-press period, typed and blank spaces were created by physical means. Each piece of type or ‘sort’ had to be picked from the case by a compositor and placed upside-down into a composing stick. Incidentally, the phrase ‘upper case’ referring to capital letters comes from the position of these sorts in the compositor’s type case, as they were often above the ‘lower case’ letters. Composed lines of type were then transferred into a chase (metal frame) which was locked into place using pieces of wood and expandable ‘quoins’ to create tension, inked, and put on the press bed. The final page layout is called a ‘forme’. We tried our hands at setting lines of type and operating the printing press – see below – to variable results. The experience gave us a small taste of the demanding work of the printing shop; I’ll never chuckle at an early modern typo again.

I’ll never chuckle at an early modern typo again.

Please click on the images for the captions.

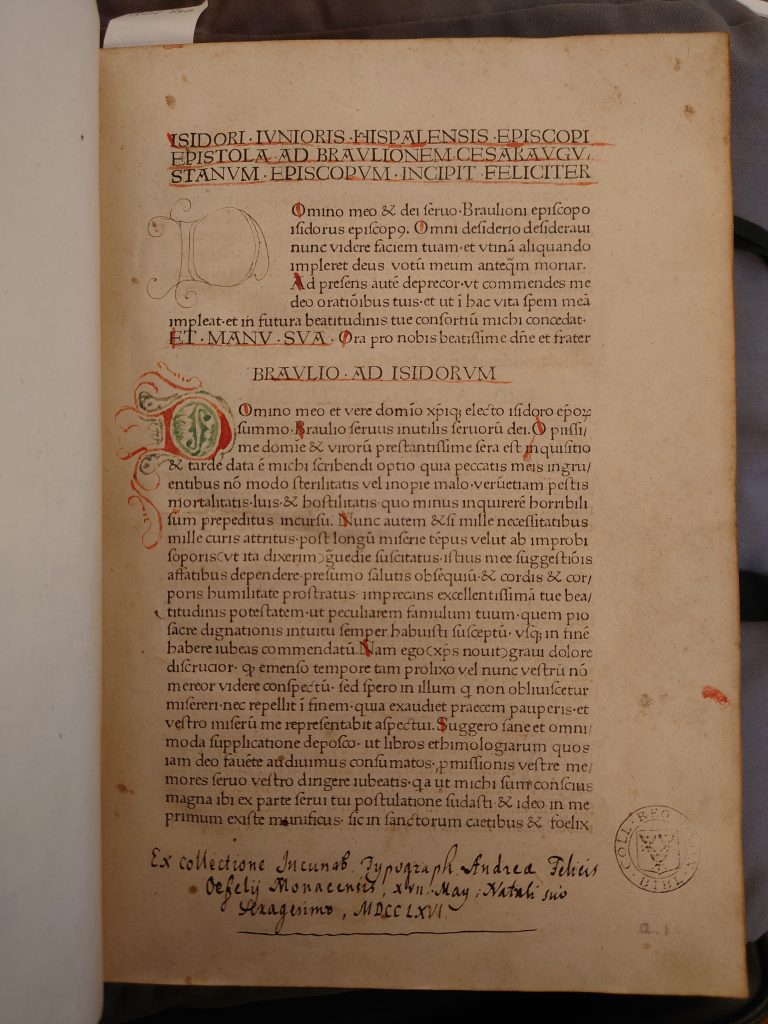

In the following days we had seminars on the crossover between manuscript and print culture, allowing us to see how the two influenced each other before diverging, learned how to write a bibliographic collation formula, and how to identify different parts of a book’s binding structure, including the types of animal leather that might be used.

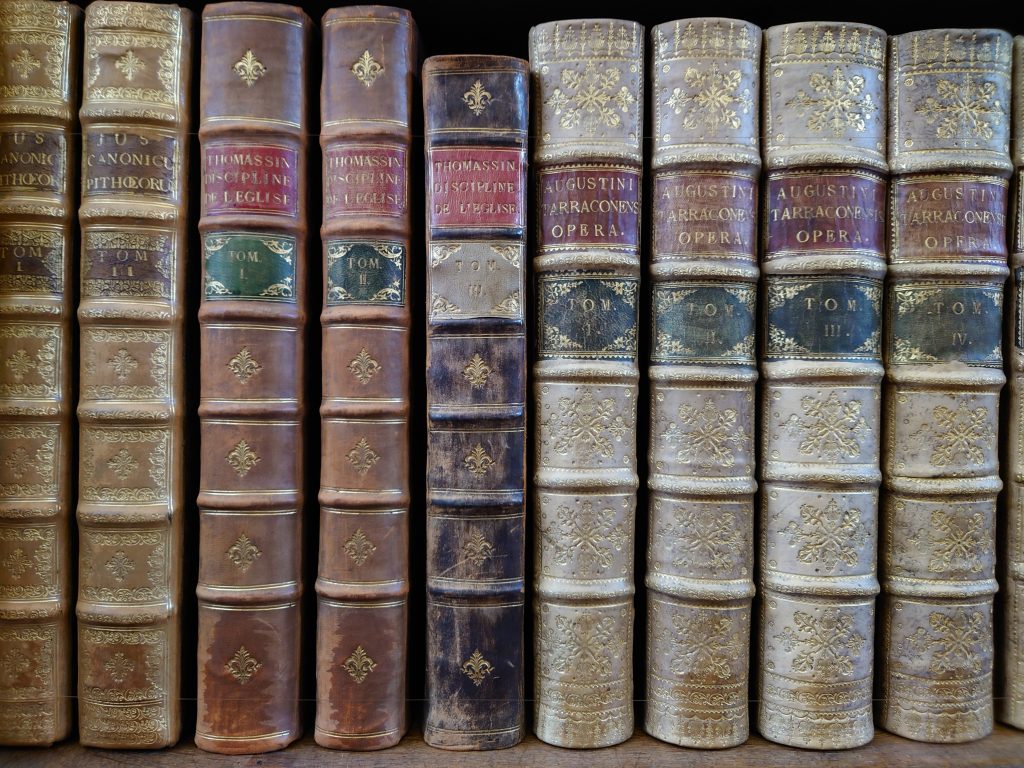

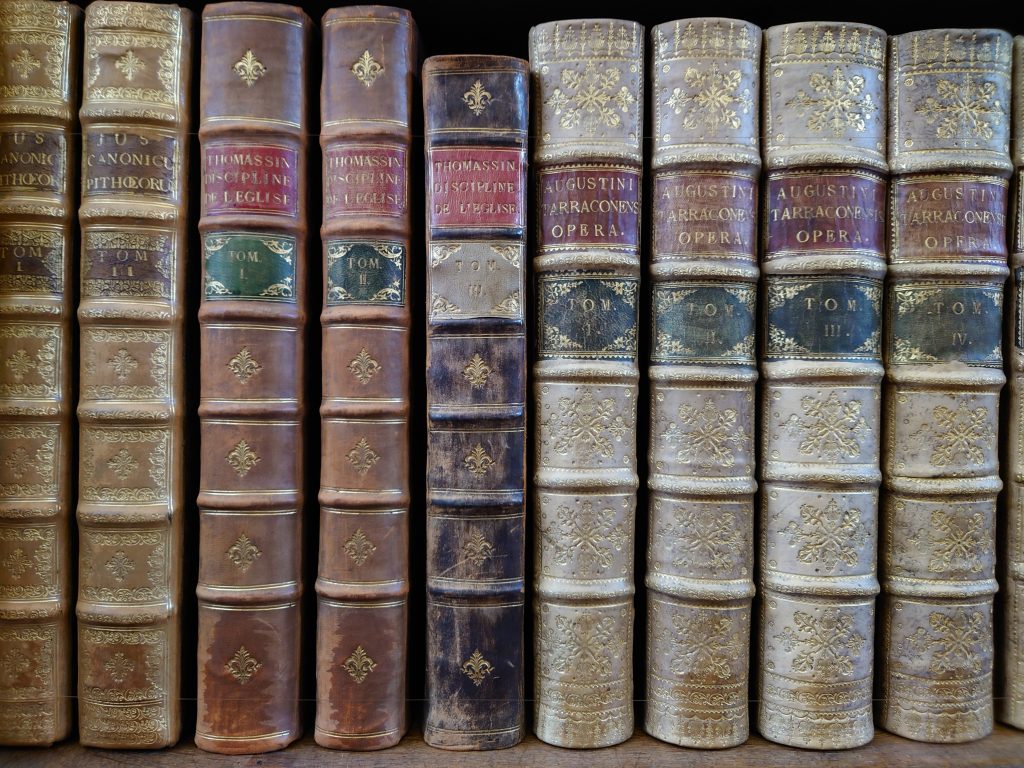

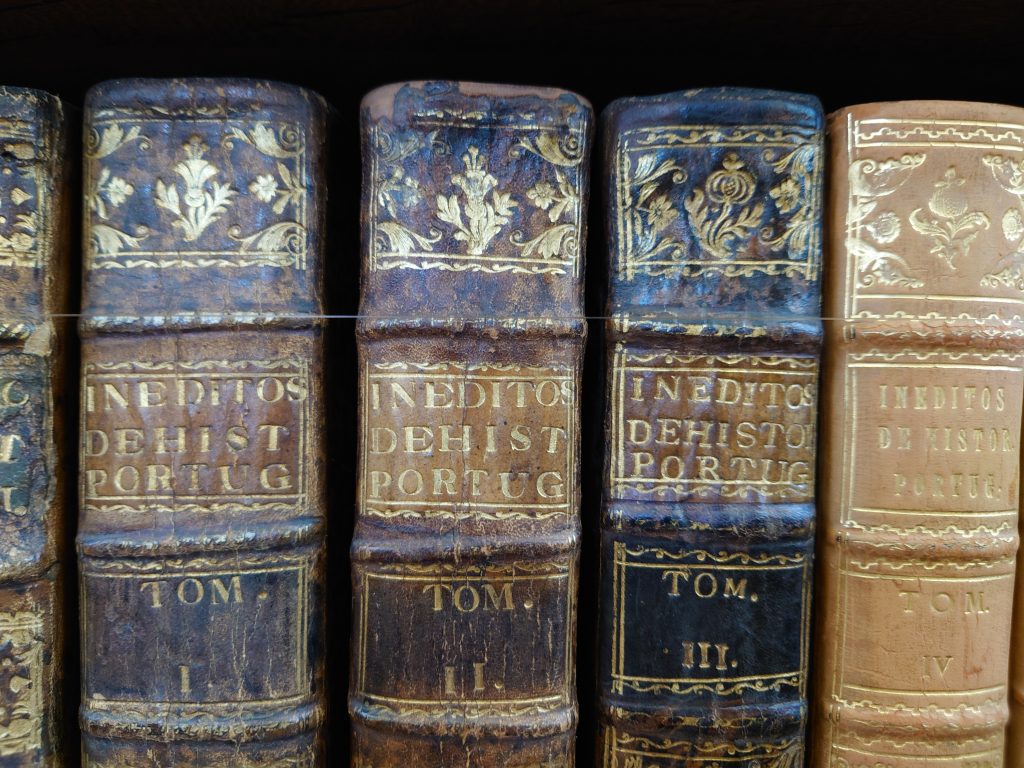

This seminar, led by renowned provenance and binding expert David Pearson, proved particularly fascinating as our group’s perceptions of bookbinding as a fine art were challenged. Bookbinders were thought to be very lowly in the early modern period, to the extent that many binders’ names go unrecorded as they weren’t considered important. Apparently, they were also ‘notorious drunks’ (this theme cropped up again and again – it seems the entirety of the book trade just really wanted to be in the pub), so perhaps that had something to do with it. Still, we were able to admire examples of bindings from the very fine to the commonplace and, with our newly sharpened eyes, could spot the small mistakes or ‘good enough’ pieces of decoration. Binderies were businesses after all and leather was expensive; anything but the most catastrophic mistake would have to stay as it was.

Please click on the images for the captions.

The entire week really drove home the amount of physical labour involved in the making of books. From the picking of the rags for paper-making to the force required to get type and illustrations to print evenly, every book from the hand-press period represents a huge quantity of human effort. It also demystified lots of quirks of old books (those alphanumeric codes at the bottom of the pages aren’t unusual numbering, they’re page signatures), and made us realise that most oddities found in them are probably the result of an effort to save time, or money, or both. Most importantly, we both now feel more confident interpreting and researching books from the hand-press period, and have been able to put our new skills to use on some recent acquisitions for the collection.

![A book page from 1613 with the title 'Double books to be exchanged according to [the] pleasure of...'](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Double-Books-cropped.png)