Queen’s and the Decadents: Exhibition in the New Library

Felix Taylor, Library Assistant

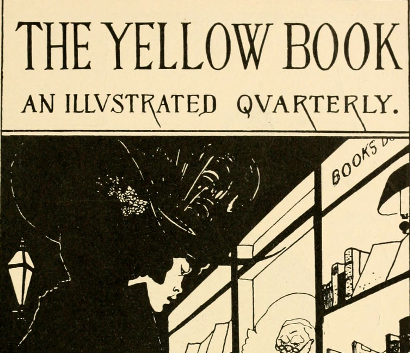

The word ‘decadence’ is used these days to mean anything self-indulgent or hedonistic (rich foods, luxurious clothing, or sex) but when applied to the final decades of the nineteenth century it refers to a set of themes in art and literature that were viewed by conservative critics as a sign of cultural degeneration and moral decline. Emerging in France in the work of poets of the Symbolist and Aesthetic movements, Decadence soon spread to Britain where it became synonymous with familiar figures like Oscar Wilde and the illustrator Aubrey Beardsley. Periodicals such as The Yellow Book and The Savoy sprang up to cater to this evolving avant-garde. Only when Wilde was sentenced to two years’ hard labour for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895 did the bubble finally burst and decadent art and literature begin to be shunned by the wider public.

Only when Wilde was sentenced to two years’ hard labour for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895 did the bubble finally burst and decadent art and literature began to be shunned by the wider public.

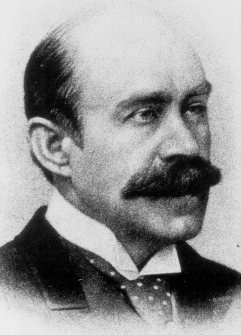

While close neighbour Magdalen College can boast the likes of Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas as alumni, The Queen’s College has its own links to the Decadent movement. Currently in the New Library there is on display a small exhibition of books relating to two of the College’s Old Members, Walter Pater (1839-1894) and Ernest Dowson (1867-1900). They matriculated 30 years apart but left their mark on the period known as the Yellow Nineties in important ways. Pater is now considered one of the founding theorists of aestheticism whose essays set the imaginations of Wilde and others alight, while Dowson was perhaps the Decadent Poet par excellence. After his death from tuberculosis at the turn of the century, he became enshrined as part of W. B. Yeats’s ‘Tragic Generation’ – the pantheon of writers and artists who lived ‘lives of such disorder’ and consequently did not survive into the 1900s. His reputation as a poet is often overshadowed by his infatuation for the young Adelaide Foltinowicz, the young daughter of a Polish restauranteur whom he met in 1889 when she was just 11.

The Queen’s College has its own links to the Decadent movement.

As a commoner at Queen’s, Walter Pater held an ‘exhibition’ (scholarship) for three years, provided by the King’s School, Canterbury. He took his B.A. in December 1862, after which he tried, and failed, to take Holy Orders. He never strayed far from the College during this period, and may have taken rooms in Grove Street (now Magpie Lane) where he worked as a private tutor. He would certainly have known George Augustus Simcox, a newly-appointed classics Fellow at Queen’s and a writer who was deeply influenced by current Romantic literature (see previous blog post on Simcox). Soon Pater was elected Fellow of Brasenose College in 1864. Here he began to write essays, particularly on poetry (his first was on Coleridge), and his literary voice took shape. From 1867 he penned a series of articles for The Westminster Review which would be collected as Studies of the History of the Renaissance in 1873. Pater saw the Renaissance as a period of broad enlightenment beyond merely the fifteenth-century revival of classical antiquity. It was an ‘outbreak of the human spirit’ which overcame the constrictions of medieval religion.[1]

In 1877 the 22-year-old Oscar Wilde, then in his third year at Magdalen, sent Pater an article he had just had published in the Dublin University Magazine. Pater was impressed – ‘It shows that you possess some beautiful, and for your age quite exceptionally cultivated, tastes, and a considerable knowledge also of many beautiful things’ – and the two began to meet regularly. Wilde was already cultivating his pose of arch-aesthete and looked up to Pater, having been enraptured by Studies in the History of the Renaissance in his first year. Sections of it are spoken aloud by Dorian Gray, and by the time Wilde wrote De Profundis from Reading Gaol in 1897 he claimed to know much of it by heart.[2] The book informed Wilde’s personal creeds of beauty, imagination, and becoming ‘drunk with life’. A close family friend of the Wildes was Queen’s Fellow A. H. Sayce, making it possible that Wilde was a regular visitor to Queen’s during his time at Oxford.

Pater was still an influence in Oxford when, a decade later, Ernest Dowson entered Queen’s in 1886. Dowson had come from a well-to-do middle-class family, his father the owner of a dry dock in Limehouse. They had travelled widely when Dowson was young, to Europe, where little Ernest was introduced to important literary figures such as Robert Louis Stevenson (with whom he played dominoes) and French writer Guy de Maupassant. He did not go to school, so it was down to his father’s ability as an educator that he passed the entrance examinations to Oxford. At Queen’s, his rooms were at the top of Staircase 5, Back Quad, sparsely decorated, and seemed to visitors as if he was always on the verge of moving out.[3] Fellow E. M. Walker (later Provost 1930-33) remembered how Dowson appeared ill ‘from the time he arrived until he went down’, and other contemporaries noted how he stood out from the other students. He was better read than his peers, and while at Queen’s obsessed over the poetry of Charles Baudelaire, Edgar Allan Poe, and the Jacobian dramatists.

Like Pater, Dowson lived on Grove Street, moving into no. 5 in Michaelmas 1887. Friends claim that this marked a period of depression for Dowson. His father’s business was suffering, and he may have been made aware that his studies were now a financial strain on the family. Whiskey became his drink of choice (not unusual for an undergraduate). Dowson’s time at Queen’s ended abruptly when in March 1888 he sat for Honours Moderations, and after completing only part of them, decided he would give it all up. At the end of Hilary term Dowson left Queen’s and settled for a time at his parents’ house in Woodford, East London. His Oxford career was brief, and though it is where he began to nurture his literary abilities, the University does not seem to have left a lasting impression. As he wrote to Arthur Moore in February 1890:

I found myself at Oxford (naturalich) at about 11.40PM. & stayed with Swanton. I came back to-day – finding it supremely triste: did not go near Queen’s at all – nowhere in fact. A place which is born again every 3 years has its drawbacks.[5]

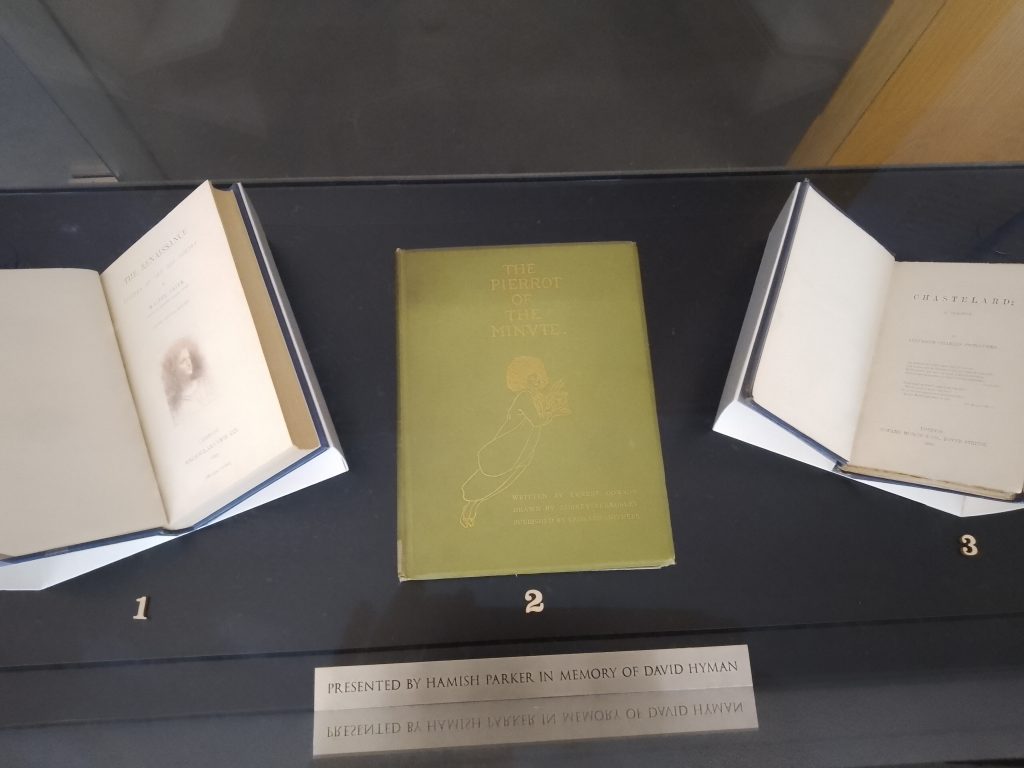

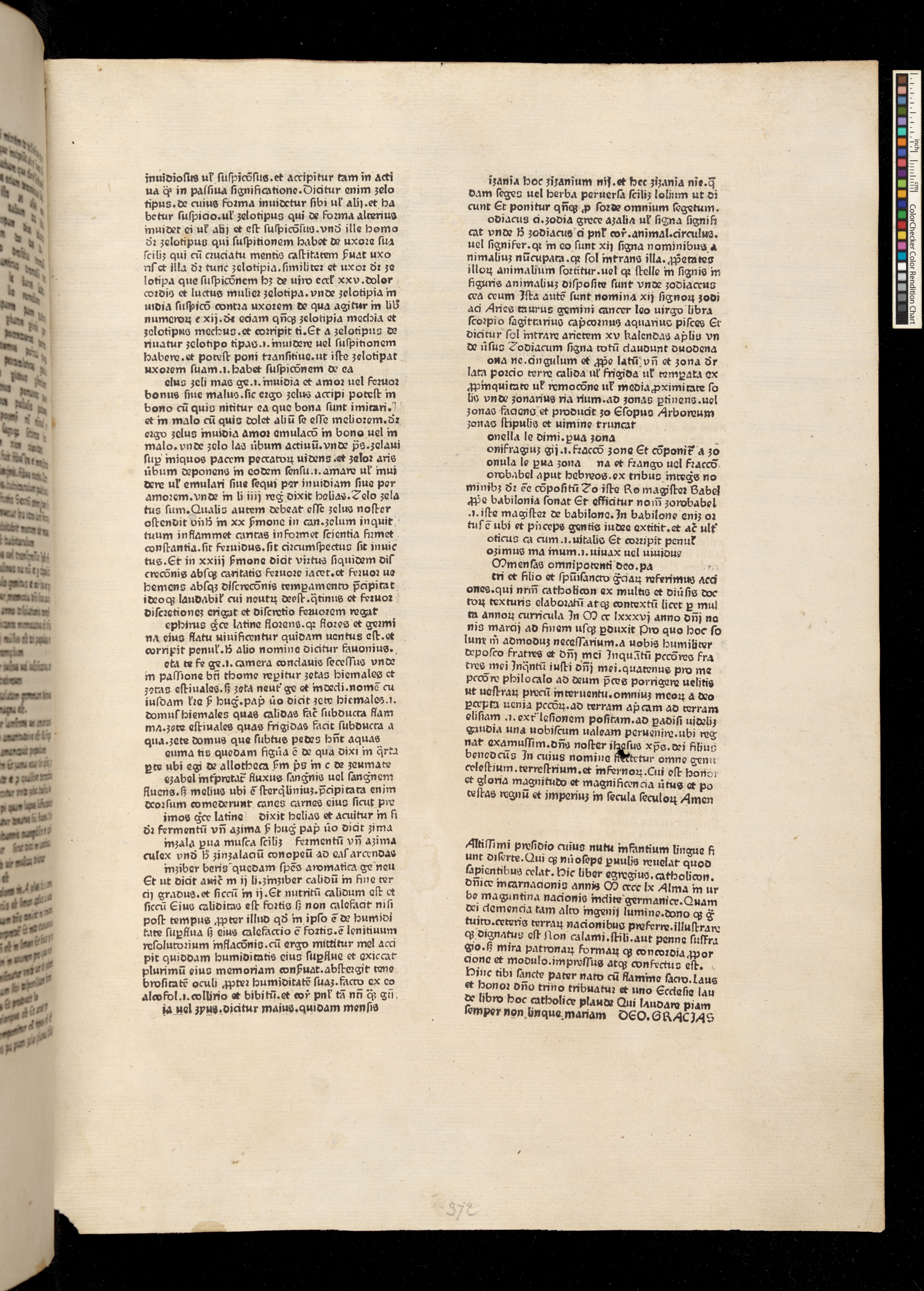

The New Library exhibition case displays Pater’s The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry from 1877, given to the library by J. R. Magrath, alongside Dowson’s The Pierrot of the Minute: A Dramatic Phantasy in One Act with illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley, published in a limited edition in 1897. Also on display is Chastelard (1865) by Algernon Charles Swinburne. Swinburne’s poetry caused a stir in the 1860s, full of pagan themes and same-sex love, and went on to inspire a generation of decadent writers. It was apparently due to Dowson that the Library first added Swinburne to its collection.[6]

[1] Walter Pater, Studies in the History of the Renaissance (London: Macmillan, 1873), p. xi.

[2] Richard Ellman, Oscar Wilde (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1987), p. 46.

[3] Mark Longaker, Ernest Dowson (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1968), p. 26.

[4] The Letters of Ernest Dowson, eds. Desmond Flower and Henry Maas (London: Cassell, 1967), p. 10.

[5] Dowson to Arthur Moore (23 February 1890). Letters, p. 139.

[6] Letters, p. 9.

![A book page from 1613 with the title 'Double books to be exchanged according to [the] pleasure of...'](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Double-Books-cropped.png)