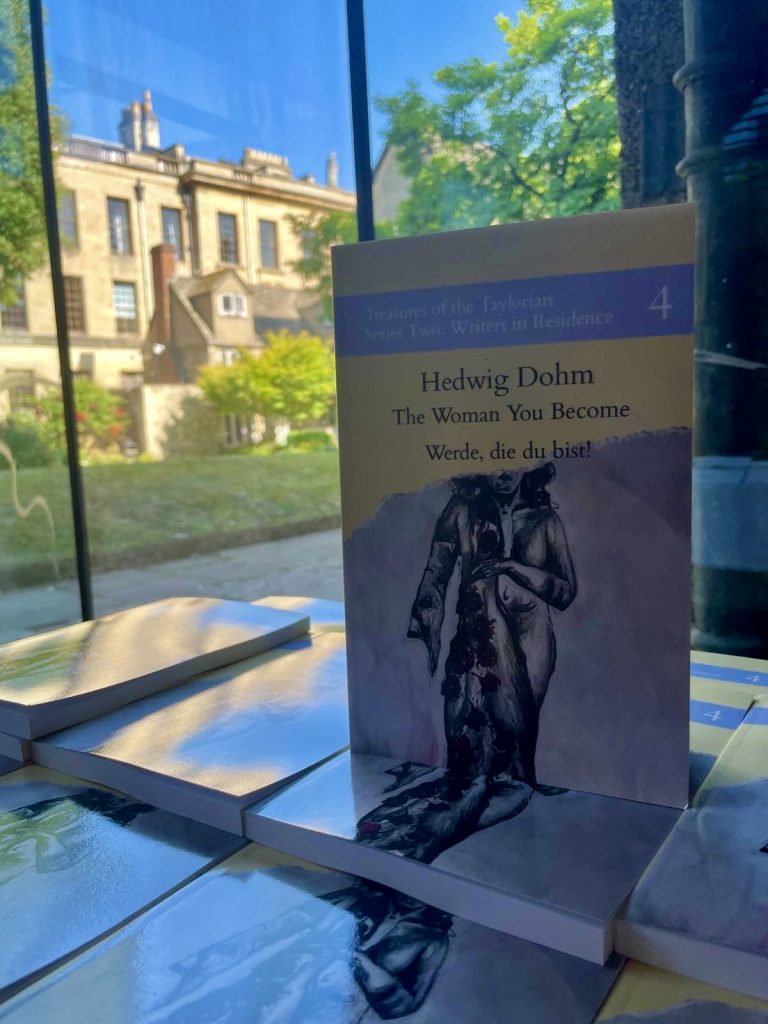

In Hilary and Trinity terms of 2025, the second-year students in German worked on a collaborative translation of Hedwig Dohm’s novella Werde, die du bist! (1895), edited by their tutor Marie Martine.

It was published as a bilingual edition by the Taylor Editions as part of its Writers in Residence series. More information on the Taylor Editions and the translation. We asked them about the process.

Questions for Marie

What drew you to this particular nineteenth-century text?

I discovered this text during my DPhil on women’s writing at the end of the nineteenth century in Germany, France, and Norway. Hedwig Dohm (1831-1919) is a fascinating figure: despite having received a limited education, she actively participated in Berlin’s intellectual circles and eventually established herself as a prominent essayist. Her feminist essays respond to contemporary misogynistic discourses that argued that women cannot participate in the public sphere without putting themselves and society in danger.

This text is interesting not only for its political resonance but also for its poetic quality.

Her fiction adopts a more pessimistic stance, describing the constrained lives of contemporary women struggling to liberate themselves from social expectations. Her novella Werde, die du bist! (which we translated as ‘The Woman You Become’) was published in 1895 and tells the story of Agnes Schmidt, a widow who tries to find herself after a life of sacrifice as a wife and mother. This text is interesting not only for its political resonance but also for its poetic quality. Agnes writes about her connection to the natural world and her existential interrogations in a beautiful and sometimes complex prose. Dohm’s fictional writing has only been recently rediscovered by feminist scholars, but it has its place among other canonical nineteenth-century texts. It was an honour to edit a collaborative translation of this text aiming to give it a contemporary resonance and to make it accessible to English-speaking readers.

What’s unique about translating literature in a collaborative environment?

Translation is often perceived as a solitary activity, especially within the university context where students typically complete their assignments independently and are assessed through individual exams. But translation can also be a dialogue: a dialogue across time between a writer and a translator, a dialogue across cultures and languages, and it can also be a dialogue among translators. Collaboration sparks creativity: when a student was stuck on a sentence, a paragraph, they could always count on the discussions in class to come up with creative solutions together. Collaboration can also carry a political dimension: as we worked together to convey Dohm’s political message, we reflected on what it means to collaborate on a translation. At times, our discussions flowed smoothly; at others, they became more animated, as students passionately defended their interpretations. Yet the shared goal remained consistent: to reach a compromise that reflected the collective voice of the group and do justice to Dohm’s own feminist project.

Collaboration sparks creativity.

Were there moments where the students’ perspectives changed the way you saw the text?

Translating this text with a group of four brilliant students reminded me, again and again, of the poetic quality of this text. In my research, I mostly focus on Dohm’s political message and her dialogue with contemporary discourses on womanhood. But witnessing how the students tried to convey the fluidity and the beauty of Dohm’s descriptions was a reminder of Dohm’s unique style and how she plays with language to convey her message. We hope to have conveyed the evocative power of Dohm’s style through our creative translation.

Questions for the student translators

What does it mean to have the work published in the Taylor Editions Writers in Residence series and go into the Queen’s College library?

Emily Dicker: When I first applied to Oxford, I would never have dreamed that I’d be a published author by the end of second year! It’s been amazing to work on this project over the last two terms and see how translation, which is often seen to be a somewhat mechanical exercise confined to the classroom, can be brought to life in an extremely creative process with very concrete results. We’re very lucky that the Taylor Editions’ Writers in Residence series makes this possible and, although I still can’t quite get my head around it, it’s going to be so exciting to see our names among the authors we study in the Queen’s library!

When I first applied to Oxford, I would never have dreamed that I’d be a published author by the end of second year!

How do you hope readers, or future students, will engage with this edition?

Emily Dicker: Predominantly, I hope it will serve as a huge source of inspiration for the fun which can be had by doing a Modern Languages degree at Oxford. But I also think it’s amazing to have a bilingual copy of this incredible text so that it becomes more accessible to all readers, and not only those who understand German. It would be amazing if, as a result, readers gained a new favourite book which would otherwise have been inaccessible to them or even if, upon reading the German and English in parallel, they were inspired to learn a bit of the language for themselves.

I hope it will serve as a huge source of inspiration for the fun which can be had by doing a Modern Languages degree at Oxford.

What did you learn from the translation process?

Lia Neill: The process of trying to translate an entire short story – rather than the shorter excerpts which we usually translate in classes or exams – raised lots of different challenges. It was interesting to keep track of repeated descriptions and motifs across the text, and think about how we wanted to translate these in each instance – could we use the same word to mimic the repetition of the original, or did it make more sense to adapt our previous translation to the new context? The editing process was also an exciting new opportunity – I really enjoyed reading back our previous work, reflecting on the decisions we made and scrutinising our translation to see how it could be improved, both as a standalone piece of English prose and in relation to Dohm’s original German.

What was it like working so closely with one another, and with your lecturer, on a creative academic project?

Lia Neill: Collaborating on a translation has been a really rewarding experience. It was great to hear what everyone else had been working on each week and come up with creative solutions together – I can’t imagine completing a literary translation without this group support! The opportunity to work more collaboratively has definitely brought us closer as a cohort, on an academic as well as a personal level – I feel like I now have a stronger awareness of each of our individual “voices” as writers and translators. It was really nice to read the final short story as a whole and see where each of our voices come through, and to remember the various discussions and (sometimes heated) debates we had along the way!