Dr Matthew Shaw, Librarian

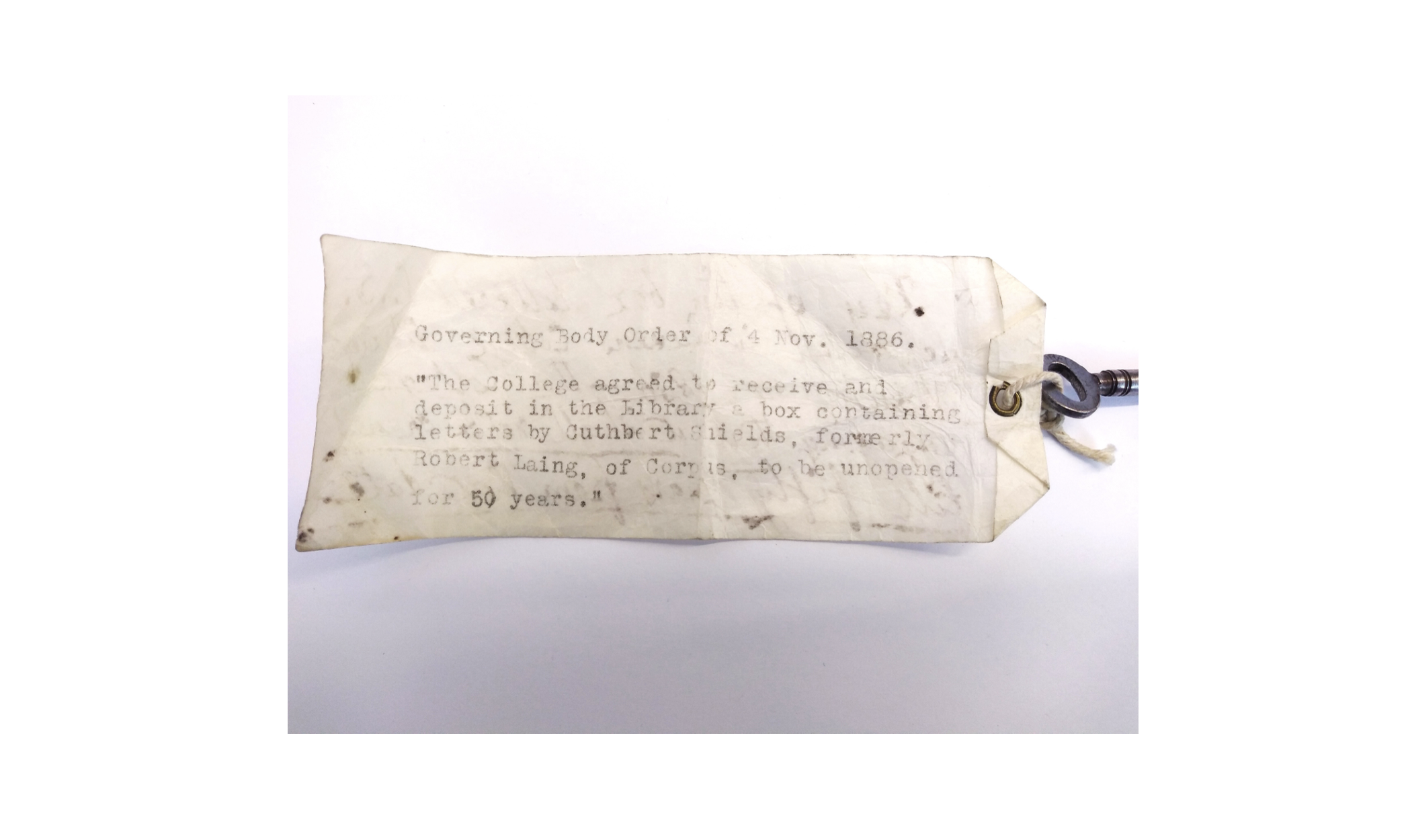

Winter as a season lends itself to poetry. For the novelist and poet Thomas Hardy (1840-1928), it offered a valedictory framing for his final collection, Winter Words in Various Moods and Metres. Published posthumously in 1928 by Macmillan & Co, his estate bequeathed the manuscript to the College, where it is now held in the Library vault.

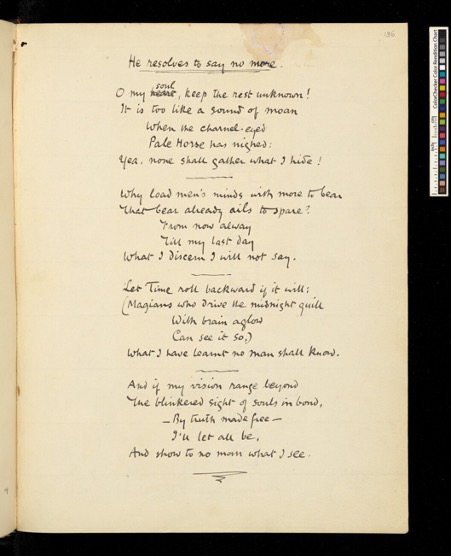

He Resolves to Say No More, Thomas Hardy

Hardy had a developed a connection to the College, which had invited him to become an honorary fellow in 1922 (he received an honorary doctorate from the University in 1920). The idea perhaps emerged from Hardy’s friendship with the energetic director of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, Sydney Cockerell, who had written to the famous novelist in 1911 in an attempt to persuade him to donate a manuscript to Cambridge. On the subsequent visit to Hardy at Max Gate in Dorset, a plan was hatched to divide the manuscripts of Hardy’s works among universities and public institutions, with Cockerell writing to various librarians and museum directors proposing the donations; as a result Jude the Obscure headed to the Fitzwilliam. Cockerell was well aware of the collectability of Hardy’s manuscripts, as well as their importance to Hardy’s future reputation.

Hardy’s last long journey was to the College in June 1922, stopping at Salisbury Cathedral along the way, as well as the village of Fawley, whose churchyard contained the graves of some of his ancestors and whose name provided the surname for Jude of Jude the Obscure (the village is rendered as Marygreen in that novel). At Queen’s he was met by Godfrey Elton (then dean) and F. D. Chattaway (the chemistry fellow). As Elton noted, ‘Neither Chattaway nor I had met Hardy before, but I felt confident that we should recognise the now legendary figure from his portraits. It was almost like awaiting a visit from Thackeray or Dickens.’ He took tea with the provost, and the next day had lunch in the Common Room, accompanied by fellows and their wives, followed by a photograph in the Fellows’ Garden, with Hardy ‘in his Doctor’s gown with his new colleagues.’ Elton had some reservations about the tour of the College, which was taken a ‘trifle too fast’, and ‘wished that it had been term-time and that [Hardy] could have seen some of the younger life of the place, which one felt in some ways he would have preferred to Tutors and Professors’. Hardy did had time to ‘pause reflectively before Garrick’s copy of the First Folio’. Hardy then took in the sweep of the High Street, and ‘unwearied, he asked for the Shelley Memorial.’ A visit to John Masefield at Boar’s Hill and evensong at New College followed.[1]

Although Hardy had made his name as a novelist, he had not published one for thirty years, and instead had focussed on poetry. A recent collection (edited with Cockerell’s help) Human Shows, Fair Phantasies, Songs and Trifles had been published in 1925, and sold 5,000 copies almost immediately. Two further editions were printed before the end of the year, along with an American edition. As his biographer Claire Tomalin notes, ‘Hardy had become a popular poet.’[2] Hardy aimed for Winter Words to be published on his eighty-eighth birthday in June 1928, although the ellipses from the manuscript that remain in the published forward suggest that he considered a publication on his eighty-ninth or even ninetieth a hopeful possibility. However, he feel ill in December 1927, although he continued working on the collection, completing ‘Christmas in the Elgin Room’ for publication on Christmas Eve in The Times and adding a final work, ‘He Resolves to Say No More’ (‘I’ll let all be./And show to no man what I see.’) Taken ill with a failing heart, he died on 11 January 1928.

Other interested parties (including Cockerell) quickly moved into gear, and a high-profile funeral at Westminster Abbey was swiftly arranged – although on the understanding that Hardy’s body would have to be cremated in the interests of space in Poets’ Corner. Hardy had expressed a wish to be buried in the churchyard in Stinsford, so Cockerell arranged for a local surgeon to removed Hardy’s heart. Attended by his brother, Henry, it was buried in Dorset at the same time as the ceremony at the Abbey. Here, the urn containing the ashes of the rest of his body (and Cambridge gown) had been placed inside a coffin-shaped case, whose pallbearers included the Prime Minister, the leader of the opposition, Rudyard Kipling, Edmund Gosse, George Bernard Shaw, JM Barrie, John Galsworthy, Allen Beville Ramsay (Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge) – and E. M. Walker, pro-provost of The Queen’s College, Oxford.

True to Cockerell’s intention, manuscripts were sent to various institutions. Winter Words duly arrived at Queen’s. A stray, ‘He resolves to say no more’, arrived via donation in the 1950s, and the College arranged for the collection then to be bound at the Bodleian in black leather, with gold tooling and green marbling. The collection of ‘quirky, vivid poems’ (Tomalin) is notable for its metrical invention, and as one biographer, Robert Gittings, notes ‘though not his finest volume, represents almost every manner of Hardy’s verse, lyric, narrative, reflective, humorous, love-poems, nature-poems, epigrams, dialogue, and philosophical pieces. Nothing like it had been produced by a man of his age since Goethe.’[3]

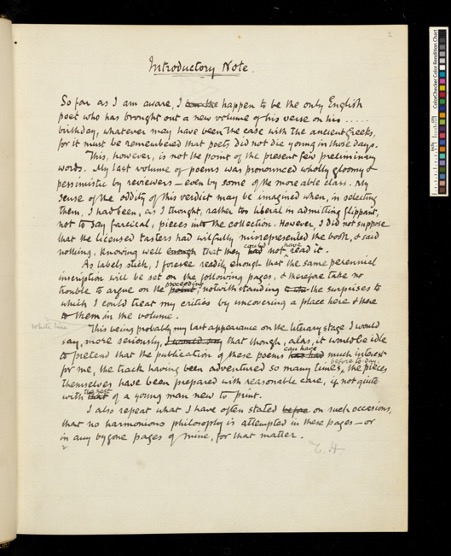

Introductory Note, Thomas Hardy

Hardy faced the charge of pessimism head-on in the collection’s forward: ‘My last volume of poems was pronounced wholly gloomy and pessimistic by reviewers – even by some of the more able class… As labels stick, I foresee readily enough that the same perennial inscription will be set on the following pages’. Despite this, reading the poems, even the arrival of spring itself might not bring great comfort. As his wife Florence noted during Hardy’s final days working on the collection: ‘when he came down to tea he brought one to show me, about a desolate spring morning, and a shepherd counting his sheep and not noticing the weather.’[4]

Winter Words has now been digitised and can be read online via Digital Bodleian.

[1] Florence Emily Hardy, The Later Years of Thomas Hardy (1930), p. 232.

[2] Claire Tomalin, Thomas Hardy (2007), p. 358.

[3] Robert Gittings, The Older Hardy (2001), p. 207.

[4] Florence Hardy, Thomas Hardy: the later years

Header image: Queen’s Lane in the snow, ©OUImages /John Cairns