Dr Matthew Shaw, Librarian

Among the treasures of the College Library is a book closely related to an invention that transformed human history. Acquired in the 1840s, the Catholicon is the only book held by an Oxford college attributed to Johannes Gutenberg (d. 1468), the former goldsmith famed for the invention of the moveable-type printing press at Mainz. This large printed book of nearly 400 folios is also at the heart of a lively academic debate about the origins of printing.

The genius of Gutenberg’s process was in part its coordination of several technologies and systems. He drew on goldsmithing techniques to create moulds for the casting of reusable type and devised a recipe for printing ink created from lamp soot, varnish, urine, and egg whites. Benefiting from pre-existing markets for manuscript books, an understanding of papermaking derived from the Arab world, and an appetite for religious, legal, and mercantile texts, his press helped to usher in a world increasingly shaped by the written word. By 1500, print historians estimate that at least nine million books had been printed.

Gutenberg’s best-known product was the 42-line Bible, also known as the ‘Gutenberg Bible’, designed in almost every detail to resemble a manuscript, including some that were printed on vellum. Just under 50 copies are known to survive; only 25 are complete. The Bodleian acquired its ‘Gutenberg’ (shelfmark Arch B b.10,11) in 1793 for £100 after it was auctioned by the cash-strapped Cardinal Loménie de Brienne (who owned two copies).

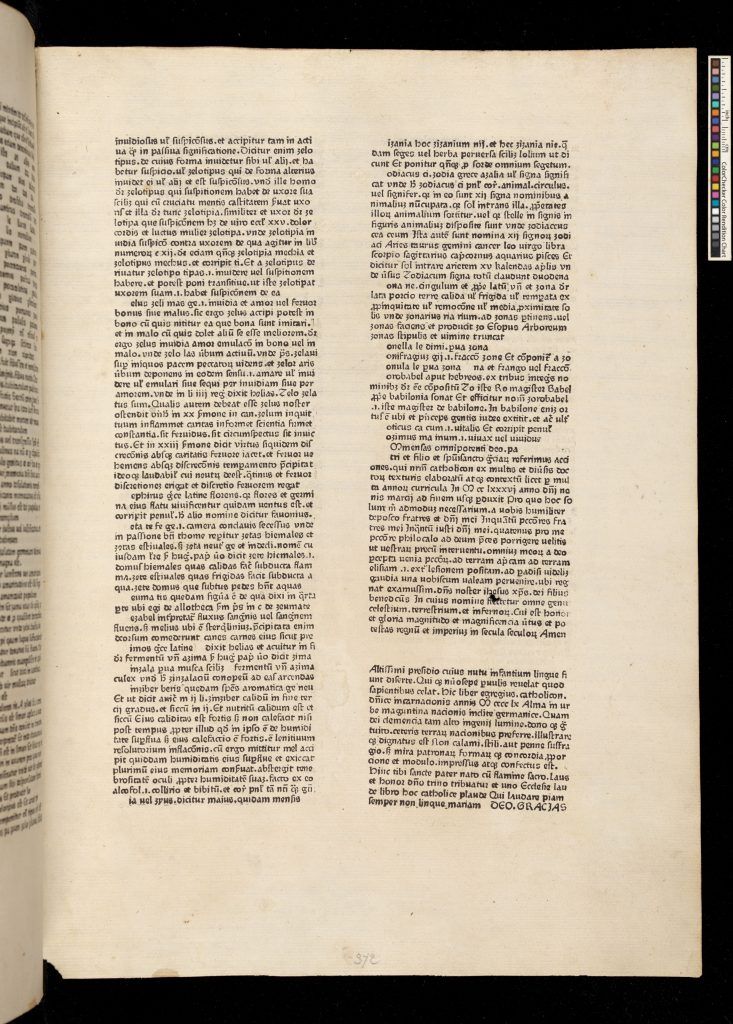

The College does not yet possess a Gutenberg Bible, but since the 1840s, it has held a copy of the Mainz Catholicon: the first printed version of a dictionary of medieval Latin, originally composed by the Dominican friar Giovanni Balbi (d. 1298). It contains four treatises on grammar and an alphabetical vocabulary of some 15,000 Latin words and their definitions. Always in demand by scholars, Balbi’s text was a good bet for the new technologies of print. While the Latin-verse colophon (the statement about its production at the end of the text, from the Greek for ‘finishing touch’), notes the ingenuity and skill of the printer who fashioned the book ‘without the use of a reed, stylus, or pen’ and includes for the first time in a printed text the place of publication (Mainz), it does not name him. But since at least 1471, when Guillaume Fichet, a Sorbonne professor, wrote about the spread of printing, the anonymous work has been identified as a Gutenberg. Certainly, when the College acquired it in the 1840s, it was sold as ‘Gutenberg’s Catholicon’, and was recorded in the catalogue as such.

…this noble book, the Catholicon, has been printed and completed as the years of the Lord’s incarnation number MCCLX [1460], in the city of Mainz within the great German nation… without the use of a reed, a stylus, or a pen, but rather by the wonderful concord, proportion and measure of punches and forms.

[Catholicon, colophon]

Closer examination of the surviving copies of the book raises a host of questions that have been exercising scholars. The colophon records 1460 as its year of completion, but it was issued in four variants: three on paper and one on vellum. The date of the paper used in the various issues is puzzling. Watermarks and comparisons with other texts date the papers to after 1460, 1469, and 1473, with the latter two dating from after Gutenberg’s death. Most curiously, the setting of the type in the various editions is identical, meaning that the ‘moveable type’ must have remained in place for several years; a puzzle for a time of tumult in the new print shops when type was limited and expensive.

Various ingenious explanations have been put forward, based on observations such as the apparent pairing of lines of type, the use of nail heads on the paper, and the hint of wires wrapped around slugs of text. Perhaps, Paul Needham has suggested, the type was tied together and placed into clay, allowing metal casts of two-line slugs to be made for future impressions. In contrast, Lotte Hellinga argues that the mix of editions and papers suggest a collaborative project between the various printers in Mainz, who each used their own presses and stock of papers to make up the books. The debate continues today, both in scholarly publications and in lively online discussion.

Even in this digital age, physical copies, such as the one held by the College, preserve evidence that may one day resolve this conundrum from the birth of print, or at least give us a richer understanding of what was involved in the making of a book. Mindful of this, the Library has recently digitised the College’s copy, making it available online for future study, continuing the expansion of knowledge begun by Gutenberg, and underscoring the College’s ongoing support for global scholarship.

The Catholicon is available to view on Digital Bodleian: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/partners/queens/.

![A book page from 1613 with the title 'Double books to be exchanged according to [the] pleasure of...'](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Double-Books-cropped.png)