Dr Matthew Shaw, Librarian

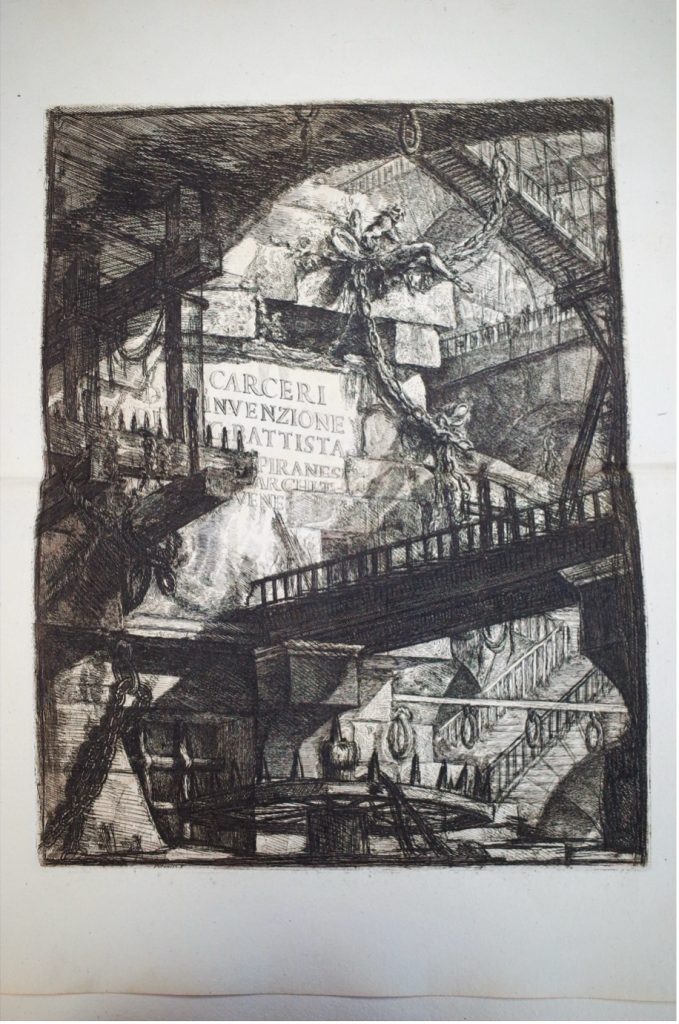

Among the many treasures held by the College Library, the 16 large volumes of prints made by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778) must rank as one the most compelling. Much sought after by collectors in the eighteenth century keen to acquire his etchings of classical Roman antiquities, Piranesi’s fame also rests on 16 etched and engraved plates known as the Carceri d’invenzione, which dramatically depict a series of giant imagined prisons, complete with tortured prisoners, haunting staircases, and inky shadows.

These scenes, which Piranesi began in his youth and then reworked over time, have inspired generations of writers, artists, and musicians, providing materials for the gothic and romantic artistic movements, giving visual form to a series of psychological nightmares or dreams.

Piranesi, who came from a family of Venetian stonemasons, had broad ambitions. He aspired to be an architect, and his works are a testament to this desire, along with his antiquarian obsessions and fantastical visions of ancient restorations. As a pamphleteer, he weighed heavily into the heated debate on the supremacy or origins of Roman architecture, arguing for its native, Etruscan origins, rather than Greek antecedents.

Complete sets of his works are relatively rare, especially ones in as good condition as the College’s, which are also finely bound by Jean-Claude Bozérian, the noted French neo-classical bookbinder (who bound books for Napoleon). The College acquired it the 1840s, thanks to the bequest by Old Member Revd Robert Mason, and the set is augmented by a particularly rare pamphlet, Piranesi’s Lettere di giustificazione scrittea milord Charlemont e à di LVI. agenti di Roma (1757). This attacked Piranesi’s former artistic patron, James Caulfield, 1st Earl of Charlemont, a noted Irish patron of the arts, who spent eight years on his Grand Tour, and who failed to finance the publication of Piranesi’s Le Antichità romane (1756) despite a promise of a subvention after the work had begun. The etchings in the Lettere demonstrate the initial patronage of Charlemont, and how his lack of support caused his name to be removed from the dedication page. As well as a bibliographic treasure, suppressed soon after publication, it is a powerful record of the changing relationship between artist and patron in the eighteenth century. For Piranesi, the nobility of creation is what stands the test of time, not the largesse of the patron.

As well as a bibliographic treasure, suppressed soon after publication, it is a powerful record of the changing relationship between artist and patron in the eighteenth century.

Piranesi presented copies of his polemic to his supporters. As such, the College’s copy originally belonged to Thomas Hollis (1720–1774), an English political philosopher and republican, who donated a vast number of books to English and American libraries (notably Harvard) and nominated Piranesi to be a Fellow of the London Society of Antiquaries. This book is not bound by Bozérian, but by one of the London binders who worked for Hollis and attempted to keep up with his bookbinding – most likely Richard Montagu, who used similar tools for his commissions for David Garrick. Soon after this volume was bound, Hollis commissioned a range of bespoke bookbinder’s tools using classical Roman symbols. While the College’s copy of the Lettre lacks these decorations, it does contain an illustrated inscription by Piranesi to Hollis, depicting the burin he used for his enduring creations, and the exceptionally rare four-page letter of retraction by Piranesi to Charlemont, dated Rome, 15 March 1758.

![A book page from 1613 with the title 'Double books to be exchanged according to [the] pleasure of...'](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Double-Books-cropped.png)