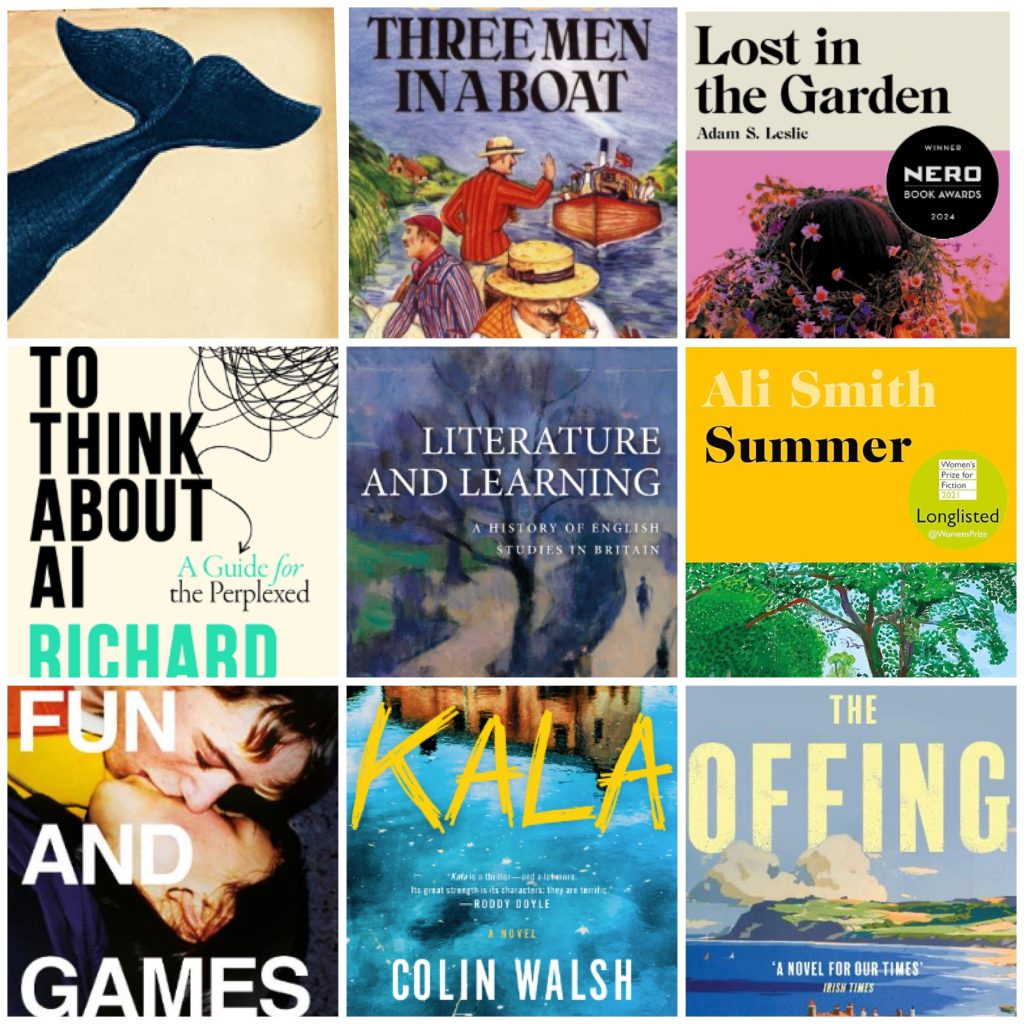

It’s that time again! Our brilliant Library team have shared their top picks for summer reading. It’s a mix of the unexpected, the thought-provoking, and the utterly absorbing. Whether you’re chasing sun or shade, get ready to discover something you didn’t know you needed to read.

Sarah Arkle, Deputy Librarian

Very late to the party, I have recently got into Ali Smith; she has a very playful way with language that I really enjoy. This academic year, I’ve been working my way through her Seasonal Quartet, beginning last October with the first of the set Autumn, followed by Winter, then Spring. My first recommendation for summer reading therefore is the final instalment (unless you count the additional Companion Piece) Summer, which I am yet to read, but will be moved to the top of my TBR now we’ve reached the summer solstice. I don’t believe it is necessary to read them in any particular order as each book is quite distinct, but I chose to read them in line with each season, which has been a pleasant reading experience that I would recommend. The novels were written shortly after, and partly in response to, the political landscape we found ourselves in post-Brexit referendum in 2016, so they feel as fresh and relevant as they did almost ten (!) years ago. Don’t let that put you off, Smith’s writing is fun and hopeful, I think we can all benefit from a bit of that these days.

Smith’s writing is fun and hopeful, I think we can all benefit from a bit of that these days.

My second recommendation is a book I read a few years ago now, but remember enjoying and feels seasonally appropriate – The Offing by Benjamin Myers. I’m a big fan of Myers’ work as he sets his novels in the north of England, and The Offing is no different. It tells the story of a young man named Robert, who leaves his village in County Durham on foot and walks to Robin Hood’s Bay where he strikes up an unlikely friendship with an older woman named Dulcie who introduces him to poetry and wild swimming. It isn’t without its darker parts but it is on the whole a book filled with warmth which I read in less than a day during the 2020 lockdown, according to the little app I use to track what I’ve been reading – I suppose there wasn’t much else to do back then.

Lastly, I really loved Ann Patchett’s novel Tom Lake which I read late last summer. It’s about a woman named Lara, whose three grown up daughters are home – I think for lockdown, if I remember correctly (sorry to mention it again, though from what I recall I don’t think Covid looms large over the novel as a whole). Whilst picking cherries in their orchard, she tells them the story of a romance she shared in her younger years with a man who went on to be a famous film star. It is a bit of a departure from my usual book-based diet of horrible weird fiction and I was surprised by how much I enjoyed it. Although the book itself is technically based in spring, I think it could definitely be enjoyed on a sun lounger somewhere warm.

Matt Shaw, Librarian

You probably don’t need a College Librarian to recommend a selection of thrillers, spy novels, or other page-turners suitable for the Eurostar platform. So, instead, some possibilities from the non-fiction shelves.

The first is the wry and lively Literature and Learning: A History of English Studies in Britain by Stefan Collini. Finally, someone has come to the rescue of Q (no, not that one) and Walter Raleigh (no, not that one either). There’s also a lot on what a university is about, or has been in the past. You can also read the book online, if your Bod Card is in good order and your suitcase too stuffed for 400pp hardbacks.

On the digital front, it’s probably worth the quick run through Richard Susskind’s How to Think About AI, which provides a good framework for thinking about how to respond to inevitable questions in the hotel bar from a new acquaintance about whether your job is doomed to AI-extinction. With Susskind’s legal and academic background, it’s particularly on the money for lawyers or former philosophers; you can also take succour that no AI agent will ever enjoy the taste of the negroni you are drinking in the same way.

‘How to Think About AI’ provides a good framework for thinking about how to respond to inevitable questions about whether your job is doomed to AI-extinction.

Speaking of barstools and books, if your holiday is especially long, and you’re feeling lucky, you may be able to snag the American edition of Rumors of my Demise: A Memoir by Evan Dando before Michaelmas Term and possibly enjoy a trip back to an alt-millennium. Should this publication schedule prove over-optimistic, you’ll certainly be able to grab Catherine Clarke’s A History of England in 25 Poems before term starts, and perhaps see if Collini’s fretfulness about Eng. Lit.’s possible retreat to a shrinking enclave of a ‘smaller number of enthusiastic students and specialist teachers’ might be assuaged.

As for me, I’m looking forward to reading Emily Gee, Hostel, House and Chambers: accommodating the Edwardian working woman in book – rather than proof – format.

Felix Taylor, Library Assistant

Now that I’ve begun cycling to work and back again, audiobooks have become a new source of time-passing entertainment. As long sections of the commute pass along the riverbank, it is appropriate that my two summer recommendations are set on, or deep within, the water. Philip Hoare’s Leviathan: or the Whale, narrated by Philip Pope, is a book mostly about Herman Melville and the writing of Moby Dick, so prepare for panoramic scenes of the New Bedford whaling industry in the early nineteenth-century and the history of spermaceti oil in candles and streetlamps and even (much later) in space, due to its very low freezing point. Whaling was a dangerous but economically enriching pursuit, and Melville’s novel universalises it as man’s Shakespearean search for meaning (or revenge, or death, or anything you like). Hoare’s book is less a natural cetacean history and more of an account of a personal obsession, a love letter to Moby Dick. The autobiographical asides can seem weak at times, but it’s an engaging and well-narrated dive into the cultural impact of the whale over the last two centuries.

The other audiobook I can suggest is Jerome K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat – another watery-themed story, but one of travel, wit, slapstick, and a smattering of local history. Read by the veteran British actor Ian Carmichael, the short book follows three hypochondriacs and a dog who decide that a week on the Thames will heal their fragile constitutions. From Kingston to Oxford, they row leisurely (and incompetently and haltingly) downstream, stopping when they feel the urge to sample the inns and to refill their hamper. The original intention of J, the narrator, was to write up the trip into a guidebook for that stretch of the river, although this ends up being shoved to the side in favour of more exciting exploits. It’s funny, and was clearly very funny when it was published in 1889 because it made Jerome’s name and has led to sequels, adaptations and parodies.

Read by the veteran British actor Ian Carmichael, the short book follows three hypochondriacs and a dog who decide that a week on the Thames will heal their fragile constitutions. It’s funny, and was clearly very funny when it was published in 1889 because it made Jermone’s name.

Lauren Ward, Assistant Librarian

As I write this at the start of the long vac, it happens to be swelteringly hot in Oxford. In that vein, the books I’ve chosen to put forward are ones set in and about summer, though their takes on the season vary quite wildly.

I’ll start with the strangest of the three. Adam S. Leslie’s Lost in the Garden is set in an and England experiencing perpetual summer, and one that also happens to be plagued by solid, violently-inclined ghosts. In this alternate England everyone is raised with ‘don’t go to Almanby’ being an accepted piece of folk wisdom – so, of course, that’s exactly where Rachel, Heather, and Antonia decide to go. What follows is an increasingly psychedelic road-trip haunted by eerie voices crackling over shortwave radio, the jingling of ice cream vans which never appear, and, of course, the ghosts roaming the countryside. Don’t let the relatively chunky size (450 pages) of this put you off – it’s a genuine page-turner full of snappy dialogue, plenty of humour, and nostalgia for childhood summers and the unique weirdness of English village life. Read with an ice cream close at hand (trust me).

What follows is an increasingly psychedelic road-trip haunted by eerie voices crackling over shortwave radio, the jingling of ice cream vans which never appear, and, of course, the ghosts roaming the countryside.

Also nostalgic, but featuring zero ghosts, is Fun and Games, John Patrick McHugh’s debut released this year. In it, 17-year-old John Masterson spends his final summer before going away to college in Galway working mind-numbing shifts at his hotel job, going to parties, and worrying about his relationship with his coworker Amber. McHugh really captures how constantly tragic and hilarious being a teenager is, managing not to let humour get in the way of more poignant moments. You’ll laugh, you’ll definitely cringe, and you’ll most likely be glad you never have to be a teenager again. This one can be found in the General Collection at Gen McH and if you don’t trust my recommendation, it’s also been blurbed by Sally Rooney.

Finally, Kala by Colin Walsh is another piece of recent Irish fiction I’ve enjoyed immensely. It follows Helen, Joe, and Mush, who are thrown together in their hometown of Kinlough as adults after years apart. As teenagers they spent the summer of 2003 in an inseparable group of six friends, the centre of which was Kala Lannan. When Kala disappeared later that summer the group fractured and 15 years later unanswered questions remain. This is an excellent slow-burn mystery about the secrets simmering under the surface of a small, ostensibly respectable, town. More importantly though, Walsh’s characterisation of the three friends both in their youth and as adults is second to none – he has such a keen eye for the feverish nature of teenage friendships and rebellion, and captures perfectly why Kala was so important to the group. If you’re in the mood for a gripping vac read, you can find this in the General Collection at Gen Wal.

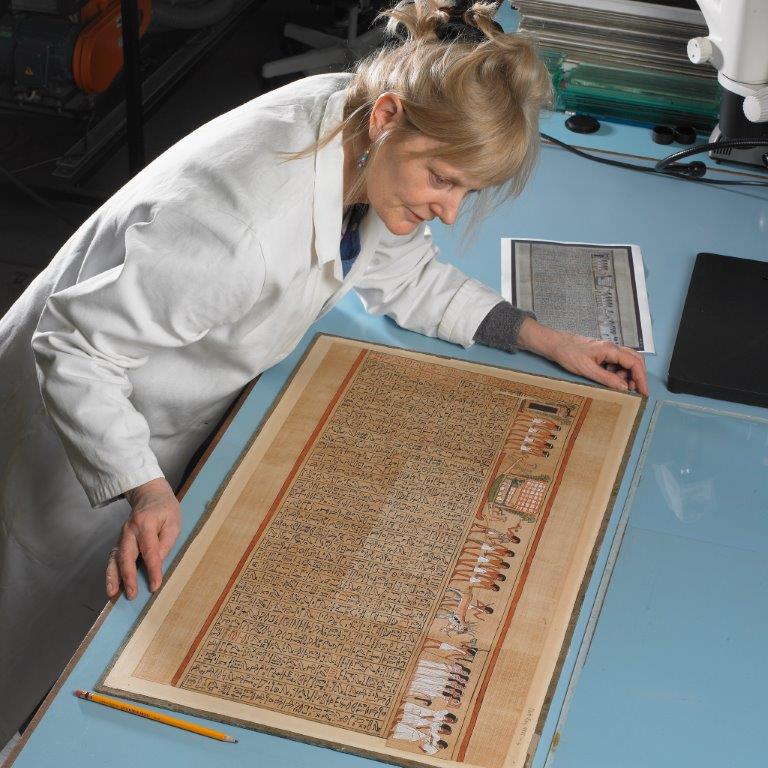

Header image: John Cairns

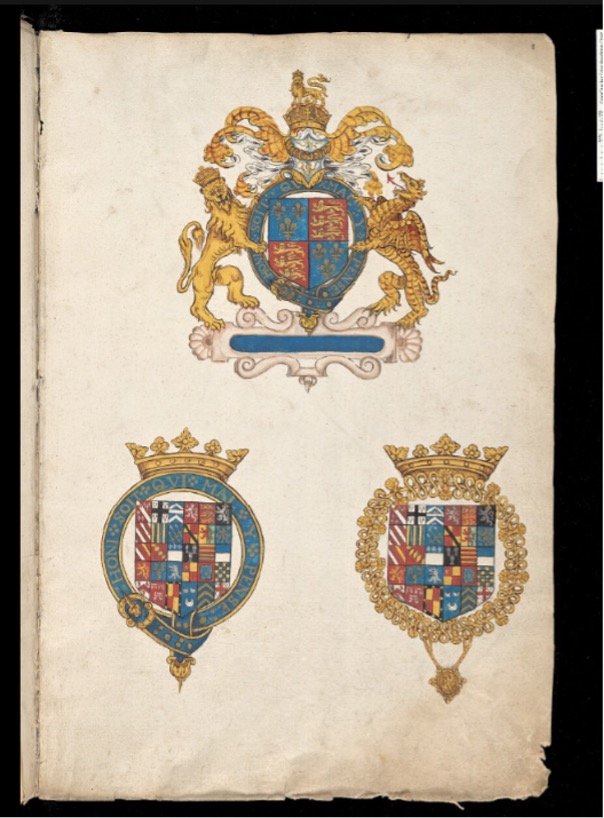

![The arms of [the] Citie of London, Queen's MS 72. Image: The Provost and Fellows of The Queen’s College, Oxford. CC-BY.](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/citie-of-London-arms.jpg)