From liver disease to the archaeology of trees, What’s Brewing at Queen’s? brings graduate research out of the seminar room and into a relaxed, sociable setting. We spoke to the series’ organiser, Sanjna, about how this informal lecture series is creating space for curiosity, conversation, and cross-disciplinary exchange.

Sanjna

“What’s Brewing at Queen’s is an informal lecture series, designed to give current MCR (graduate) students the chance to talk about their research in a relaxed setting. The lectures are short and aimed at a non-specialist audience, with the goal of sparking conversations between members of the College across different disciplines. Queen’s students do a lot of very interesting research, and the goal is to create a space where students can learn from each other, without the pressure of a more formal academic environment.”

Where did the idea come from?

The lecture series itself was inspired by an event called “Lectures on Tap”, run in New York and other cities around the world, where academics give light-hearted lectures for a lay audience in a bar or brewery, resulting in an entertaining event which also contributes to public engagement with research. One of the highlights of Oxford’s collegiate system is access to an incredibly diverse academic community outside your own discipline, and we wanted to draw on that community in a more fun, light-hearted way.

One of the highlights of Oxford’s collegiate system is access to an incredibly diverse academic community outside your own discipline.

What does a typical evening look like and how is it different from a more traditional academic talk?

A typical evening involves a small group of College members gathering in a cosy venue – most recently the Provost’s Lodgings – to listen to short lectures by two MCR members. The lectures are always delivered over drinks and snacks, resulting in a very relaxed, fun environment, and they are usually interactive. Unlike more traditional academic talks, our lectures are aimed at a non-specialist audience, and are intended to spark discussion. The goal is to make learning accessible and fun, and some speakers have even taken a more comedic/entertaining approach to explaining their research. Since the audience is small and also made up entirely of fellow College members, the environment is more low-stakes, and we hope that this removes any pressure speakers may otherwise face while presenting in a more formal academic setting.

Why was it important to create a space where graduate students could talk about their research informally, and to a mixed audience?

Interdisciplinary conversations can have immense value: they allow one to view their research questions with a new, more diverse lens, and can be a springboard for new ideas and collaborations. Especially as students specialise in their training with higher postgraduate degrees, having access to interdisciplinary spaces becomes even more crucial. However, graduate students typically have a busy schedule with several formal academic commitments, so we felt that adding another would create more barriers to participating in these conversations. Therefore, it was important that we made the environment as relaxed as possible to encourage participation. We want this series to spark more organic conversations that continue even outside the lecture – in the MCR, Hall or Beer Cellar as well. From an audience perspective, the informal setting is also important because it creates a space where there is less hesitation to ask questions. Since the audience is assumed to be non-specialist, there are no “stupid questions” – everyone is here to learn, and all questions are welcome, which makes it easier to engage with the speaker during the Q&A.

Interdisciplinary conversations can have immense value: they allow one to view their research questions with a new, more diverse lens, and can be a springboard for new ideas and collaborations.

What kind of research topics have featured so far, and have any conversations or moments really stayed with you?

The lectures so far have spanned a breadth of topics, ranging from improving diagnostics of liver disease to alternative paradigms for understanding reparations for human rights violations. Upcoming lectures include topics such as the archaeology of trees and the mechanisms underlying inflammation. One thing that’s stood out to me has been that while disciplines vary in the questions they seek to answer, the approaches and tools they employ can be useful even beyond that discipline. For example, a speaker who was researching tree-killing in Canada was using tools and tests usually used by chemists, while another speaker studying music and the cultural experience of listening was combining approaches from musicology, the processing of sound, and audiology in her research, proving that modern-day research is a lot more fluid and interdisciplinary than one might think.

How do speakers approach explaining their research to a non-specialist audience?

We’ve had very engaging speakers so far that have done a wonderful job making their lectures accessible to non-specialists. Speakers vary in their approach to meeting this goal, but typically, lectures are devoid of jargon and technical terms and focus on the bigger picture rather than minute methodological details. There is an emphasis on providing enough context, so the audience understands the story, without getting overwhelmed by details. We’ve also had some very interesting analogies used to explain concepts, and some fantastic visual representations as well. Not all research stories are complete, and those often make for very interesting lectures, since they invite further thought and discussion, and it is fascinating to see how differently trained academics approach the same questions.

What do you think graduate students gain from organising and speaking at events like this, beyond sharing their research?

There is immense value in making your research accessible to a non-specialist audience. Doing so demands that you have a clear and focussed understanding of the problem or question your research seeks to answer, and preparing a lecture helps one narrativise one’s research into a story, which is an important skill for students to develop. Additionally, talking to students outside of your field can help you view your questions with fresh eyes, or bring to light new tools and approaches one could try as well.

If you were trying to convince someone to come along for the first time, what would you say to them?

Studying at Oxford gives you the unique opportunity to interact with brilliant people in all disciplines, who do cutting-edge research. Learning about all the latest research can be incredibly fun, and who better to learn from than the students at the very frontline of it! I’d encourage anyone who wants to learn something new, in a relaxed setting with no pressure, to come along to a lecture with an open mind.

Learning about all the latest research can be incredibly fun, and who better to learn from than the students at the very frontline of it!

What’s surprised you most about how people engage with research in this kind of relaxed setting?

I’ve been pleasantly surprised by the nuanced, and often quite detailed level of engagement speakers get during the Q and A. Even in this relaxed setting, the audience is very perceptive and plays close attention. We’ve had some very interesting questions come up, not only direct questions about lecture content, but also questions that have invited further discussion beyond the scope of the short lecture and made for very interesting conversation at the drinks reception afterwards.

In this interview, first-year PPE student Tresor shares his honest take on choosing his degree, finding confidence through tutorials, and making the most of opportunities at Oxford — alongside a clear-eyed approach to work, rest, and ambition.

What drew you to your subject at Oxford, and what’s been the most surprising or enjoyable part of studying it so far?

I am tempted to give my robotic interview ready answer, but I will be honest. I knew I wanted to do economics because I enjoyed it A-level and I knew I wanted to be a banker so I thought economics would help. But I also wanted to be like those Greek statues who are in a thinking pose so I applied for PPE.

How have tutorials, lectures, or informal discussions at Queen’s shaped the way you think or approach problems?

In terms of how I think, it’s highlighted my processing speed is relatively slow, but the information sticks hard.

Can you tell us about a moment at Queen’s when you felt particularly supported or encouraged?

Jem Page tutorials. Couldn’t find my footing in logic but he gave me props when he saw improvement.

You’ve recently secured places on spring insight weeks. What sparked your interest in exploring this area, and how did you go about applying?

In all honesty, I want to be stupidly rich so I can give back to my community – so settled on banking. I tried to apply the day it came out, with a large amount of information at the firm and potentially having spoken to someone at the firm already – just to get my foot in the door.

Do you feel your time at Queen’s has helped you feel more confident exploring opportunities you might not have considered before coming to Oxford?

Yes, my time at Queen’s has helped me feel more confident in exploring opportunities. I just try applying for anything and everything now because it seems everyone here is doing that.

How do you balance academic work with extracurriculars or downtime?

I have a 100/100 work life balance. Go all in on the work so I can go all in when I relax or go out. It can somewhat clash but it seems to be working well.

What would you say to a prospective student who’s interested in your subject but unsure whether they’d fit in at Oxford or at Queen’s?

Queen’s is the best college in Oxford see: end of term event. There shouldn’t be a worry about ‘fitting in’ to Oxford. You’ll be completely fine because the way the colleges are structured makes friend-making extremely easy. When this is combined with extracurriculars, hobbies, and going out, you will fit in.

What’s your favourite study space?

Either my room or the New Library.

Can you recommend a book?

The Valuation Book by by Kenneth Lee, Mark Aleksanyan, Matthias Meitner, Neil Pande.

When a former head of government is sentenced to death in absentia, the world tends to fix its gaze on the headline. But behind the spectacle of former Prime Minister of Bangladesh Sheikh Hasina’s conviction lies a far more complex set of questions about what justice really means in moments of national reckoning. In this conversation, a Queen’s DPhil student and human rights practitioner Taqbir Huda reflects on Bangladesh’s July revolution, the moral authority and fragility of international human rights law and criminal law, and the uneasy role that social media, digital evidence, and politicised courts now play in shaping public understanding of atrocity.

Drawing on years of documenting state violence and thinking critically about reparations, punishment, and due process, he offers a frank account of why justice must be more than symbolic – why it must be fair, durable, and capable of withstanding the pressure of both popular outrage and political revenge. Fresh from appearances on Al Jazeera and DW, Clarendon Scholar Taqbir Huda tells us more.

Do you think justice has been served in the sentencing of Sheikh Hasina or is the ruling purely symbolic? How do you define justice and what makes justice meaningful in practice rather than just in appearance?

For many Bangladeshis, there is a real sense of moral vindication in seeing a brutal dictator held legally responsible for the mass killings that occurred during a popular uprising. In that sense the judgment is perhaps not purely symbolic: it also has a communicative dimension of the kind Antony Duff writes about, in that it publicly condemns the shootings of students and civilians in the July revolution as state sponsored crimes against humanity under international law, rather than unfortunate excesses. An official condemnation from the state which acknowledges this difference matters greatly for realising justice.

At the same time, justice is not only about obtaining a conviction, but also about how likely that conviction will translate into actual accountability. A death sentence delivered in absentia, after a hasty trial that did not meet fair trial standards, risks looking more like victor’s justice than the kind of impartial accountability we owe to the victims. To me and most other human rights practitioners, justice for mass atrocities becomes meaningful when at least four elements come together: truth about what happened, accountability that is based on credible evidence and fair process (so no one can raise doubts about the legitimacy of the conviction), some form of reparation for victims and genuine institutional reform designed to prevent recurrence of past abuses. If any or all of these elements is missing, then justice becomes less meaningful.

To me and most other human rights practitioners, justice for mass atrocities becomes meaningful when at least four elements come together: truth about what happened, accountability that is based on credible evidence and fair process (so no one can raise doubts about the legitimacy of the conviction), some form of reparation for victims and genuine institutional reform designed to prevent recurrence of past abuses. If any or all of these elements is missing, then justice becomes less meaningful.

When you look at high profile trials like this one, what are the essential legal principles that must be protected if we want a fair process?

The basic principles under international criminal law are quite simple: the accused must be presumed innocent, have the right to be present at their trial, and be represented by independent defence counsel who act on their instructions rather than on the government’s and the ability to call and cross examine witnesses on equal footing with the prosecution, and the defendant must have a real right of appeal.

A novel challenge in cases like this is the emergence of evidence on social media. In Bangladesh, the July uprising generated an enormous amount of digital evidence: photos and videos of protesters being shot, run over by vans, thrown off the back of trucks, or beaten to a pulp by security forces and party cadres. That material has been vital for documenting what happened, but it also creates a risk that public opinion hardens around clips seen on social media long before any court evaluates them.

Verifying authenticity in a criminal trial involves much more than watching a clip on a phone. You need to establish where the file came from, how it was stored, and whether it was altered. During the revolution, I was working day and night with the Evidence Lab at Amnesty International to verify the hundreds of photos and videos that we received from partners and witnesses on the ground as well as open sources. This included checking metadata, time stamps and geolocation, matching buildings and landscapes on screen to real locations, comparing shadows and lighting, and asking forensic experts to analyse the audio and video for signs of editing or artificial generation. Later, working with colleagues at Tech Global Institute, which holds one of the largest archives of digital evidence of the July atrocities, has really brought home to me how the rise of artificial intelligence makes this even more complex. AI generated or altered content can look and sound convincing, which means courts have to be especially careful not to treat viral clips as proof beyond reasonable doubt without proper forensic testing and adversarial challenge in court.

AI generated or altered content can look and sound convincing, which means courts have to be especially careful not to treat viral clips as proof beyond reasonable doubt without proper forensic testing and adversarial challenge in court.

In that sense, the digital turn can put real pressure on the presumption of innocence in high profile cases: by the time a trial starts, many people already feel they “know” what happened from what they have seen online. A court that truly upholds the right to a fair trial has to be seen to push back against that pressure, not simply cave into it. In a case of this magnitude, the integrity of the process is just as important as the moral culpability of those who end up being punished.

Many people have noted that the tribunal used in this case was originally set up under the same leader it has now convicted. What does that tell us about the importance of judicial independence?

There is a striking irony in seeing Sheikh Hasina convicted by a tribunal that her own government created and used extensively against its political opponents, which led to many being able to seek asylum here in the UK under the Human Rights Act, but also led to the execution of high-profile opposition leaders who were not able to escape. Sheikh Hasina being awarded the death sentence by the very tribunal which she set up to execute her foes should serve as a sobering reminder to autocrats around the world: once you cull judicial independence and embed authoritarianism into a legal system, you may one day be subject to the same system you built. So you should not do unto others, what you do not want others to do unto you.

Judicial independence is not only about having in place formal guarantees in the text of the law, but about building a culture of adjudication that can resist pressure from whichever government happens to be in power.

Judicial independence is not only about having in place formal guarantees in the text of the law, but about building a culture of adjudication that can resist pressure from whichever government happens to be in power. Even a tribunal born in a deeply politicised context can, under a different constellation of social movements, professional ethics and international support and scrutiny, start to move in a more principled direction.

You have drawn on the phrase “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” In legal terms, what does that mean and can systems built under authoritarian rule ever fully reform themselves from within?

In this context, “the master’s tools” are the very set of laws and institutions an authoritarian regime relies on to consolidate power: special tribunals with special emergency powers, vaguely defined offences such as “tarnishing the image of the state” and normalising exceptional derogations from human rights in the name of national security. These tools are designed to make the exercise of arbitrary powers look like lawful governance. As a human rights defender, I have spent the past decade censoring myself to escape the tools Sheikh Hasina’s authoritarian regime used to criminalise dissent. In 2022, I took the risky decision to join Amnesty International, an organisation blacklisted by the Hasina government at the time, to expose the human rights abuses it was committing in Bangladesh. I investigated and documented over 50 such cases: from enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings to arbitrary detention etc.. I had to keep my affiliation a well-guarded secret. The last thing I wanted was as to face a criminal case for ‘spreading propaganda’ against the state – which had become the default response to any dissent. To avoid this risk, I used a pseudonym, burner phones/ email IDs; requested my colleagues to front our publications on Bangladesh; and avoided any public engagements, all to escape the state’s ever broadening radar of surveillance. I even added and then removed Amnesty from my LinkedIn. That’s how successful the state was in catalysing a culture of fear.

All this changed during the July 2024 revolution, when I decided I could no longer hide. I accepted an interview with DW News, the first international media outlet to report what was happening. That interview reached a million views in 24 hours and soon enough I found myself speaking to every international media outlet interested to listen, sharing the evidence we’d verified of the state’s brute violence against peaceful protesters. When the regime began killing children under a total internet shutdown, seizing every opportunity to spread the truth felt like a moral obligation.

Frantic days and sleepless nights followed, especially as the regime crossed more red lines each day and instructed its foreign missions to keep tabs on those ‘tarnishing the image of the state’ abroad. I could live with the risk to myself, but I could never forgive myself if something happened to my family – who I couldn’t even warn due to the communications shutdown. If the regime did not ultimately collapse on 5 Aug 2024 due to international and public pressure, I may’ve had to live in exile for the foreseeable future.

After Sheikh Hasina was toppled, and an interim government comprising of human rights lawyers and technocrats who faced the brunt of her oppression came to assume power, for a brief moment, it felt as if the entire apparatus might finally be dismantled. Instead, we are now witnessing the same repressive legislation the Awami League once crafted and used to eliminate its opponents—being turned back against the Awami League itself. That is the perverse circularity of revenge politics in Bangladesh, and exactly what I mean when I say the master’s tools are being used to rearrange the house rather than dismantling it altogether. Ultimately, democratic renewal requires more than the removal of an autocratic leader. It requires undoing the architecture of repression instead of rebranding it. Authoritarian laws outlast authoritarian rulers, so we have to dismantle them.

Ultimately, democratic renewal requires more than the removal of an autocratic leader.

Can such systems ever fully reform from within? Sometimes they can start the process, but only if those in power are prepared to give up the very tools that protect them. Abolitionist thinkers distinguish between reformist reforms, which make a violent system more efficient or more palatable, and non-reformist reforms, which actually shrink its footprint and shift power away from it. The latter would mean repealing emergency style laws, removing exceptions to constitutional guarantees, repealing offences that criminalise dissent, and accepting meaningful oversight by independent courts and international bodies. In a Foucauldian sense, it is less about giving power away and more about breaking up the circuits through which power is able to operate and dominate.

In your research on reparations, how do ideas of remedy and redress either complement or challenge the traditional focus on punishment?

In international human rights law, the right to an effective remedy has traditionally been interpreted as having two complementary dimensions: a reparative dimension, which is about redressing the harm done to the victim, and a punitive dimension, which is about holding the perpetrator criminally responsible. In practice, however, the punitive strand often dominates domestic justice policy, and the reparative strand becomes all but forgotten. We celebrate a lengthy sentence of incarceration or even a death sentence, while victims lack the financial means to meet the costs of their victimisation (i.e. medical care, income support). My doctoral thesis seeks to unsettle that hierarchy. I am trying to bring together two groups of critics who share the same concerns, but are not necessarily in conversation with one another: the first are critical human rights scholars who warn that an uncritical embrace of incarceration as the primary means of enforcing human rights risks expanding the very coercive apparatus that often produces the violations in the first place. The second is abolitionist scholars who warn that contemporary systems of incarceration sit on the afterlife of slavery and colonial control, and that any account of remedy that centres prison will reproduce racial and class hierarchies rather than dismantle them.

To this end, my research attempts to answer the following questions. How can we build accountability for human rights violations without expanding the carceral state? To what extent can monetary reparation replace carceral punishment as the most effective remedy for most human rights violations, in support of the abolitionist and restorative justice movements? I will attempt to show how the under-theorisation of monetary reparation under international human rights law has allowed the punitive dimension of the right to an effective remedy to take centre stage in human rights protection. I will then query to what extent, if at all, the existing criminal justice system be repurposed to serve more reparative ends. There are interesting experiments in that direction, from practices influenced by Maori principles in Aotearoa New Zealand to restorative justice projects in the United Kingdom, where criminal proceedings are designed to facilitate restitution, apology and agreement on concrete steps to repair harm, rather than only to impose suffering on the offender.

So for me, ideas of remedy and redress both complement and quietly challenge the traditional focus on punishment. They complement it when criminal accountability is part of a broader architecture of support for victims. They challenge it when we mistake the suffering of the perpetrator as the only or primary measure of justice, instead of asking whether the people who were harmed have actually been helped to rebuild their lives and whether our response to atrocity is reproducing the same racialised and unequal patterns of confinement that abolitionist thinkers urge us to move beyond.

How has your time at Queen’s and Oxford shaped the way you think about international law and justice?

Being at Queen’s and Oxford has given me the space to connect the very immediate crises I was investigating on a day-to-day basis as a human rights lawyer with a much longer history of doctrinal debates about sovereignty, responsibility and reparation. It is also where I have learned to hold together two instincts that used to feel in tension: the urgency of speaking out during a crisis, and the discipline of thinking carefully about what international law can and cannot do.

Being at Queen’s and Oxford has given me the space to connect the very immediate crises I was investigating on a day-to-day basis as a human rights lawyer with a much longer history of doctrinal debates about sovereignty, responsibility and reparation. It is also where I have learned to hold together two instincts that used to feel in tension: the urgency of speaking out during a crisis, and the discipline of thinking carefully about what international law can and cannot do.

The seeds of abolitionist thought that were laid when I started my Oxford journey in 2022 when reading for the MSc in Criminology are now beginning to bear fruit as I embark on my DPhil. Being exposed to critical sociological and criminological scholarship forced me to question how the language of human rights has been used to expand the power of the state to arbitrarily punish individuals. This was not an easy realisation as it forced me to confront my own complicity in this process. That experience now sits at the core of my work on reparations and remedies.

Being able to benefit from fortnightly supervision meetings with a leading scholar of human rights and international law, Professor Başak Çalı, has also been central in shaping how I think about the role of international law in shaping just outcomes at both the national, regional and international levels. Each meeting has felt less like a stocktaking of progress and more like a calibration exercise. Our conversations have made me much more attentive to the diffuse and contested nature of interpretive authority in international law – how states, domestic and international courts, treaty bodies and the wider epistemic community of scholars all participate in giving meaning to human rights norms – and to the strategic possibilities that such interpretive pluralism opens up for my own reparations project.

Beyond formal supervision, Oxford is saturated with small intellectual “incubators” that continually reshape how I think about law and justice: the Bonavero Institute of Human Rights, where you are surrounded by practitioners and scholars trying to make human rights law usable in the real world; the Public International Law Discussion Group, which brings together international lawyers every week to debate ongoing crises from genocidal warfare to anthropogenic climate change; and countless talks, reading groups and seminars where people from very different ideological starting points test each other’s assumptions. At a time when social media algorithms increasingly trap us in echo chambers and reward confirmation bias, that kind of structured disagreement is a rare gift; Oxford has been one of the few spaces where I feel I can genuinely escape that confinement and have my views changed by serious engagement with people who disagree with me.

At a time when social media algorithms increasingly trap us in echo chambers and reward confirmation bias, that kind of structured disagreement is a rare gift; Oxford has been one of the few spaces where I feel I can genuinely escape that confinement and have my views changed by serious engagement with people who disagree with me.

At the same time, College life at Queen’s has been a reminder that questions about law and justice can never purely be technical. Conversations with peers from different corners of the world who do not study law but have experienced or witnessed some form of injustice constantly destabilise my assumptions and keep me honest about both the limits of law and how radically different people’s intuitions about justice can be, even when we are using the same vocabulary. At lunchtime you can feel fairly confident in your working hypothesis, and then have it quietly dismantled over dinner by a chemist who has never read a human rights treaty but can ask the most disarming questions.

At lunchtime you can feel fairly confident in your working hypothesis, and then have it quietly dismantled over dinner by a chemist who has never read a human rights treaty but can ask the most disarming questions.

Queen’s also has given me the opportunity to engage with a tight knit community of law students thinking about law at very different stages and from very different angles. I find myself talking to first-year undergraduates in the dining hall about what “justice” means to them at the start of their law degrees; debating with master’s students taking a module on investor-state arbitration and hoping to go into commercial practice about how protections for foreign investors can make ambitious climate regulation harder; and comparing notes with fellow DPhil students about which paradigms of justice they situate their research question in, and how it compares to my own conceptions of a just world.

Queen’s College Law Society also creates space for candid conversations with law Fellows who bring decades of teaching experience. Those conversations often turn into quiet reflections on how legal education has evolved in an increasingly globalised and digitised world – from teaching ancient Roman law to grappling with human rights, climate litigation, and algorithmic governance in the same tutorial rooms.

What do you enjoy about your studies at Queen’s?

Studying at Queen’s has quite literally been a lifeline for me. Right before coming here, I was doing my master’s in law at Harvard with a view to transitioning into the PhD. Yet when the Trump administration started relentlessly cracking down on international students while moving to revoke Harvard’s certification to host international students and Rumeysa Ozturk was abducted by masked ICE agents ten minutes away from me for simply co-authoring an op-ed, I had to seriously reconsider my initial plan. Life as a doctoral student thousands of miles from home was going to be taxing enough; could I bear the added burden of being dehumanised daily by a tyrannical regime? More importantly, could I live a life where I indefinitely suspend my right to free speech just to keep my visa valid?

Studying at Queen’s has quite literally been a lifeline for me.

It was in the middle of that uncertainty, during a class on injunctions against arbitrary presidential action, that the email arrived telling me I had been awarded a Clarendon Scholarship, partly funded by Queen’s. With less than a one percent chance of being nominated and then selected, it was not an outcome I had allowed myself to expect. When it came, it felt like a door opening out of a situation that was becoming untenable. The fact that I can now focus on my DPhil full-time, rather than juggling multiple jobs just to pay rent, is a huge privilege—especially when so many international doctoral students do not have that safety net.

That experience colours how I see Queen’s and Oxford. It reminds me that being here is never just about individual merit; it is also about visas, funding, and political decisions far beyond any student’s control. It is why I feel a particular responsibility to support Queen’s outreach work with school students from under-represented communities as an Outreach Facilitator. The first law taster session I designed for a group of Year 11 students was, by coincidence, scheduled for the morning after the Hasina verdict. On what was meant to be a quiet Sunday, I spent the afternoon briefing international media about due process violations in a crimes against humanity trial in Bangladesh, and that evening I was crafting problem questions to demystify law for teenagers who might never otherwise picture themselves at Oxford. For me, those things belong together: justice is not only about judging past abuses; it is also about widening who gets to study, practise, and shape the law in the future.

On what was meant to be a quiet Sunday, I spent the afternoon briefing international media about due process violations in a crimes against humanity trial in Bangladesh, and that evening I was crafting problem questions to demystify law for teenagers who might never otherwise picture themselves at Oxford. For me, those things belong together: justice is not only about judging past abuses; it is also about widening who gets to study, practise, and shape the law in the future.

Oxford as a whole is a vast, decentralised ecosystem, and it can feel overwhelming and, at times, lonely. That is where the community at Queen’s gives me a sense of home. The College is small enough that you keep running into familiar faces in its medieval hallways, but large enough to feel genuinely international. I love that I can choose between the warmth of the MCR’s leather sofas, the Upper Library—with its long wooden desks, high windows and quiet sense of history, which I am tempted to claim is the most beautiful reading room in Oxford—and, when the weather cooperates, the stillness of the Fellows’ Garden.

The College is small enough that you keep running into familiar faces but large enough to feel genuinely international.

For someone working on egregious human rights violations and reparations, being part of a College culture where intellectual seriousness sits alongside a strong welfare ethos makes it much easier not to burn out. That is what inspired to join the MCR Committee as a Welfare Officer, and I have thoroughly enjoyed hosting weekly welfare events that bring overworked graduate students to decompress over fun activities. Last Saturday, I was co-hosting a Middle Eastern brunch where the conversations drifted from what would comprise the best fillings for falafel wraps to whether reparations programmes for historical injustice are economically viable, or whether large-scale debt cancellation would do more for justice than traditional compensation schemes. I also enjoy how movie nights often spill over into arguments about diagnosing the causes and consequences of structural injustice, and I like that those shifts feel natural rather than jarring. One of my favourite evenings this term was hosting two friends from completely different disciplines and other colleges (with less generously endowed MCR facilities!) watching the Chomsky–Foucault debate: the first half dense with technical philosophy and linguistics, the second half turning on questions of power, punishment and law.

What I enjoy most about my studies at Queen’s is precisely that blend: a place where I can think seriously about mass atrocities and reparations, feel supported as a human being, and be constantly reminded—in hall, in the library, in the MCR—that justice is not an abstract ideal but something that shapes, and is shaped by, people’s lives.

If you could remind the world of one enduring principle of law, what would it be and why does it matter beyond this single case?

If I had to choose one enduring principle, it would perhaps be due process. For me, due process is not only something any defendant is entitled to as a matter of law, it is also a debt we owe to victims, especially those of mass atrocities. People whose family members have been unlawfully killed or those who have been maimed for life due to an act of brutality deserve a process that establishes guilt in a way that cannot later be questioned, either on the day of the verdict or a decade from it. An expedited trial which sidesteps due process safeguards may satiate populist sentiments in the short term, turning the verdict into yet another battleground where what happened is constantly questioned and victims are forced to defend their own suffering again and again. If a verdict has to stand the test of time, it must first pass the test of due process.

Due process is not only something any defendant is entitled to as a matter of law, it is also a debt we owe to victims, especially those of mass atrocities.

Taking this simple yet deeply unpopular position has not been easy in the Hasina case. After my recent media interviews, I have received a barrage of hostile comments simply for suggesting that she is entitled to fair trial rights: accused of being a hypocrite, traitor, a paid foreign agent, a sympathiser, an imbecile and Hasina Mitläufer. The irony is that many of the same labels were thrown at me by Awami League supporters when I exposed abuses by her government. That is the paradox of human rights work. I wish the people maligning me now understood that the safeguards that protect an unpopular defendant today are the very same safeguards that could stop a future government from using the law to punish innocent dissidents tomorrow. That is why the essentiality of this legal principle extends far beyond any single case or country.

Fresh from the Fringe, writer Oisin Byrne (English & Spanish, 2021) and director Eva Bailey (English & French, 2021) reflect on taking meta-comedy Unprofessional from a sold-out Oxford run to the Edinburgh Fringe. Unprofessional playfully satirises actors, audiences, and the industry, while holding onto the real graft behind the craft.

In this Q&A, the writer/director duo talk influences, auditioning for “carnage,” and what they learned from different audiences each night.

Can you describe the Fringe in three words?

Exciting, unforgettable, hilarious!

Oisin

Unpredictable, riotous, incredible.

Eva

Your play, Unprofessional, pokes fun at actors, audiences, and even itself. What first sparked the idea?

Oisin: I’ve always loved media which satirise the people who make that media in the first place: plays like The Play That Goes Wrong and Noises Off, TV shows like 30 Rock, and films like Singin’ in the Rain and Hail! Caesar. It was only once I studied a Modern and Contemporary Theatre paper in my fourth year that I saw the potential for this being taken to darker, more form-breaking places, with plays like The Writer by Ella Hickson and The Author by Tim Crouch. Unprofessional is an attempt to marry a more satirical, light-hearted approach with some darker experimentalism – we wanted audiences to feel genuinely disturbed by the prospect of the play they are watching genuinely falling apart, before laughing at the eventual realisation that everything is intentional and scripted.

Guy, your protagonist, is both hilarious and tragic. How did you balance comedy with an honest take on the struggles of being an actor?

Oisin: This wasn’t too difficult, as most of the day-to-day situations experienced by an actor are kind of ridiculous when you strip them out of context. Things like auditions, self-tapes, shoots for yoghurt adverts, and community theatre are ripe with comedic potential. I also have quite a few friends I met at uni who are entering the world of acting (including one who I lived with last year), and so being around them helped with some inspiration. Thankfully none of them are anything like Guy, though: he’s more of an amalgamation of all the worst things I’ve heard about other actors, whether it be amateur level or Hollywood.

Eva: In terms of staging the play, striking that balance was helped enormously by our wonderful cast. During rehearsals on the lead-up to Edinburgh, I worked a lot with Aaron (who played Guy) to draw out Guy’s exasperation that everything around him is falling to pieces. I really wanted Guy (and later on in the play, Aaron himself) to feel like a real person – he is, largely, a caricature, but I think both the comic and tragic elements of the play hinge on audiences believing that this is an actor who truly cares about the work he’s doing, even though a lot of it is of questionable quality. Sure, Guy’s a diva, but he’s a diva with a genuine passion for his craft: although much of the script is very tongue in cheek, I think Unprofessional still sheds light on how much actors have to graft to break into “the industry”.

You’ve cited Tim Crouch and The Play That Goes Wrong as inspirations; how did their influence show up in your process?

Oisin: When I began writing the play, it was going to take a much darker route, and so the Tim Crouch influence was stronger initially. His play The Author places the audience on either side of a writer and group of actors who describe the unusual and eventually horrifying process of putting on a particularly dark play, and implicates the audience very much in all of this through a Q&A style structure. From there, I was intrigued by audience culpability, but particularly within the realm of amateur theatre. If an audience member sits down to watch a student play and it turns out to be genuinely woeful, falling apart due to a lack of rehearsal, forgotten lines, and temperamental actors, what should they do? Do they stay to relish in the failure? Do they fake a coughing fit to escape? Or do they heckle to break the barrier between them and the actors? With amateur theatre, these questions are inherently more present in an audience member’s mind, and so I wanted to force audiences to confront them by staging a play that, initially, appears to be genuinely going wrong.

However, as I started writing some scenes – in particular, a scene where Guy has a breakdown and hallucinates Matt Damon – I realised that the whole thing didn’t have to be dark and uncomfortable like Crouch’s theatre. So I wrote Unprofessional such that, while the first few staged events of the play ‘going wrong’ may seem credible and create an unsettling atmosphere, these mistakes become gradually more ridiculous and comedic. This way, the whole audience is guaranteed to be onside with the play’s central conceit by about halfway through, and experience a journey from the discomfort of plays like Crouch’s towards the slapstick farce of shows like The Play That Goes Wrong.

Eva: One of our biggest challenges when approaching Unprofessional from a directorial standpoint was how on earth we were going to run auditions that tested an actor’s suitability to deal with genuine carnage onstage. Like The Play That Goes Wrong, the vast majority of Unprofessional is tightly scripted, but we wanted the moments that went “wrong” to be as believable as possible, particularly in the opening scenes. There are several moments, too, where Unprofessional asks actors to think on their feet and improvise – I’m thinking in particular of a scene towards the end of the play, where one of the actors is so woefully anxious that they are turfed offstage and replaced by an unsuspecting audience member. So, when we were running second round auditions after receiving a wealth of brilliant self-tapes, I realised we needed to replicate the carnage of the play “going wrong” in the audition room itself. We asked actors to perform monologues while being interrupted at various moments by weird noises, we set off phone alarms in the middle of poignant moments, and almost all of the auditions ended up with me chasing actors around the room while they attempted to perform a scene (which sounds much stranger than I intended now that I’m typing it out…I promise everyone was on board!). Although unconventional, the audition process produced some real improvisational gems, and ended up closely mimicking multiple scenes in the play – and, it goes without saying, we cast four brilliant actors who took the weirdness of it all in their stride.

The play is described as “meta-comedy.” What does that mean for you, and what should audiences expect?

Eva: We had a great review from UK Theatre Web that I think perfectly describes the audience experience of watching Unprofessional. The reviewer said that he was confused and ready to walk out after the first few lines, but before he knew it the show began twisting and turning in new directions, with hilarity and chaos growing in equal measure, until he was laughing out loud and fully onboard with the absurdity of it all. Having watched the play over 25 times now, I still love the moment in every performance when the audience breathes a sigh of relief that everything was planned all along.

I still love the moment in every performance when the audience breathes a sigh of relief that everything was planned all along.

Oisin: ‘Meta’ can often be a bit of a contentious and vague label to slap onto something, but I love it because of how wide the scope is. Unprofessional is ‘meta’ in many senses; firstly, in that it refers to itself as a performed piece, being a play about itself going wrong; secondly, in that it’s a piece of theatre about the act of making theatre; and finally, in that the play’s superficial narrative before anything ‘goes wrong’ explores Guy, a character trying to make it in the theatre industry.

The play had a sold-out run in Oxford; what did you learn from that experience that you took to Edinburgh?

Oisin: The Oxford run was super fun, and thanks to great audience numbers and reviews we got to learn really important things about the show. On different nights, the penny-drop moment – when audiences realised that everything they were watching was scripted – happened at different points. Larger, younger audiences often felt more comfortable laughing through purposefully awkward moments, and so the tone of the play shifted towards out-and-out farce more quickly on those nights. I think learning to lean into the riskiness of the show, and embrace that every night was going to be very different, was one of the key things we took to the Fringe. Once we did this, some hilarious stuff started happening that even we couldn’t have predicted – one night a Front of House member at our venue was in the audience, and at the (very-much scripted and planned) moment when Eva walks in late as a ‘disruptive audience member’, he started having a go at her and trying to usher her out of the theatre, not realising it was part of the show! Watching our actors improvise with that and seeing him realise that he had become embroiled in the chaos was one of my favourite moments of the whole festival.

Learning to lean into the riskiness of the show, and embrace that every night was going to be very different, was one of the key things we took to the Fringe.

Eva: As Oisin says, it was just great to have so much feedback, and so many wonderful reviews. The Fringe is a beast – there were almost 4,000 shows there this August – so to have pre-made marketing material that we could use to get bums on seats in Edinburgh was also priceless. We also took on board suggestions from friends and reviewers to help improve the show; the great thing about working on new writing is that you have licence to change the script as and when you like so, even in Edinburgh, our wonderful cast were able to make tweaks every night to refine the show right up until the end of the run.

Production photos by Coco Cottam

Oxford has such a strong student theatre scene. How did that environment shape you both?

Eva: I headed straight for the OUDS stand when I visited the Freshers’ Fair back in my first year: I was brought up on a diet of amateur theatre, so I knew that I wanted to continue performing on stage when I came to university. I successfully auditioned for my first musical (Sweeney Todd at the Oxford Playhouse) in Freshers’ Week, and since then I’ve been lucky enough to perform in so many fantastic productions. Some of my favourite roles include Audrey in Little Shop of Horrors in the first Queen’s College Garden Musical post-pandemic, Olive in The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, once again at Queen’s, and Cinderella in Into the Woods at the Oxford Playhouse again, the opening performance of which was just two days after I submitted some of my coursework for my English finals.

What I didn’t expect, however, was the passion I’d gain for working behind the scenes while at Oxford. The amazing thing about drama here is that there is just so much of it – there are at least four shows happening every week during term-time, which naturally generate an enormous amount of opportunities. Buoyed by talented friends, and itching to put my screen time to good use, I’ve also dabbled in marketing shows: I was the co-marketing manager for Oisin’s first play, Blue Dragon, and last year, I marketed the OUDS National Tour of The Taming of the Shrew. When Oisin told me about Unprofessional, I knew that it would make a fantastic first venture into directing, and I’ve loved every second of it. Although he won’t tell you this himself, Oisin truly is a fantastic writer, and it’s been such a joy to work with him on bringing his script to life. The opportunities I’ve been afforded within the Oxford drama scene are unique, and utterly priceless – where else can you submit your idea for a play two minutes before the deadline, then put it in front of paying audiences just a few weeks later?!

The opportunities I’ve been afforded within the Oxford drama scene are unique, and utterly priceless – where else can you submit your idea for a play two minutes before the deadline, then put it in front of paying audiences just a few weeks later?!

Oisin: Eva was definitely a lot more into theatre than I was when we both started at Oxford. It was thanks to making friends with her (through studying English together at Queen’s) and other theatre-y people at Queen’s that I was introduced to the world of OUDS (Oxford University Drama Society). Even then, my involvement only stretched as far as hearing about shows and going to see my friends perform until Trinity of my second year, when I was Assistant Director of the Queen’s Garden Musical, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee. Aside from being in the ensemble of a couple shows at school, that was my first full foray into theatre, and I absolutely loved it! It helped that, being a Queen’s show, it was directed by one of my good college friends, Harry, as well as having Eva and many other friends on the cast and crew. Doing such a light-hearted show with wonderful people gave me a great introduction to the world of student theatre, and so early in the rehearsal process I felt comfortable enough to share an idea for a play I had with Harry. He encouraged me to write it so that we could put it on together, and that became my first play, Blue Dragon! That way I ended up going from zero involvement in theatre to doing two shows within the space of a few weeks. Now, I can’t imagine my time at Oxford without doing theatre.

How did you balance theatre and your academic work?

Oisin: I was fortunate enough to work on two shows during Trinity of second year, probably the least work-heavy term of my entire degree, then write another show during my year abroad when I had lots of free time, and finally work on another couple of shows, including Unprofessional, in my final year. This meant that I only really had to contend with this balance in Michaelmas and Hilary of fourth year, though this was admittedly difficult given that I had three pieces of English coursework due over the same course of time as writing, rehearsing, and putting on Unprofessional. I won’t say I always managed a good balance, but I stayed relatively on top of things by keeping academic work to daytime and weekdays, and any playwriting or show admin to weekends and spare pockets of time here and there. When it came to rehearsing Unprofessional, it really helped having Eva alongside me, and our friend Luke (also Queen’s!) producing. Not only are Eva and Luke organisational wizards experienced in all things theatre, but we all studied Modern Languages so our timetables were pretty similar, meaning we were able to coordinate putting the play together in just under three weeks during the middle of Hilary term. This was also thanks to our extremely lovely and co-operative cast, who brought energy, commitment and fun to rehearsals, meaning we never had to stretch ourselves too much time-wise.

Eva: Much to the initial dismay of some of my tutors, I dived head-first into theatre at Oxford, and was involved in at least one show per term from the moment I arrived. However, despite having professional ambitions in the theatre industry, I firmly believe that student theatre should remain a fun addition that complements a degree rather than detracts from it. I was the Access and Outreach Rep for OUDS during my final year, fuelled by the conviction that good student theatre can be put on without taking over your life, if students (particularly those who haven’t had access to much theatre pre-university) are given the tools and the knowledge necessary to create a show. Theatre is a space of play – we are literally playing pretend in front of other people – and I always tried to remember that in the moments when it started to feel stressful. In terms of Unprofessional, as Oisin says, it worked because we were such a good team. We also had our friend Luke producing the show for us in Oxford, and we were able to enlist various friends to do marketing shoots and help us with the lighting and sound design, which made the whole thing a million times easier. I’m kind of looking forward to talking to Oisin about things other than budgets and air beds and easels to hold giant posters of Matt Damon and Paul Rudd, though!

Theatre is a space of play and I always tried to remember that in the moments when it started to feel stressful.

What’s next for you?

Eva: I’m very lucky to be coming back to Oxford in October to pursue a Master’s in French, with a focus on French theatre in particular. It was while Oisin and I were studying a contemporary theatre paper together in our fourth year that I realised I wanted to continue delving deeper into the theatre world academically, and I haven’t (yet!) had chance to do so from a French perspective, so I’m really looking forward to it. I have a particular interest in the practice of theatre translation – which was the topic of my undergraduate dissertation – so I’d love to work on translating one of the French plays that I love in the near future. I’m still not entirely sure of the exact direction that my career will take, but it will certainly be theatrical in some capacity.

Oisin: Aaaarrgghh. Very scary. To be honest, I’ve spent so much of the last few months thinking about and preparing for finals, and then the Edinburgh Fringe run of Unprofessional, that I haven’t devoted as much time as I’d like to applying for jobs or preparing for the future. I’m keeping myself busy and financially afloat with a couple of part-time jobs while applying for things. In terms of playwriting, I don’t want it to just stop there, so I’m sending the script of Unprofessional to some smaller theatres in London, as well as looking at some playwriting residencies. I’ve also just begun writing my first full-length play, which, once it’s done, I can hopefully send to theatres too. I’m not too concerned or naive about immediately being able to enter a career in theatre, so I’m happy to make a living doing anything else for a while, and perhaps eventually save up for a Master’s in Playwriting.

Can you recommend a play or show (other than Unprofessional of course!) that has stayed with you in some way / contributed to your love of theatre?

Oisin: I’m obsessed with so many shows and writers, but if I had to stick to one I’d say Appropriate by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins. I studied it in my fourth year, and while it might not have had a direct influence on my writing, to me it’s the perfect modern play. It’s a beautiful read due to Jacobs-Jenkins’ command over prose in his stage directions and his depth of character, but it’s also incredible to watch because of the stunning sound design and disintegration of the set built into the script. It’s also a devastating, unsettling comment on American race relations, guilt, and collective ignorance, all whilst being outrageously hilarious. Jacobs-Jenkins has a unique ability to let very dark themes and brilliant comedic moments exist alongside each other in his plays, so for that reason I’d recommend Appropriate or anything else he’s written. Also The Book of Mormon and Into the Woods.

Eva: I’m going to indulgently allow myself to pick three shows (though this list could easily go on forever!). As a musical theatre lover first and foremost, I have to mention Shrek The Musical. It was the first musical I ever saw live, because it came on tour to Birmingham, and I can just recall the warmth that spread through my chest when Shrek, Donkey, and Fiona hit the gorgeous three part harmony at the end of the first act. It might sound like a silly premise for a show – and it definitely is – but Shrek is genuinely a fantastic musical.

A show that I think about frequently is Moderation. It was the first show I saw at the Fringe in 2023, when I was up performing with the new musical Dead Man’s Suitcase, which started life in the same Oxford theatre as Unprofessional. The show was about Facebook moderators, who were (and in many cases still are) forced to watch content that is flagged as inappropriate by users which – as you might imagine – is often brutal and deeply troubling. The show was just impeccable, and it made me realise what a special place the Fringe is – I got to see that show for free on a random Friday at 4pm. As I’m about to embark on a year of studying French theatre, it would be remiss of me not to mention something French. A French play that stayed with me is Joël Pommerat’s Contes et Legendes, which I saw in Paris during my year abroad. Ostensibly dealing with adolescence and coming-of-age, it made me think a lot about bodies on stage, because you had women playing men who were themselves playing robots. That layering is fascinating to me, and forms a large part of what I want to unpack in the year ahead.

Step inside the Queen’s Library and you’ll find more than just books: you’ll discover a building with layers of character. In this blog, three students take us on a journey through their favourite corners of each level, as we explore the hidden personalities of the College Library. From peaceful hideaways to sunlit study spots, every floor has its own charm. Which one will be your favourite?

The New Library (basement level) with Audey Kang, MSc in Clinical and Therapeutic Neuroscience & Tayo Dada, MSc in Public Policy

In three words, what’s the vibe?

Tayo: Vibrant, bright, and motivating.

Audrey: Cozy, convenient, conducive (to locking in).

What’s the thing you love most about studying there?

Tayo: The atmosphere in the New Library has incredibly energising quality that’s absolutely contagious. There are times when I arrive feeling completely exhausted but seeing so many students deeply focused on their work and studying motivates me to study too.

Audrey: The convenience! Second screens make doing work so much more convenient (I have never had a monitor before, so this is life changing), and having the toilets and water refill on the same floor makes working for long periods of time easy.

Do you have a “go-to” seat or hidden corner that’s your secret study haven?

Tayo: I love sitting right by the monitors and directly under the skylights where I can look up and see the sky and trees above.

Audrey: It’s just any seat with a second screen, but usually the one second from the left. It’s also funny because I often end up sitting next to the same people, so coming in and waving hi before opening my computer can feel a bit like clocking in for a shift.

Why does it suit your study style or personality?

Tayo: It suits my study style because I thrive in high-energy, well-lit environments. The combination of natural light from the skylights above and the vibrant atmosphere created by the students keeps me alert and engaged. It’s hard to doze off here even when you are extremely tired.

Audrey: I think it’s common to come to Oxford from America with this whole dark academia thing (reading Babel probably helps), but the truth as a neuroscience student is that squinting at your code and graphs on your laptop in the Upper Library just doesn’t work as well as having a second screen. Also, I very much do most of my work in the evening, I’m a night owl, so I prefer not to know the passing of time, and I feel like you get the most isolation from that with the bright lights of the New Library. I do love the skylight though and being able to see the weather changes, from a thunderstorm and lightning one day to sunny blue skies the other. Coming from California, I always find a rainstorm exciting.

What’s unexpected about this space?

Tayo: What really surprises me is just how extraordinarily quiet this level is. I know libraries are supposed to be quiet spaces, but this floor is really quiet compared to other levels where you can easily hear footsteps, people moving around, and the constant sound of students going up and down the stairs.

Which library level do you think would surprise prospective students the most, and why?

Audrey: Definitely the Upper Library. It’s completely different in feeling than the rest of it, and the coolest part of it is that it existed first and the rest of the library was built underneath it, which I think is an insane architectural and conservational feat.

Any memorable moments while studying in the library?

Tayo: One of my memorable moments in the library was when my friend Julia came to study with me. It was at the peak of assessment season. Having her company made what could have been a stressful time much more enjoyable – we shared silly jokes between study sessions and captured the moment with plenty of photos.

I also have fond memories of randomly running into my flatmate Audrey while we were both studying. We’d secretly snap photos of each other looking intensely focused and send them to our other flatmate in our group chat.

Audrey: My friends and I all have very different study habits. They really like the Upper Library but it’s still great to have them close by because I can ask one of them for hand cream if my hands are dry and they’ll run down from the Upper Library and I’ll run up from the New Library and we’ll meet in the middle in the Lower Library!

The Lower Library (ground level) with Mari-May, First-year BA in Chinese

In three words, what’s the vibe?

Intimate. Timeless. Warm.

What’s the thing you love most about studying there?

It’s the perfect blend between the dark academia aesthetic true to Oxford, and functionality. The window grillwork is gorgeous, and if you are doing some light reading then the armchairs are mega comfy. Also, I’m a night owl, so it being open 24/7 is a blessing.

Do you have a “go-to” seat or hidden corner that’s your secret study haven?

The Sanskrit Desk in the very back corner of the library is my absolute favourite.

Why does it suit your study style or personality?

It is sandwiched in between the shelves for Asian Middle Eastern Studies. As an AMES student, it’s very handy to just be able to lean back in my chair and grab a book. Also, it is probably the most isolated spot, which helps with my abysmal attention span.

How do you make the space your own?

All of my stationery is either pink or glittery, and I make sure to set up the desk all cute. Music is a necessity, and I usually listen to the Final Fantasy video game soundtracks while studying!

Any memorable moments while studying in the library?

Once, I left my desk to fetch a book and my headphones disconnected. Music blasted from my laptop in the middle of the library. No one could figure out how to turn the volume down using the keys, so they had three people faff about on the laptop trying to turn it off. When I returned one of my friends relayed the happenings with much amusement. It was so embarrassing I couldn’t go back for a week.

The Upper Library (first floor) with Mads Proitz, DPhil in Classical Archaeology and Klara Zhao, MPhil in Egyptology

In three words, what’s the vibe?

Mads: Historic, inspiring, subdued.

What’s the thing you love most about studying there?

Mads: The atmosphere and aesthetics are second to none. I can always count on it to be a nice and quiet study space, and the occasional creaking floor fits the mood nicely. It feels secluded enough so that you can easily forget that you’re in there with other readers.

Klara: It can be a silent haven: with large desks and comfy red leather chairs, and almost total privacy between the booths formed by those thick wooden shelves.

Do you have a “go-to” seat or hidden corner that’s your secret study haven?

Mads: Any of the nooks are lovely, but if I can choose a nook that has a view of either one of the globes or the orrery, that is a bonus just for the visuals of it.

Klara: The desk on the east side of the orrery has always been my favourite: the orrery blocks the view of the person opposite and instead you have a fine view of the golden Apollo in the ceiling plasterwork overhead.

Why does it suit your study style or personality?

Mads: I often study at home when I know the Upper Library’s opening hours won’t suit my own study hours and this because a lot of the larger libraries can feel crowded or busy. I prefer to work in a dead silent area where you 1. Have room to spread out all your books and writing material, 2. Can enjoy privacy when studying: I get very self-conscious if I know that someone can see my screen/writing. I am also doing a DPhil in Classical Archaeology, so I think my love for old and historic spaces comes with the territory.

How do you make the space your own?

Mads: I like to lay out my books, laptop, and notebooks across the desk and put on a quiet playlist without lyrics/voice.

What’s unexpected about this space?

Mads: I might be spoiled at this point, but many of the guests I’ve brought in to unashamedly show off our library for have been impressed and surprised that we are allowed to use the space actively.

Which library level do you think would surprise prospective students the most, and why?

Klara: The Upper Library is stunning but the New Library has its own Egyptology library (the Peet), which lies behind some canopic jars, and that might well be a bit of a surprise for some.

Any memorable moments while studying in the library?

Mads: All study sessions in the Upper Library are memorable 🙂

Klara: Duckling day! On 9 May 2021, a mother and her ducklings entered College and made their way into the New Library through the entrance that had been opened up on account of the Covid-19 one-way policy. A very exciting time for us all, and a refreshing revision break.

Header images: Fisher Studios

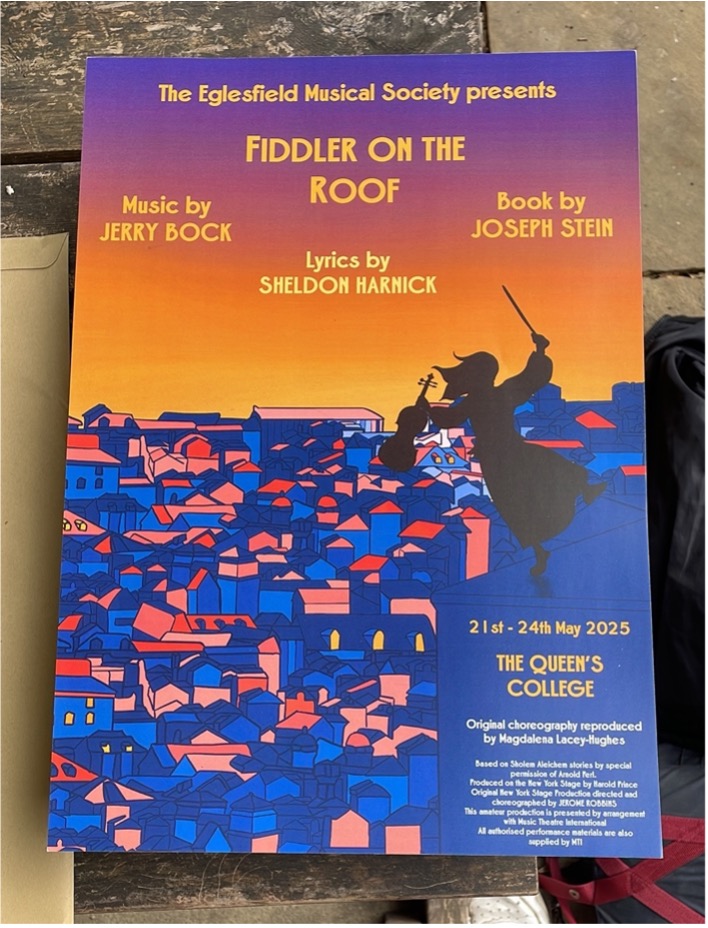

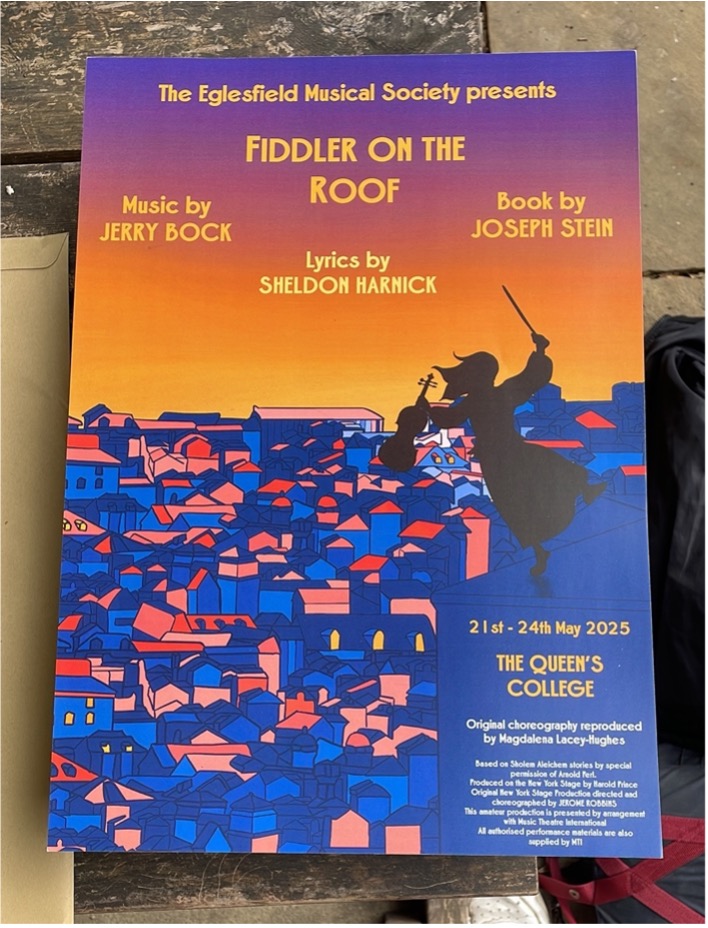

The Eglesfield Society’s summer show is an annual highlight in the Queen’s Trinity Term calendar of events. This year, the College gardens provided the backdrop for Fiddler on the Roof. This student-led production brought together around 70 students from across Oxford, including visiting students from the US, with a diverse and enthusiastic cast and crew drawn from over 15 colleges. Producer Matilda Bates tells us more.

This year the show was Fiddler on the Roof, a beautiful and timeless story about the struggles of a Jewish community in 1905 Tsarist Russia to reconcile tradition with change, amidst growing threats of violence and displacement. We felt this was an important story to tell in today’s international climate, and the gardens of The Queen’s College provided a perfect location.

Putting on a production of this scale is a massive undertaking. The show was entirely student-led, relying on the talent and skill of the student community. Around 20 members of Queen’s were involved as members of the cast, production team, and band, and we also collaborated widely across the University. Our directing team came from Trinity and Magdalen, and the cast included students– both undergraduate and postgraduate– from over 15 different colleges. We were also delighted to welcome several visiting students from the US. For some of our company, this was their first experience of putting on a musical, while others were seasoned performers and technicians. Altogether, nearly 70 students were involved, making it a large collaborative effort across the University.

The show required lots of time and effort over Hilary and Trinity terms. We rehearsed throughout the second half of Hilary, then had an intense week of rehearsals in 0th week of Trinity known as bootcamp, where we put together the big numbers with music and choreography. Everybody worked so hard and we all had so much fun – it was a great opportunity for the cast to really get to know each other. Another highlight of the process was the sitzprobe, where the cast and band met for the first time to sing through the show. It was amazing to hear everything come together, leaving everybody excited for show week.

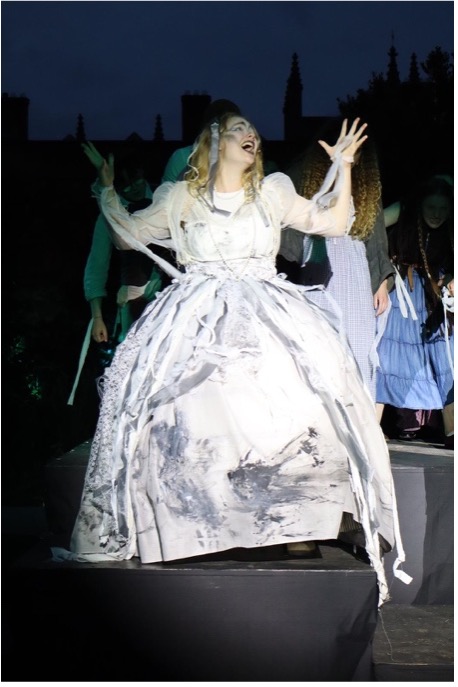

Show week was the busiest week of my time in Oxford. Preparing for the show was a full cast and crew effort: unloading and constructing staging and tech, setting up the garden, transporting costumes from the National Theare, and transporting props across Oxford on a trolley (we got some funny looks from members of the public!). People had so many skills, and they were all put to great use. For example, one of our cast members is an excellent seamstress and made a beautiful dress for Fruma Sarah to wear in The Dream (pictured below). Our tech team, crew, and publicity team were all absolutely excellent, and every person was an invaluable member of the team.

All five performances were a triumph. The staging and lighting looked beautiful in the garden, and it got dark as we went into the second half, making the lights even more striking. We made record ticket sales thanks to our incredible publicity team, having to run to find more chairs because it was so crowded! We were reviewed by a number of student publications and received high praise: the choreography especially receiving frequent commendation. The threat of rain loomed all week, but thankfully it held off until the final performance. The rain was light enough that we could continue, and it added a level of poignancy and drama as the story reached its climax, so worked nicely. Overall, we had an incredible reception from our audiences, which made our hard work seem extremely worth it!

I want to extend huge thanks to everybody who supported the production. First, thanks to the generous support from funding bodies, especially to the Walter Pater Grant, the 650th Anniversary Trust Fund, and Queen’s JCR Arts Fund: their support made this production possible. Second, massive thanks to our director, whose creativity and dedication brought the show to life, alongside taking her finals! Thanks to the amazing tech team, who made everything run so smoothly. And finally, thanks to everyone at Queen’s who made this happen: Sarah Daley, the Conferences team, and the Lodge for making everything run so smoothly. We all had the best time bringing this beautiful story to life: it was an experience we’ll never forget!

Matilda Bates

Exec team

Director: Hannah Davis

Assistant director: Phoenix Barnett

Choreographer: Magdalena Lacey-Hughes

Co-musical director: Kyle Siwek

Co-musical director: Tom Constantinou

Producer: Matilda Bates

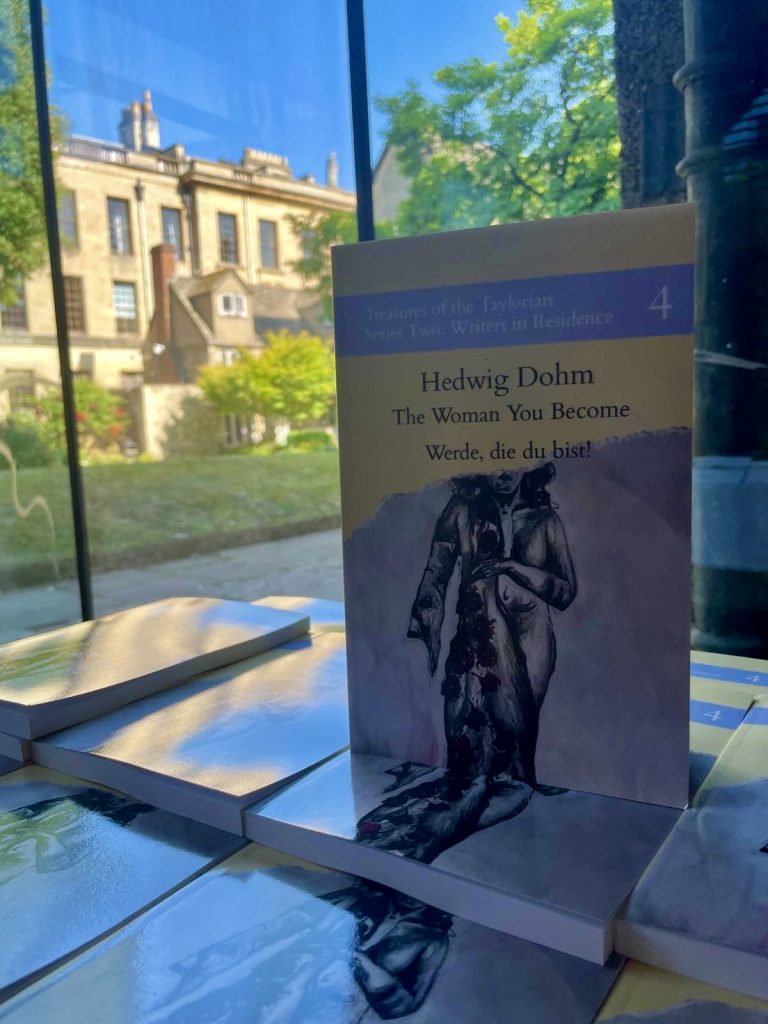

In Hilary and Trinity terms of 2025, the second-year students in German worked on a collaborative translation of Hedwig Dohm’s novella Werde, die du bist! (1895), edited by their tutor Marie Martine.

It was published as a bilingual edition by the Taylor Editions as part of its Writers in Residence series. More information on the Taylor Editions and the translation. We asked them about the process.

Questions for Marie

What drew you to this particular nineteenth-century text?

I discovered this text during my DPhil on women’s writing at the end of the nineteenth century in Germany, France, and Norway. Hedwig Dohm (1831-1919) is a fascinating figure: despite having received a limited education, she actively participated in Berlin’s intellectual circles and eventually established herself as a prominent essayist. Her feminist essays respond to contemporary misogynistic discourses that argued that women cannot participate in the public sphere without putting themselves and society in danger.

This text is interesting not only for its political resonance but also for its poetic quality.

Her fiction adopts a more pessimistic stance, describing the constrained lives of contemporary women struggling to liberate themselves from social expectations. Her novella Werde, die du bist! (which we translated as ‘The Woman You Become’) was published in 1895 and tells the story of Agnes Schmidt, a widow who tries to find herself after a life of sacrifice as a wife and mother. This text is interesting not only for its political resonance but also for its poetic quality. Agnes writes about her connection to the natural world and her existential interrogations in a beautiful and sometimes complex prose. Dohm’s fictional writing has only been recently rediscovered by feminist scholars, but it has its place among other canonical nineteenth-century texts. It was an honour to edit a collaborative translation of this text aiming to give it a contemporary resonance and to make it accessible to English-speaking readers.

What’s unique about translating literature in a collaborative environment?

Translation is often perceived as a solitary activity, especially within the university context where students typically complete their assignments independently and are assessed through individual exams. But translation can also be a dialogue: a dialogue across time between a writer and a translator, a dialogue across cultures and languages, and it can also be a dialogue among translators. Collaboration sparks creativity: when a student was stuck on a sentence, a paragraph, they could always count on the discussions in class to come up with creative solutions together. Collaboration can also carry a political dimension: as we worked together to convey Dohm’s political message, we reflected on what it means to collaborate on a translation. At times, our discussions flowed smoothly; at others, they became more animated, as students passionately defended their interpretations. Yet the shared goal remained consistent: to reach a compromise that reflected the collective voice of the group and do justice to Dohm’s own feminist project.

Collaboration sparks creativity.

Were there moments where the students’ perspectives changed the way you saw the text?

Translating this text with a group of four brilliant students reminded me, again and again, of the poetic quality of this text. In my research, I mostly focus on Dohm’s political message and her dialogue with contemporary discourses on womanhood. But witnessing how the students tried to convey the fluidity and the beauty of Dohm’s descriptions was a reminder of Dohm’s unique style and how she plays with language to convey her message. We hope to have conveyed the evocative power of Dohm’s style through our creative translation.

Questions for the student translators

What does it mean to have the work published in the Taylor Editions Writers in Residence series and go into the Queen’s College library?

Emily Dicker: When I first applied to Oxford, I would never have dreamed that I’d be a published author by the end of second year! It’s been amazing to work on this project over the last two terms and see how translation, which is often seen to be a somewhat mechanical exercise confined to the classroom, can be brought to life in an extremely creative process with very concrete results. We’re very lucky that the Taylor Editions’ Writers in Residence series makes this possible and, although I still can’t quite get my head around it, it’s going to be so exciting to see our names among the authors we study in the Queen’s library!

When I first applied to Oxford, I would never have dreamed that I’d be a published author by the end of second year!

How do you hope readers, or future students, will engage with this edition?

Emily Dicker: Predominantly, I hope it will serve as a huge source of inspiration for the fun which can be had by doing a Modern Languages degree at Oxford. But I also think it’s amazing to have a bilingual copy of this incredible text so that it becomes more accessible to all readers, and not only those who understand German. It would be amazing if, as a result, readers gained a new favourite book which would otherwise have been inaccessible to them or even if, upon reading the German and English in parallel, they were inspired to learn a bit of the language for themselves.

I hope it will serve as a huge source of inspiration for the fun which can be had by doing a Modern Languages degree at Oxford.