Some names of College Members have been absent from the memorial since it was installed in 1921: four from the Central Powers and one from Warwickshire, who died from his wounds some time after the war’s end. To complete the College’s remembrance of all its members, and in the spirit of international reconciliation, these names are now being added.

This exhibition provides further context and details of their time at the College.

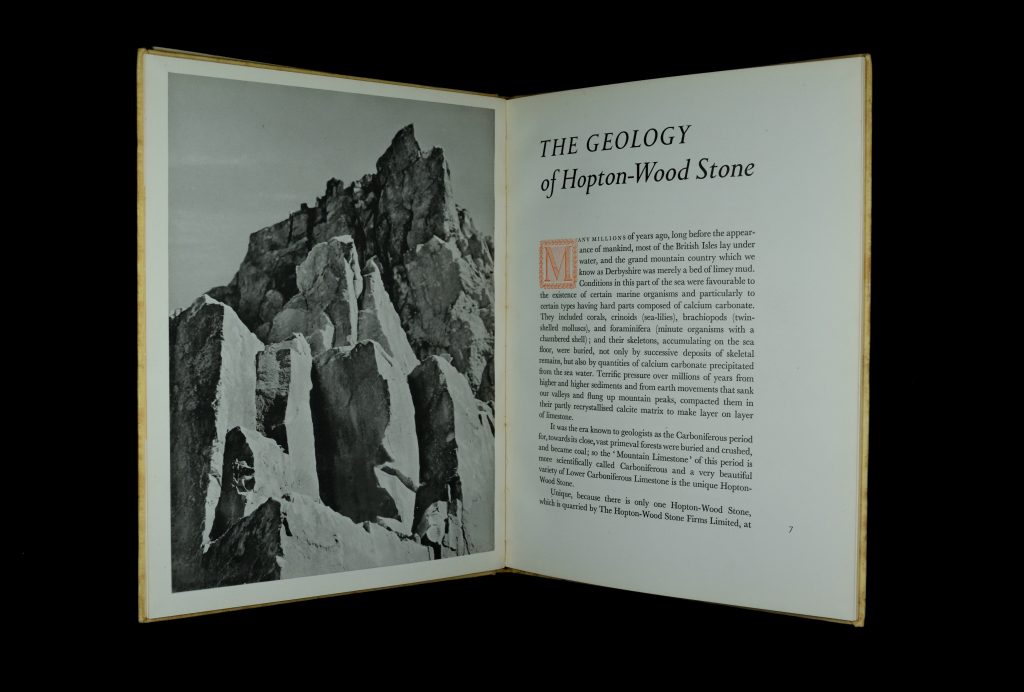

[Hopton-Wood Stone Firms Ltd.], Hopton-Wood Stone: a book for the architect and craftsman (London, 1947).

Collegium Reginae Oxoniense, Liber Vitae Reginensium: qui pro patria mortem obierunt MCMXIV-MCMXIX, (Edinburgh, 1922).

The Queen’s College Dedication of the War Memorial by Rt. Rev. Dr. H. H. Williams, Lord Bishop of Carlisle (Oxford, 1921)

Count Paul Esterházy (1883–1915)

Erich Joachim Peucer (1889–1917)

Carl Heinrich Hertz (1893–1918)

Gustav Adolf Jacobi (1885–1917)

[Hopton-Wood Stone Firms Ltd.], Hopton-Wood Stone: a book for the architect and craftsman (London, 1947).

Collegium Reginae Oxoniense, Liber Vitae Reginensium: qui pro patria mortem obierunt MCMXIV-MCMXIX, (Edinburgh, 1922).

The Queen's College Dedication of the War Memorial by Rt. Rev. Dr. H. H. Williams, Lord Bishop of Carlisle (Oxford, 1921)

Count Paul Esterházy (1883–1915)

Erich Joachim Peucer (1889–1917)

Carl Heinrich Hertz (1893–1918)

Gustav Adolf Jacobi (1885–1917)

Hopton-Wood Stone

[Hopton-Wood Stone Firms Ltd.], Hopton-Wood Stone: a book for the architect and craftsman (London, 1947).

Designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield, the architect of the Menin Gate at Ypres, the names on the College’s memorial are inscribed on a shelly, creamy-grey limestone from Derbyshire. Known as Hopton-Wood Stone, and formed over millions of years from the ‘skeletal remains’ of coral, crinoids (sea lilies), brachiopods, and foraminifera, it was marketed for its marble-like quality.

Following the end of the War, the Hopton-Wood Stone Firms Ltd. won a contract from the Imperial War Graves Commission for thousands of headstones, and the stone can be seen in cemeteries across the world. As a decorative stone, it was favoured by sculptors including Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth.

In October 2025, the additional names were inscribed by Oxfordshire Memorials in October 2025, using stencils as guides for the hand-chiselled letters.

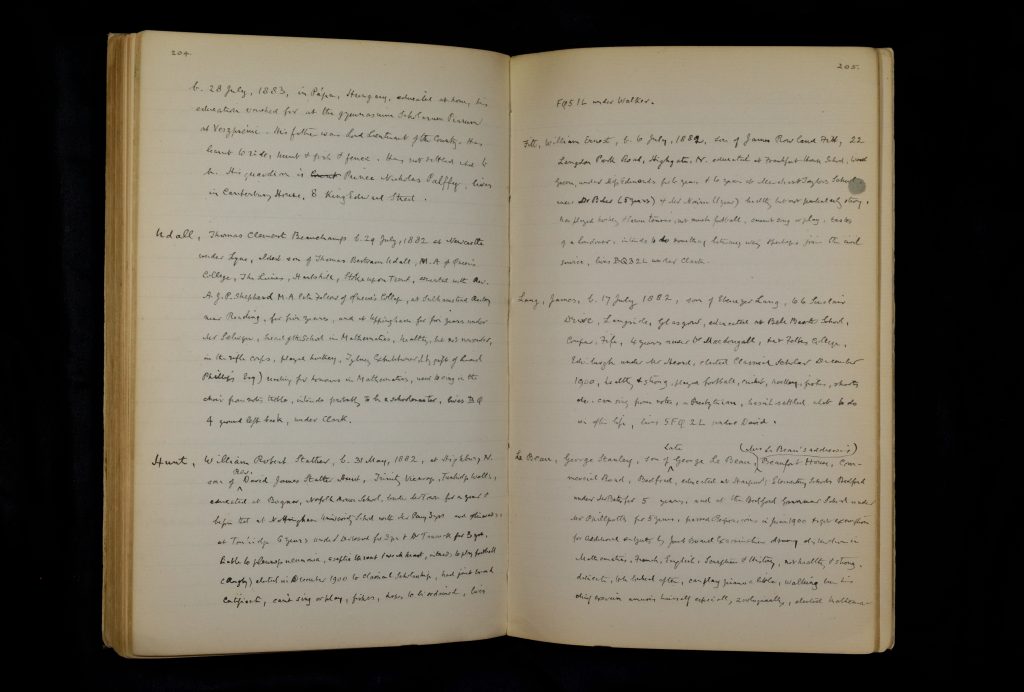

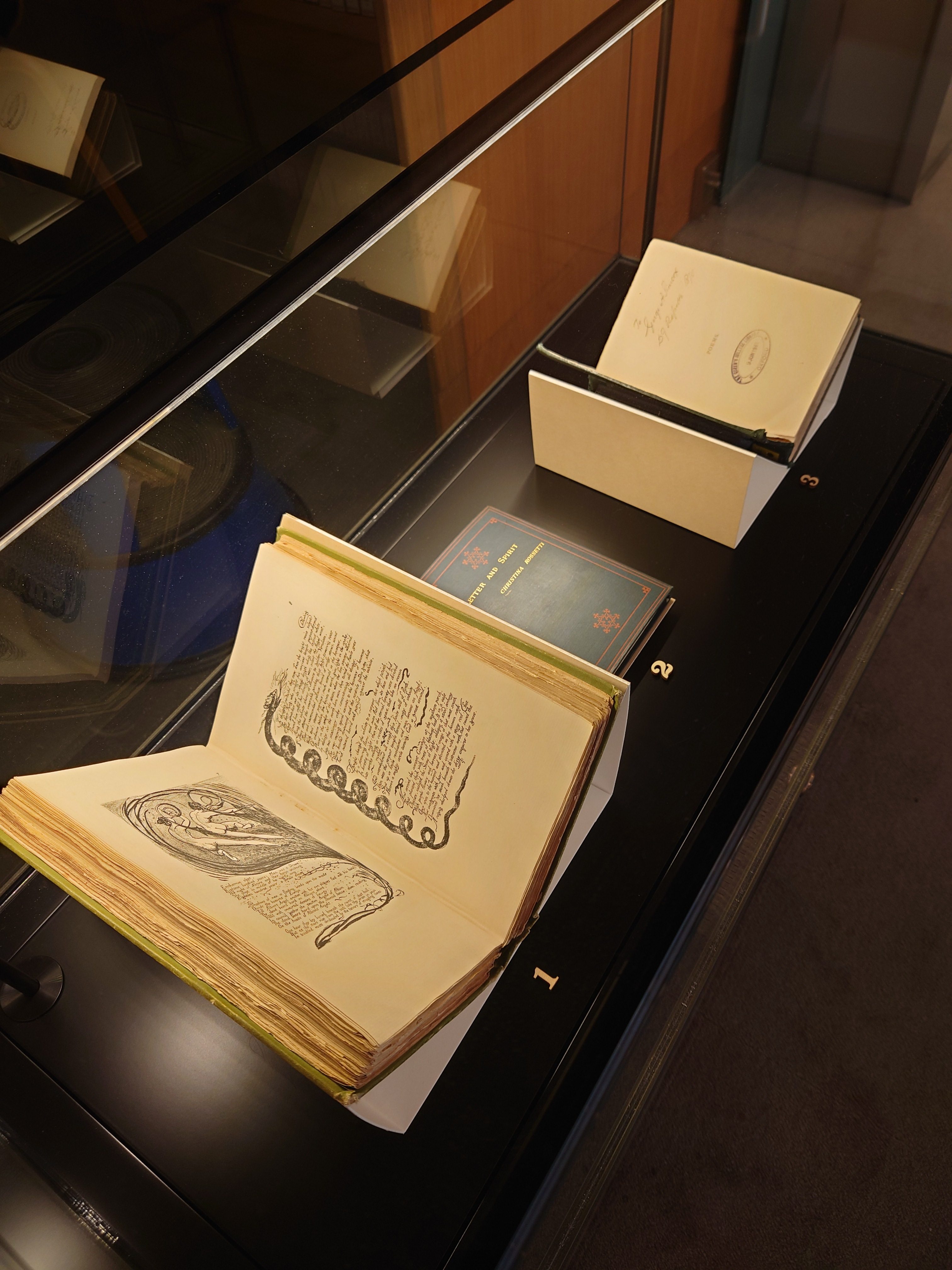

Liber Vitae Reginensium

Collegium Reginae Oxoniense, Liber Vitae Reginensium: qui pro patria mortem obierunt MCMXIV-MCMXIX (Edinburgh, 1922).

There was no set way of marking the sacrifice of current and former students, staff, academics, and choristers across the University. Impromptu lists and memorials were followed by more considered official commemorations.

At New College, all the college’s dead, including German alumni, were listed on the ‘pro patria’ list posted on the chapel door; a decision that led to a wide debate. Their names were absent from the 1921 Roll of Honour, but in 1930, a tablet with their names was placed alongside the Memorial. In 1941, a Canadian serviceman wrote to Life magazine describing the addition as ‘a quiet manifestation of what I have found to be a typical English characteristic’. German names are to be found in memorials in Rhodes House and, since the 1990s, in several other Oxford colleges.

Within the College, the Memorial Room and the Memorial Altar Cross in the Chapel provided two forms of commemoration. In 1921, the War Memorial outside the Library was unveiled, providing a focal point within the College. The biographies beyond the names were also commemorated in this ‘book of lives’ on display here.

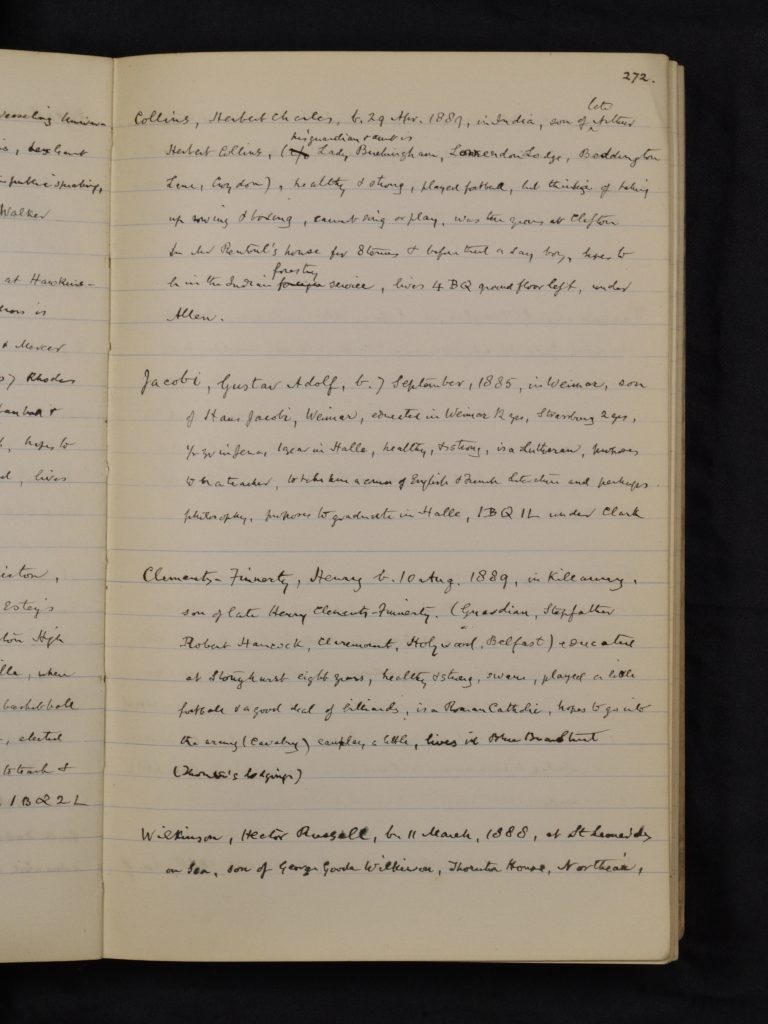

German and Austro-Hungarian Students

There were many links between Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Edwardian Oxford. In the academic year 1911–1912, forty-three Germans matriculated at Oxford, and over twenty Englishmen were studying in Heidelberg. Undergraduates could also join Anglo-German clubs and literary societies. The Rhodes Trust also provided two-year scholarships for German students. Many of these students came from aristocratic backgrounds, often with close links to British families, and treated a time in England as something of a social rite of passage.

The College hosted several of these students, particularly members of the august Hungarian Esterhazy family, including one future prime minister.

Count Paul Esterházy (1883–1915)

Count Pál Esterházy (anglicized as Paul) studied at Oxford during the academic year 1901–02, before reading law in Saxony. A popular figure, he was keen on riding, field sports, and fencing; he later regularly appeared in the society pages of the newspapers, notably the wedding of his friend Count Lázló Széchenyi to Gladys Vanderbilt in New York. Although the gossip columns suggested he would marry Gladys’ cousin, Dorothy Whitney, he instead returned to Pápa in Hungary, where he married Countess Ilona Andrássy.

When war broke out, he enlisted in a hussar regiment. Although serving as a commanding officer behind the line, he found ways to participate in a number of actions and was the first to leap into the Russian trenches in an attack in the mountains near Duratic. He later transferred to a field battalion, believing that the place of a Hungarian lord was fighting with his people. On 26 June 1915, while advancing in Dziewietniki, Galicia, he was shot and killed by Russian rifle fire as he attempted to observe the enemy positions through his binoculars. His tomb is in the church at Ganna. A service of commemoration was held on the centenary of his death.

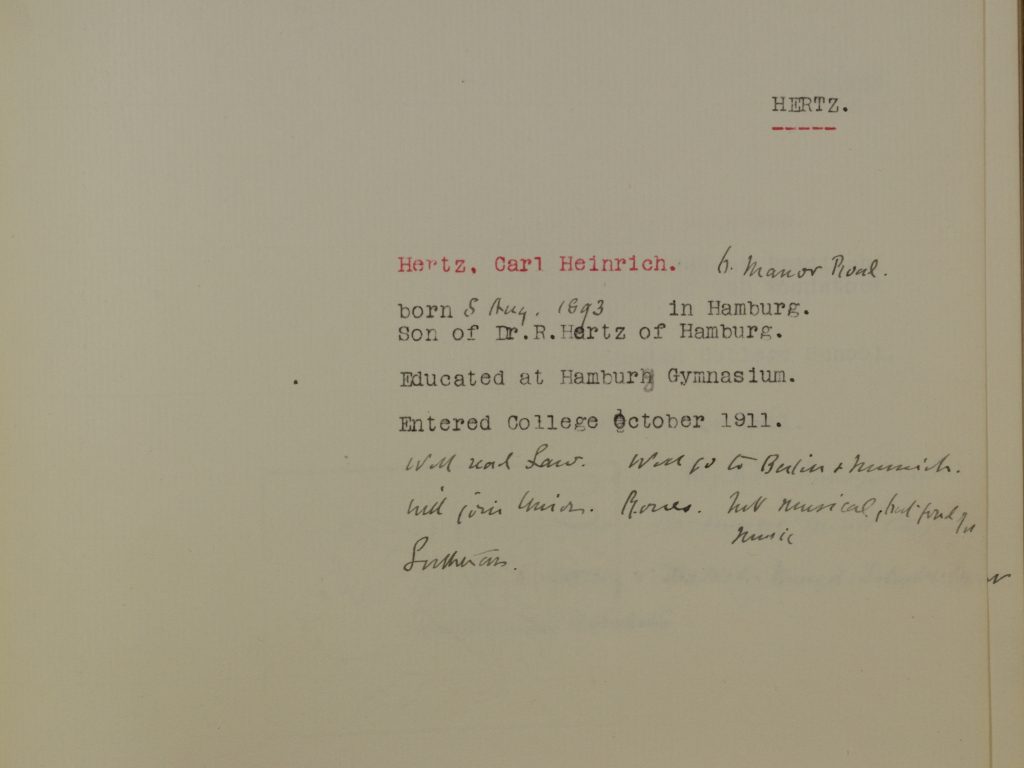

Carl Heinrich Hertz (1893–1918)

The nephew of the physicist, Heinrich Hertz, Carl was born in Hamburg in 1893 and entered the College in 1911 to read law. The Entrance Book noted that he rowed, would join the (Oxford) Union, and although not musical, appreciated music. During the War he flew in the German air arm and died in an air crash, probably after being shot down by the Canadian ace, Capt. A. W. Carter of 210 Squadron on 9 May 1918. Following his death, his family published a memorial volume, and commissioned a sculpture by Georg Kolbe depicting a ‘Falling Aviator’ with Icarus’s wings.

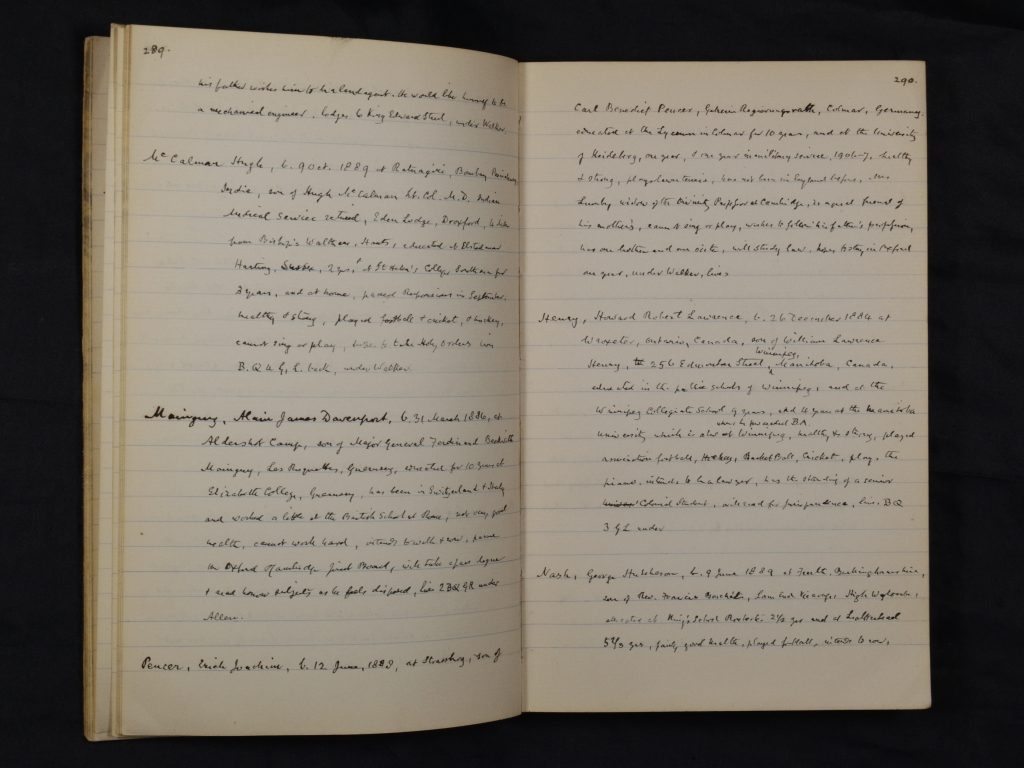

Erich Joachim Peucer (1889–1917)

Peucer was born in Strasburg, then part of Germany, and was a member of the Colmar family of Peucer, who traced their descent from the protestant reformer Philip Melanchthon. He studied at Heidelberg university and had spent a year in military service before matriculating at Oxford to study law. He followed his father into the civil service before volunteering in 1914. After serving in the foot artillery in Russia and France, he joined the German air force and died on service in Italy in 1917.

Gustav Adolf Jacobi (1885–1917)

Born in Weimar, Jacobi came to the College as a Rhodes Scholar in 1907 to read English Literature. During his time at Oxford, he completed a doctoral dissertation on the female characters in the plays of the Jacobean dramatists Beaumont and Fletcher, awarded by the University of Halle-Wittenberg in 1909. After further study and teaching, he joined the German army in 1914, and was killed in 1917. Jacobi is also commemorated in the Rhodes House war memorial.

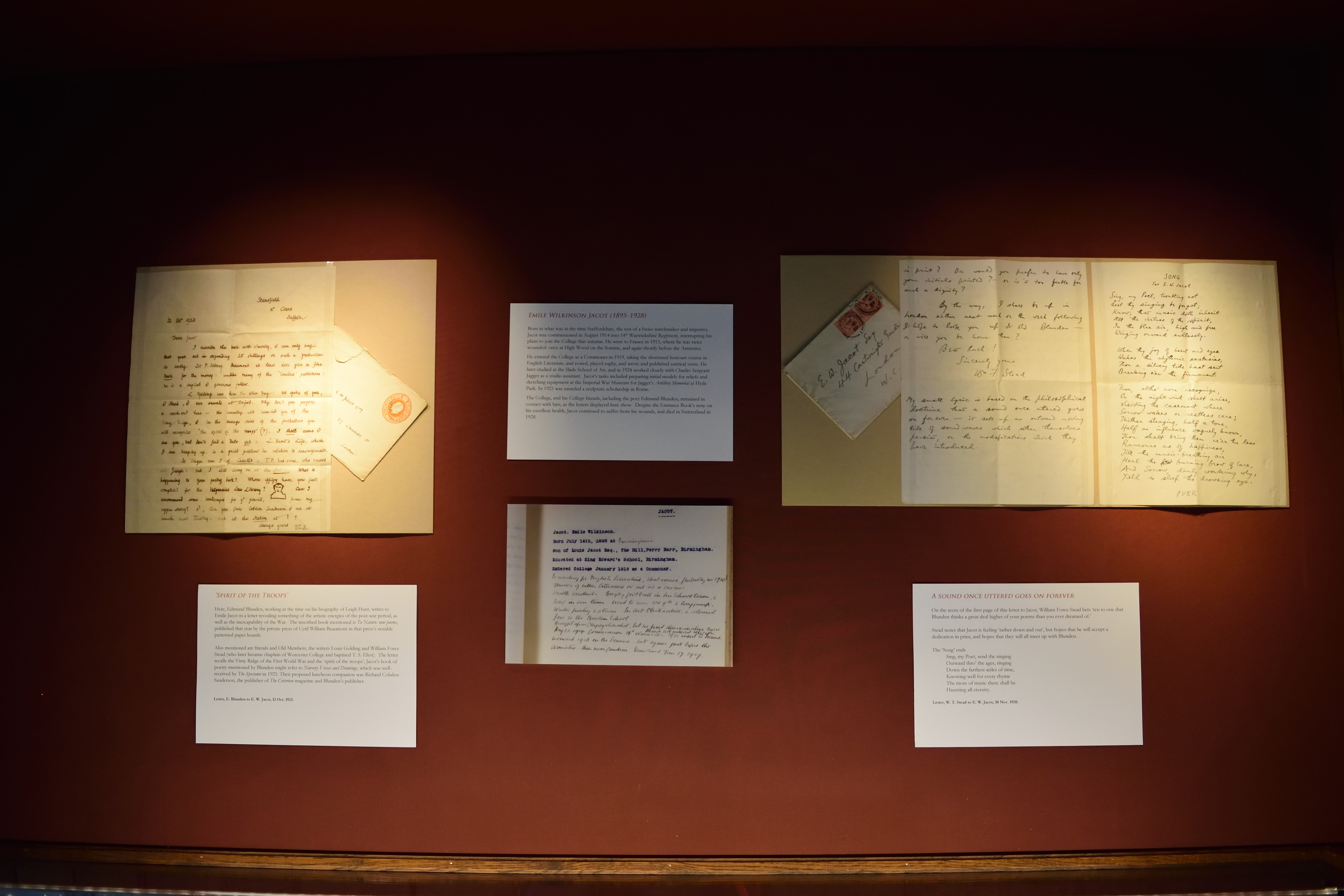

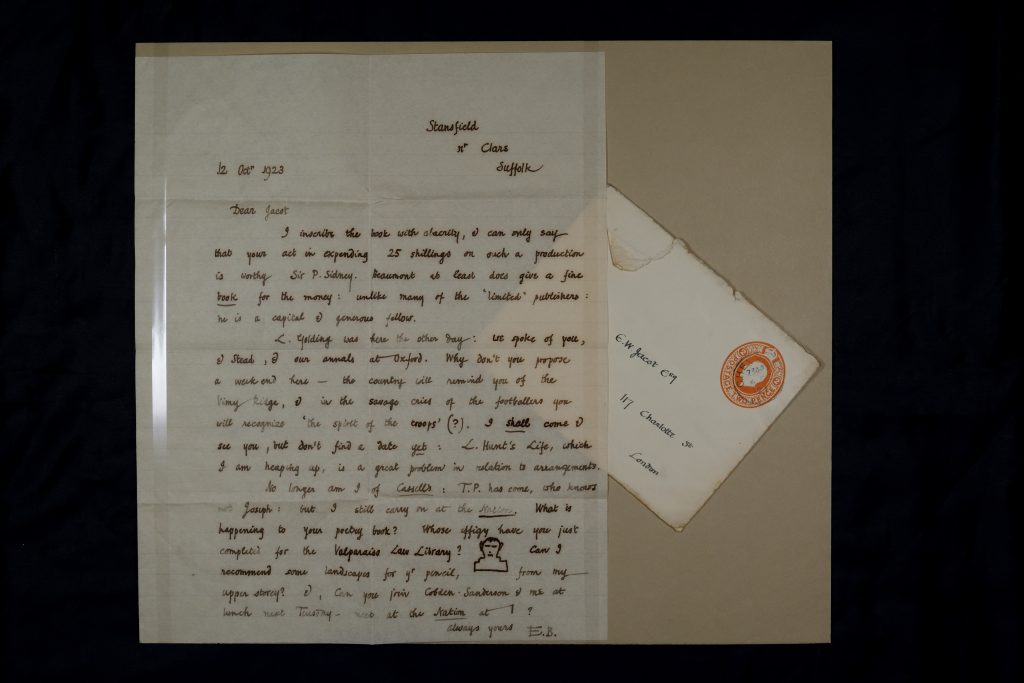

Letter, E. Blunden to E. W. Jacot, 12 Oct. 1923.

Emile Wilkinson Jacot (1895–1928)

Letter, W. T. Stead to E. W. Jacot, 30 Nov. 1920.

Letter, E. Blunden to E. W. Jacot, 12 Oct. 1923.

Emile Wilkinson Jacot (1895–1928)

Letter, W. T. Stead to E. W. Jacot, 30 Nov. 1920.

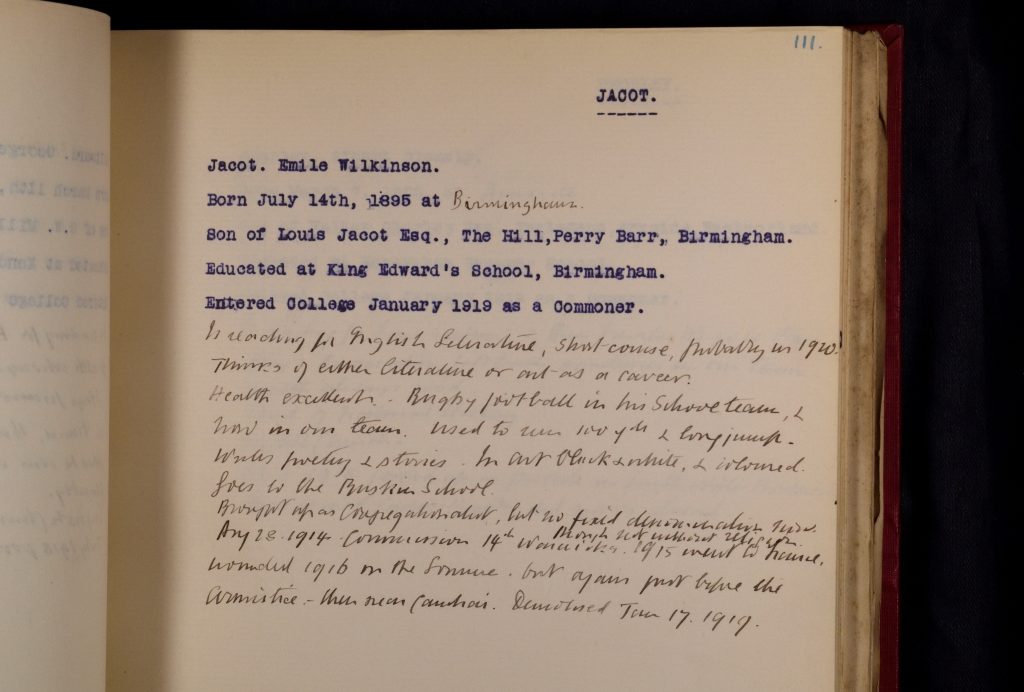

Emile Wilkinson Jacot (1895–1928)

Born in what was at the time Staffordshire, the son of a Swiss watchmaker and importer, Jacot was commissioned in August 1914 into 14th Warwickshire Regiment, interrupting his plans to join the College that autumn. He went to France in 1915, where he was twice wounded: once at High Wood on the Somme, and again shortly before the Armistice.

He entered the College as a Commoner in 1919, taking the shortened honours course in English Literature, and rowed, played rugby, and wrote and published satirical verse. He later studied at the Slade School of Art, and in 1924 worked closely with Charles Sergeant Jagger as a studio assistant. Jacot’s tasks included preparing initial models for reliefs and sketching equipment at the Imperial War Museum for Jagger’s Artillery Memorial at Hyde Park. In 1925 was awarded a sculpture scholarship in Rome.

The College, and his College friends, including the poet Edmund Blunden, remained in contact with him, as the letters displayed here show. Despite the Entrance Book’s note on his excellent health, Jacot continued to suffer from his wounds, and died in Switzerland in 1928.

‘Spirit of the Troops’

Letter, E. Blunden to E. W. Jacot, 12 Oct. 1923.

© Estate of Edmund Blunden. Used by permission.

Here, Edmund Blunden, working at the time on his biography of Leigh Hunt, writes to Emile Jacot in a letter revealing something of the artistic energies of the post-war period, as well as the inescapability of the War. The inscribed book mentioned is To Nature: new poems, published that year by the private press of Cyril William Beaumont in that press’s notable patterned paper boards.

Also mentioned are friends and Old Members, the writers Louis Golding and William Force Stead (who later became chaplain of Worcester College and baptised T. S. Eliot). The letter recalls the Vimy Ridge of the First World War and the ‘spirit of the troops’; Jacot’s book of poetry mentioned by Blunden might refer to Nursery Verses and Drawings, which was well-received by The Spectator in 1925. Their proposed luncheon companion was Richard Cobden-Sanderson, the publisher of The Criterion magazine and Blunden’s publisher.

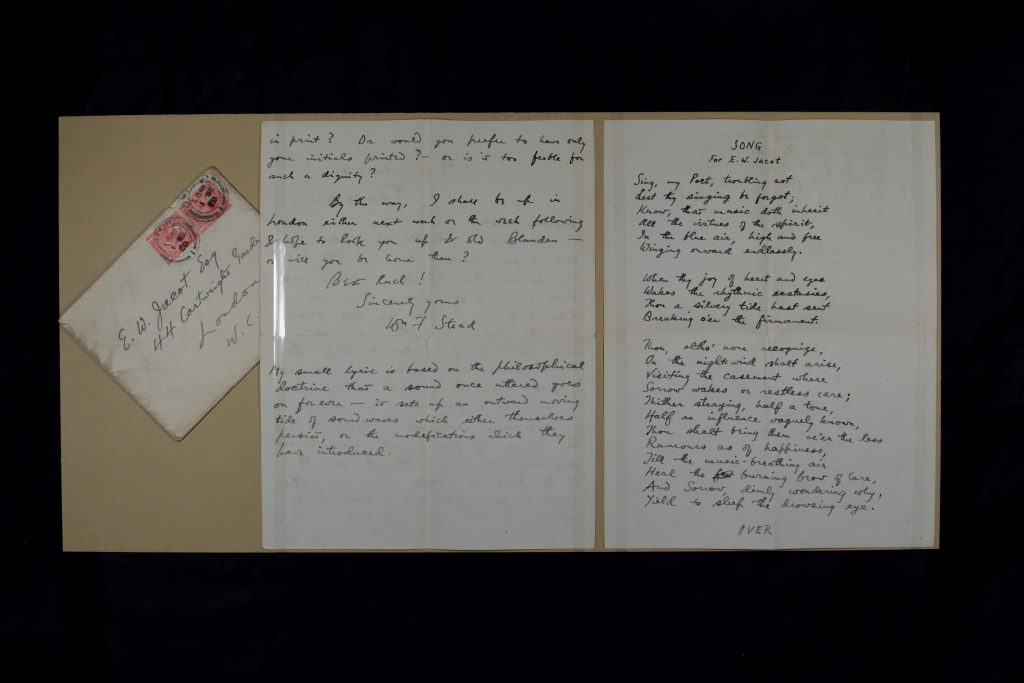

A sound once uttered goes on forever

Letter, W. T. Stead to E. W. Jacot, 30 Nov. 1920.

On the recto of the first page of this letter to Jacot, William Force Stead bets ‘ten to one that Blunden thinks a great deal higher of your poems than you ever dreamed of.’

Stead notes that Jacot is feeling ‘rather down and out’, but hopes that he will accept a dedication in print, and hopes that they will all meet up with Blunden.

The ‘Song’ ends

Sing, my Poet, send the singing

Outward thro’ the ages, ringing

Down the farthest aisles of time,

Knowing well for every rhyme

The more of music there shall be

Haunting all eternity.

Curated by Dr. Matthew Shaw, College Librarian.

Every effort has been made to identify and contact the copyright holders of the material featured on this page. We welcome any information that might help us correctly attribute this work. Please direct any enquiries to library@queens.ox.ac.uk.

Explore more of our exhibitions

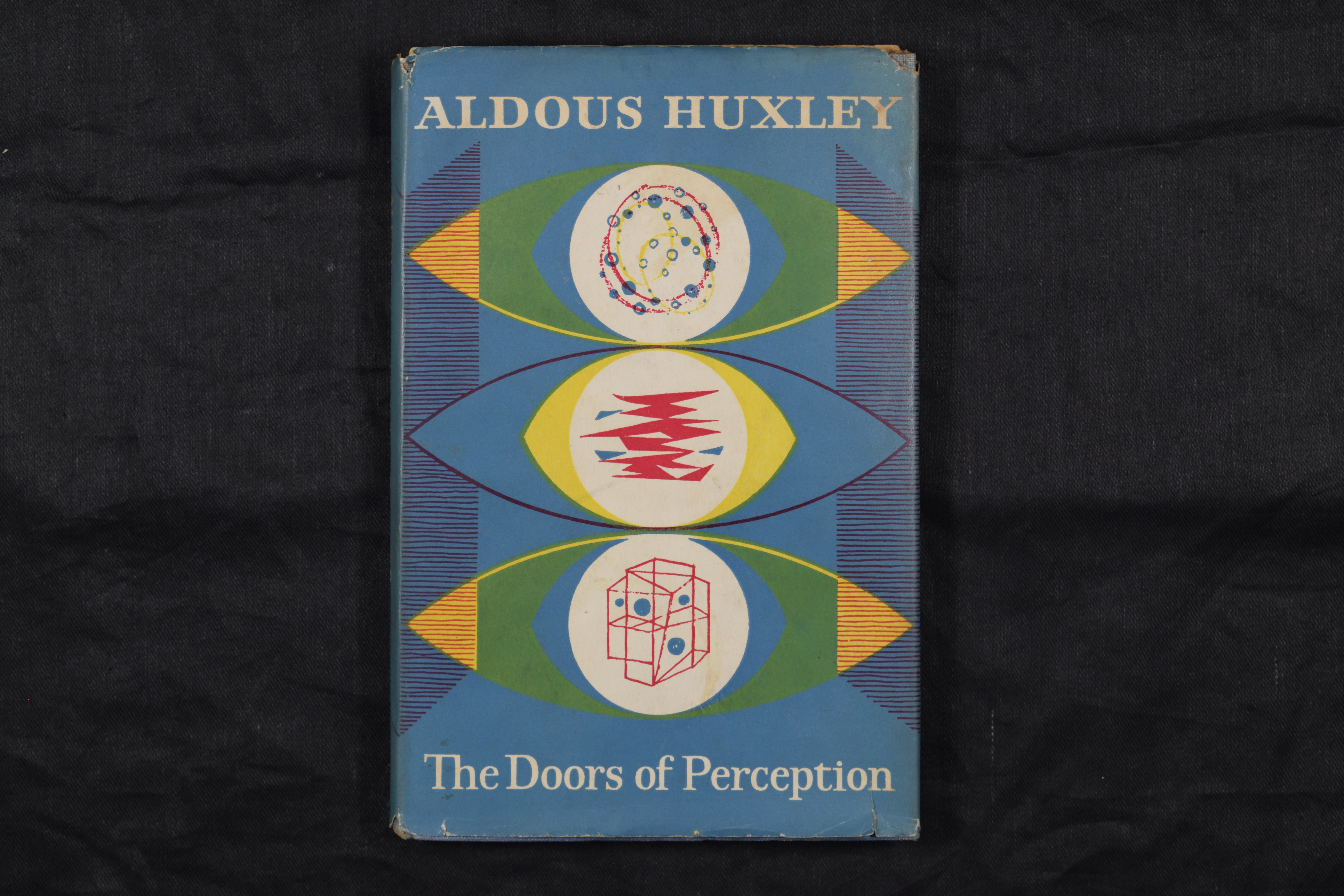

Perception: an exhibition

‘From the author’

Joseph Williamson and the establishment of the transatlantic slave trade