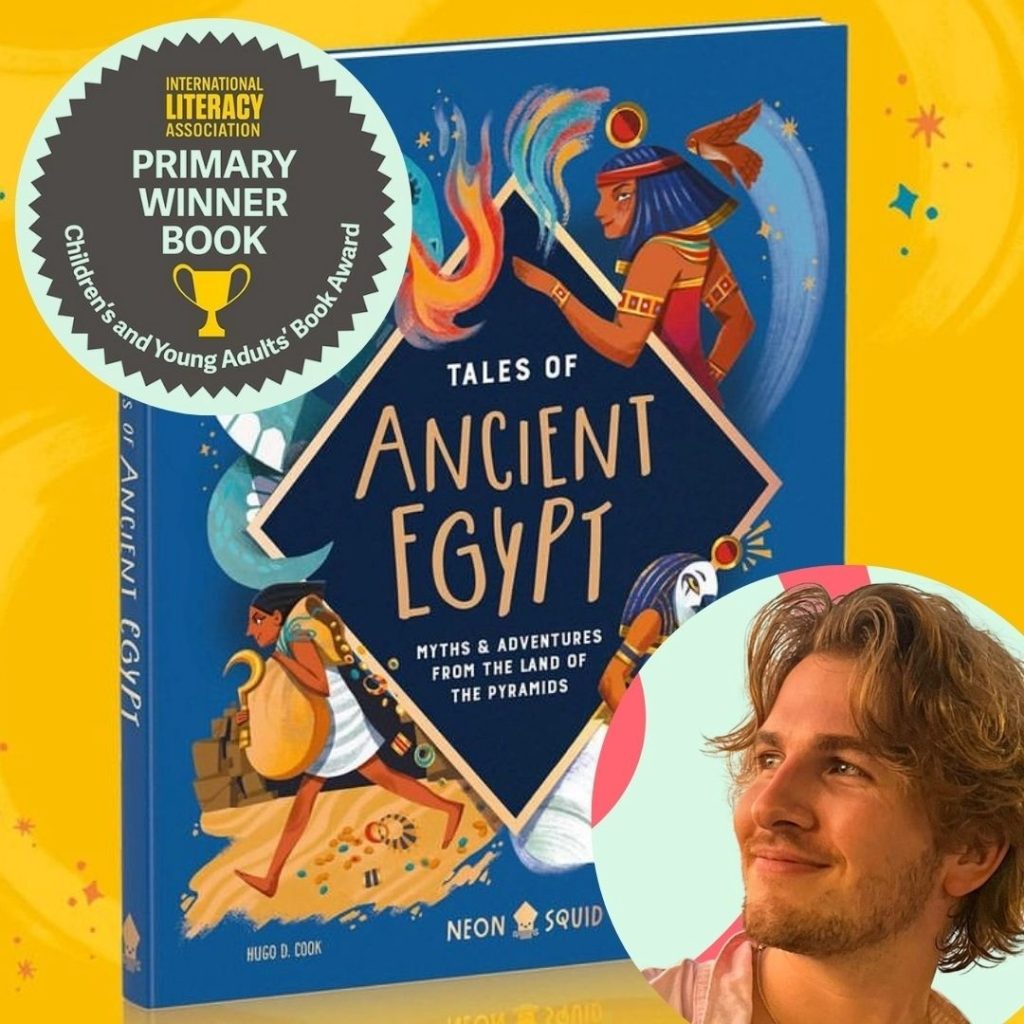

The College congratulates Hugo Cook (Egyptology, 2017) who has won an International Literacy Association Book Award in the ‘Non-Fiction for Intermediate Age’ category with his first book, Tales of Ancient Egypt.

The book, beautifully illustrated by Sona Avedikian, is a collection of Egyptian stories, many of which had never been translated from hieroglyphs for the general public before: from a true ‘Ocean’s 11th Century BC’ story of pyramid-robbers, to the fictional siege tale that might have inspired Homer’s Trojan Horse, to the only pre-Hollywood myth of walking talking mummies. We asked Hugo to tell us more about the book and how his work at Queen’s helped to shape the stories it tells.

What do you hope children learn from the book?

With anything educational, I realise I’ll never have enough time to teach anyone everything I want them to know. That’s the case with lecturing adults, and it’s certainly the case with writing a children’s book. So, my utmost goal, especially with a younger audience, is not so much to convey knowledge as it is to ignite wonder. Wonder’s great. If I can make a child go “wow,” then hopefully they’ll head off towards a lifetime of curiosity and reading and they’ll learn things I never could have taught them. That was something I really wanted with this book. Good children’s books on Egyptology, like the famed golden one with the red gem which my generation all adored, gave me that gift of wonder and now I want to pass it on. So, while the stories are interspersed with ‘context pages’ that give factual information about topics ranging from astronomy to gastronomy, my main hope for the book was that it would inspire children to go and excitedly explore the wonders of the past, whether those wonders were made with ink or stone.

Wonder’s great. If I can make a child go “wow,” then hopefully they’ll head off towards a lifetime of curiosity and reading and they’ll learn things I never could have taught them.

Your book blends scholarship and storytelling. How did you decide which stories made the cut?

Thankfully, the ancients themselves helped with the decision process: a lot of the best stories are often either too philosophical or too salacious, which made them easy to cut out. I wanted to prioritise stories most people hadn’t heard before. It always astounds me how many tales there are, and how few are widely known. More writing survives from ancient Egypt than survives from all of medieval Europe put together – there is so much that is known, but so little that is widely disseminated. That’s odd for a topic that attracts such universal fascination and I wanted to remedy that. I wanted to show the scale and depth of ancient Egypt, the beauty, the fact that there’s always some brilliant new thing to discover. So, I focused on stories that hadn’t been translated or published for kids before and chose ones that I thought would be gripping: stories filled with adventure, or magic, or emotion, or humour. I tried to fit as many in as the word limit would allow, and when that came closing in, I mentioned others in brief summaries. I even added some classics, like Cleopatra’s story, but relied on the original ancient texts rather than the whisper-game effect that’s distorted those narratives today.

What’s your favourite story in the book and why?

When I have kids, I’ll find it easier to publicly pick a favourite child than to answer this. My mind instantly jumps to a historical fiction written in ancient Egypt, which is basically the Trojan horse story: only the wooden horse is a mass of giant horse-feed sacks, the walled city is walled Jaffa, and the story was written centuries before Homer was born. It has a fabulous fable-like feel to it, in the heat of a dramatic wartime narrative full of deadly backstabbing and drunken brawling. But as I’m speaking, another story butts it out the way to take the lead: yes, my favourite is probably a set of magical stories about Egypt’s first Egyptologist. He was Ramses the Great’s son, one of 200 children there, which meant an heir and many spares to do odd things like become an Egyptologist. Unlike the rest of us though, his tomb-delving and conservation work led him to posthumously become this sort of all-powerful Merlin figure in literature, who has vast powers and who epitomises knowledge without wisdom. The rest of us only get the knowledge-without-wisdom part. His wizarding adventure stories are wonderful, and well worth a read. That said, another contender just spoke up from the back of my mind: as someone who grew up with Brendan Frasier and Rachel Weisz in The Mummy, that dark part of my brain is suggesting the Coptic text that includes Egypt’s only pre-Hollywood tale of a walking talking mummy. Who couldn’t love that.

Where did you find the stories?

They come from a range of sources in a range of languages: I used texts written in hieroglyphic Egyptian, hieratic Egyptian, Demotic, Coptic, Latin, Greek, and Old Persian for this book. Some were written out as dramatic tales intended to be read, others came from stranger places. For instance, one story was from an 11th-century BC courthouse: it was the testimony of a real-life stone mason on trial for robbing an even more ancient pyramid. We all imagine legal texts as being dull, but I realised this would make a great story: a first-person account of a heist, complete with assembling a gang of specialists, tackling corrupt police, setting fire to mummies to find the hidden gold within, and stealing the kind of treasure that we don’t find in pyramids anymore. It was just waiting to become a proper heist story. I pitched it to the publishers as Ocean’s 11th-Century BC. Nobody laughed at that though.

You include both historical stories and myths. What do you think we gain by reading them side by side?

I think it’s nice to remember these were real people. The mythology is certainly interesting, but it’s easy for that to be all children learn, and soon antiquity becomes Middle Earth or Narnia to them. I think it’s great to see historical tales and mythological stories side-by-side and realise they’re just as interesting as each other. It’s good to remember that real people, the ones who built the world we stand on, can be just as fascinating as fire-breathing gods. We’re just as mad after all. I think it helps that oh-so-important sense of wonder.

You’re known to many as ‘Hugo the Egyptologist’ on TikTok. How has your audience on social media shaped the way you approach storytelling in print?

Other than summoning a nervous sweat any time one of my new students at the British Museum says, “Hang on, you’re that guy from TikTok” and I have to assure the others I’m not on there doing little dances (yet), I think it’s been great for confirming what I’ve always known: history, all history, is engaging. Let me give some context here. Early in my career, I was asked to help with a documentary series and throw some ideas at the network. It had to be something about six Roman characters, so I chose six obscure but brilliant figures I thought would make people say, “Wow I never knew that, how interesting.” The network told me they didn’t want that: they wanted six world-famous figures like Julius Caesar, so their audience would say, “Wow I already knew that, I feel good about myself.” That was an enlightening and gloomy window into the current state of knowledge dissemination. I disagreed with that approach, and what social media showed me was that I wasn’t just being an idealist in doing so, a silly academic who’s never had to crunch the numbers or conduct a market survey. Those obscure topics I talked about online garnered millions of views per video, because people are curious and hungry and wonderful. I think that’s what history is, it’s an appreciation of humanity despite all our chaos, and so if you practice history then you have to trust that humans, even now, are capable of more than that television network believed.

I think that’s what history is, it’s an appreciation of humanity despite all our chaos.

You first translated some of the stories in the Peet Library at Queen’s. What was it like to follow in the footsteps of famous Egyptologists in the College?

It was brilliant to have access to such amazing resources, but also daunting. I nervously babbled a lot around my lecturers, as I worried I came across as an ‘Egypt fanboy’ more than a talented scholar compared to them. It was only during my master’s degree that I gained self-assurance and confidence about all this, probably because of the increased focus on independent research. Those qualities oddly made me a much better researcher, and now the nervous babbling has become joyful babbling.

What did you enjoy most about your time at Queen’s?

The wonderful friends I made, and watching them squabble for library desk space through the window of my comfortable and effectively private Egyptology library.

How did you first get interested in ancient Egypt?

I can vividly remember building a model shadoof, a sort of Egyptian water crane, back in Year Three of primary school. I remember moving it about, twisting it back and forth to pick up the blue marbles I used as the ‘water.’ Even then I was genuinely enthralled that people thousands upon thousands of years ago could build something so clever yet so simple. Across the UK, every year, you see a swarm of Year Three children descending on Egyptology books, newly and rightly hungry for anything they can learn about the topic. I was among them. But then the calendar pages turn, and the children move on to Romans or dinosaurs or whatever it is they fall in love with next. Not me though. My obsession had grown roots, and it wasn’t coming loose, despite the later effort of relatives who wanted me to use my knack for speaking to become a lawyer. I read more and more, occasionally having books confiscated after learning all the naughty words from mythology books far beyond my age range. The source of my interest changed, or perhaps revealed itself: the excitement of learning about people with a vastly different culture, but a very familiar humanity. The more I read, the more I loved it. As the expression goes, the larger the island of knowledge, the longer the shoreline of wonder. Those relatives and I can all now agree it was worth it.

What does winning mean to you, especially for a subject as ancient (and sometimes misunderstood) as Egypt?

As someone who wants to do a lot of writing, it’s very exciting. We’ve all been taught the lessons about the importance of self-belief and such, but a little external validation now and then does hit the spot. That said, in all things to do with this book, I applaud not myself but the Egyptians, past and present. It was their wit and genius that conjured this civilisation, these stories. I’m just, as I once feared, the ‘Egypt fanboy’ who tries to show that wit and genius to new audiences. That’s a good thing to be though. Even if I’m raising up the name of ancient tomb robbers who were impaled on big wooden spikes for all to see, I feel constantly aware they’re the superstars, and I’m just grateful to be on the PR team. So, a big thank you to the people of the Nile: not just for this book prize, but for a life of meaningful pursuit and amazed appreciation. Onto the next book!