In November 1922, as Egypt became an independent nation, the archaeological world was turned upside down with the discovery of one of the most culturally significant ancient Egyptian royal burials. The discovery of the largely intact tomb of Tutankhamun would propel its excavator, Howard Carter, and photographer Harry Burton to international fame.

In celebration of 100 years since the discovery of the tomb of this young king, the Bodleian Libraries are pleased to announce a special exhibition covering this momentous event in Egypt’s history with fresh eyes. Tutankhamun: Excavating the Archive will run from 13 April 2022 to early February 2023 at the Weston Library.

There is so much more to the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun than ‘golden treasures’: the excavator’s archive lets us see beyond the colonialist popular stereotypes, and it documents the humanity of the modern and ancient people who worked on the tomb. The excavation was not achieved by a solitary heroic English archaeologist but by the modern Egyptian team-members, who have so often been overlooked and written out of the story. We hope the exhibition will contextualize, interrogate and criticize the famous discovery that it commemorates.

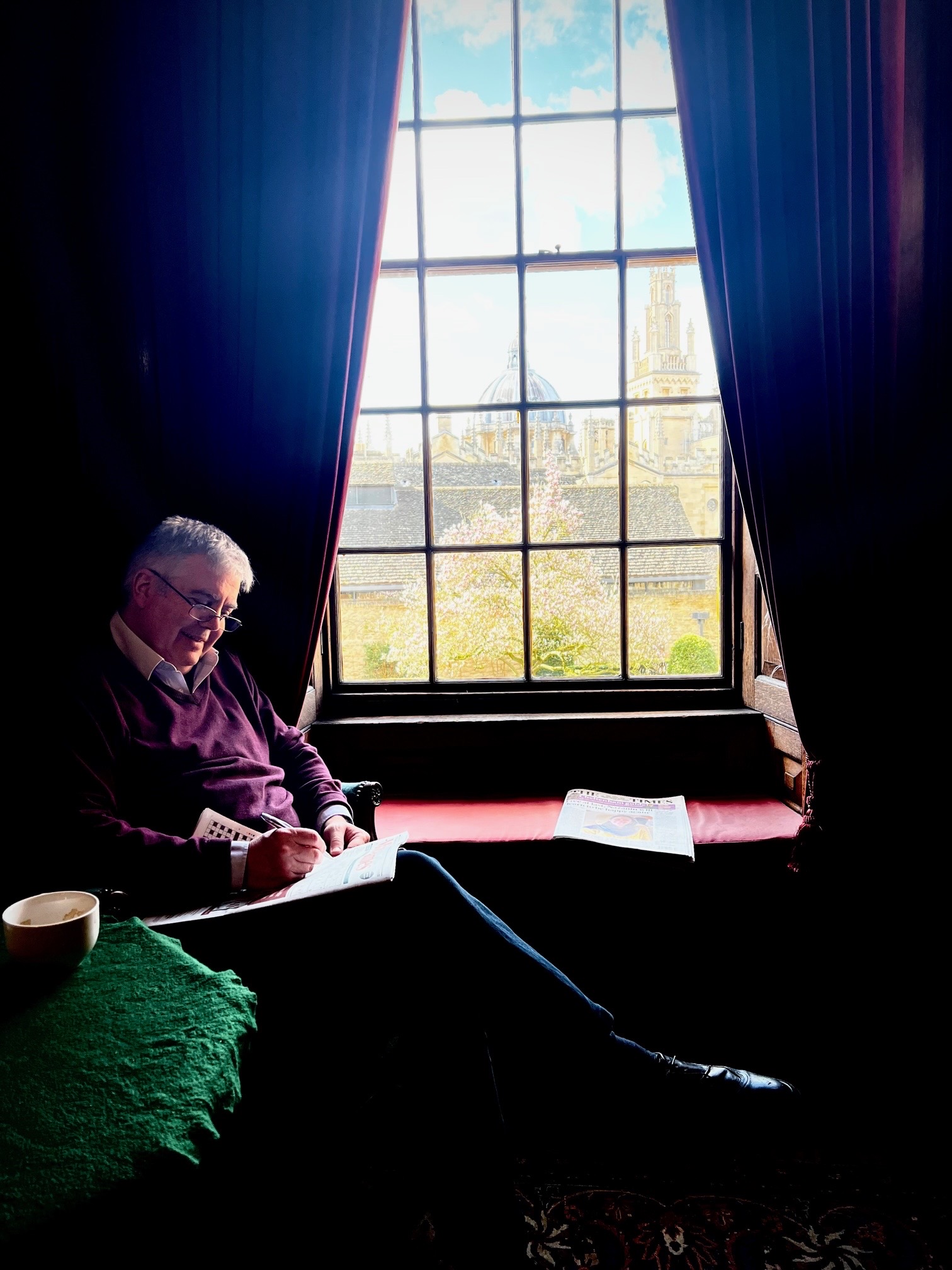

Co-Curator, Professor of Egyptology and Fellow of Queen’s Richard Bruce Parkinson

Flythrough the tomb of Tutankhamun

We asked Professor Parkinson to tell us more about the exhibition.

The records of the ten-year excavation by Howard Carter and Lord Carnarvon following their discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun are stored in the archive of the Griffith Institute, Oxford’s centre of Egyptology. How did you go about selecting which pieces to display for this new exhibition?

The staff of the Griffith Institute chose the items for the exhibition and for the accompanying book, drawing on their long experience of curating the archive. So it is quite a personal view and one that that only they could provide; I’ve curated the project simply because I’ve had experience in museum displays and publications. We’ve included many of the most iconic images, but also some less familiar ones, and ones that show familiar objects in unexpected ways, still garlanded as when they were deposited in the tomb in 1320 BCE. We also want to let people see the full range of the different types of records and the sheer quality of the images that Harry Burton, the excavation’s photographer, took.

What is your favourite piece from the archive on display at the exhibition?

It’s a drawing of the tomb and its contents done by my northern art-teacher father—he did it in the 1970s in order to teach me measured perspective when I was keen on Egypt. It was based on materials from the archive and became part of the archive in the 1980s. He died in 1995. As Christina Riggs has perceptively said, exhibitions about Tutankhamun should be about histories of ‘death and loss’, and this drawing is very much about that for me. Dad would have been very surprised and pleased to see it side by side with Carter’s drawings (but to be honest, I think his draughtsmanship is much better than Carter’s).

How is this exhibition different from other exhibitions about Tutankhamun?

This exhibition is about the excavator’s archive, and not the ‘treasures’. We really want to show that there is more than gold to Tutankhamun – to reveal ‘a chronicle no longer gold’ in Tennessee William’s phrase. The items record at first hand the modern history of the discovery, with all the personal and political conflicts, but they also show us the intensely human processes of the ancient burial, as with one photograph of the little wreath of olive leaves that someone placed on the coffin during the funeral. The golden king was the same age as our undergraduates when he died.

What is the most enjoyable aspect of curating a new exhibition?

With this one, it’s been working so closely with the wonderful exhibitions team at the Bodleian, and also with my co-curator Dr Daniela Rosenow of the Griffith Institute. I used to work at the British Museum, so it’s been very nostalgic for me to be back in such a collaborative ethos. Seeing how design shapes the message of an exhibition is always a joy.

What are some of the challenges of putting together an exhibition that covers such a famous discovery?

A famous discovery can become a bandwagon, with a lot of competing claims on the narrative; everyone wants to profit from it. For me, the biggest challenge has been tackling the real curse of Tutankhamun’s tomb—the popular stereotype of a Downton Abbey-style ‘golden age’ of colonialist archaeology. We’re trying to present the discovery in its historical context and complexity, to interrogate it and not to celebrate it. As part of this, we want show visitors the role that women played in the excavation, and above all the role of the Egyptian team-members, who were often written out of many official accounts. So the gallery will showcase a set of photos of an Egyptian boy wearing an ancient pendant from the tomb. Although the excavators took these images simply to illustrate the pendant’s method of suspension, and didn’t even record the boy’s name, they are immensely evocative of the links between the worlds of the living and the dead. And for me, that’s what Egyptology is about.

Photos: Ian Wallman, 2022