Book history has been one of the most exciting subfields in the humanities over the last couple of decades, something confirmed by a recent symposium, Built with Books: Shaping the Shelves of the Early Modern Library held at UCL in September 2025. Part of the Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded project Shaping Scholarship: Early Donations to the Bodleian Library, the two-day symposium brought together a broad range of graduate students, academics, librarians, and curators to explore the current state of research into the creation, use, and impact of early modern libraries.

The College was represented by Prof Tamara Atkin, Fellow in English, who gave the keynote lecture on the first day, and by the College Librarian, Matt Shaw, who presented as part of a panel.

Double Books

The symposium revealed how much remains to be discovered in the archives, particularly when sources are re-read with fresh eyes and new methodologies. Prof Atkin’s keynote revisited the infamous disposal of the Bodleian Library’s original 1623 First Folio of Shakspeare’s Comedies, Tragedies & Histories. As the story is usually told, a copy of this now hugely valuable and famous volume arrived in Oxford in 1623 and, in early 1624 was bound by William Wildgoose in a typical Oxford style. Chained at the Arts End of the Library for consultation, it remained the only Shakespearean holding listed in the 1635 appendix to the Bodleian’s 1620 printed catalogue. Around 1640, however, it was reshelved and later it vanished altogether. The 1674 printed catalogue records instead the Third Folio of 1664, suggesting that when this expanded Restoration edition arrived the earlier volume was deaccessioned – likely sold off with other superfluous books to the Oxford bookseller Richard Davis. This has long been interpreted as evidence of a policy to discard earlier editions when newer ones became available. But is that really what happened?

But is that really what happened?

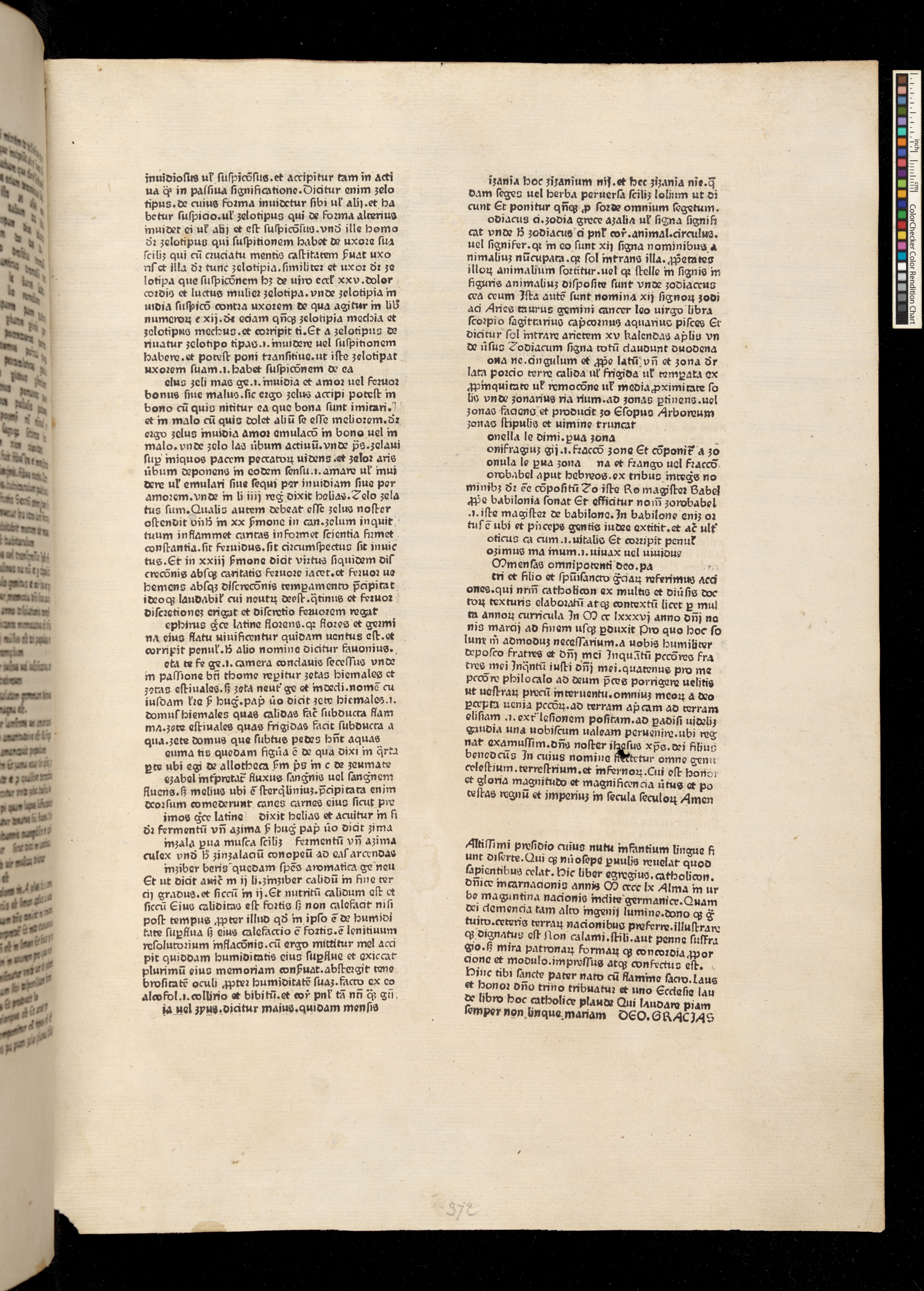

Drawing on the Bodleian’s Daybook (Library Records e.9) – a record kept by the Library’s First Keeper, Thomas James – Prof Atkin challenged the idea of a systematic policy of deaccessioning older editions. The Daybook lists “double books”, or duplicates, in remarkable detail, showing that early Bodleian librarians were cautious and conservative custodians, who carefully assessed a range of bibliographical data when deciding which books to retain or discard. The age of an edition was rarely a consideration, but format, size, binding, and volume composition were all taken into account. Even so, many titles marked for removal remained on the shelves for decades, suggesting that as long as space allowed, duplicates were tolerated.

The same may have been true of the First Folio. Its disappearance likely stemmed not from policy but from practical pressures, crowded shelves, and the arrival of the Third Folio, whose seven extra plays made it the more comprehensive edition. By returning to the evidence of day-to-day record keeping, Prof Atkin revealed a library more pragmatic and flexible than policy-driven, its decisions shaped as much by circumstance and opportunity as by principle. Her lecture demonstrated how earlier collecting practices and understandings can be illuminated by close readings of archival evidence.

The Upper Library

Earlier in the day, I contributed to a session exploring methodological framings. As College Librarian, I am interested in the early history of the Upper Library, and how its physical construction was linked to the donations or bequests of major collections by Provost Thomas Barlow, Sir Joseph Williamson (Fellow), and Provost Timothy Halton. Methodologically, I highlighted how anecdote and rumour can become accepted as fact in institutions such as the College, particularly given the paucity of the historical record. At the same time, there are clues not just in the Archive but in the books (and their subjects), the shelves, and the building itself, all pointing to what was intended by the construction of the new Library at that point in the College’s history.

It was clearly a statement of confidence, at a time when the College could boast some of the largest student numbers in the University and had close connections to the restored royal court. Its architectural borrowings (from Cambridge and France) also spoke of a desire to project a modern, international image. Clues such as a note in the Bodleian’s manuscripts collection recording a visit to Cambridge by John Townsend, the Library’s builder (and likely “architect,” to use a modern term), shortly before construction began, suggest that the Wren Library at Trinity College may have been a direct inspiration. Even more intriguingly, although Halton is credited with bequeathing his library to the College, only a handful of books now bear his name. He was certainly keen for the Library—and the neo-Classical College—to be built, but a sale of his books at the University Church, recorded in a newspaper classified advert, suggests that his library was a source of funds rather than reading matter. The Library’s archives contain a series of notes by a relative of Provost Joseph Smith, pointing to where the story of Halton’s library goes awry through the misrecording of an earlier letter.

There was much more, of course, during the rest of the symposium. Interest in what the creation (and destruction) of institutional and personal libraries reveals about the lives, assumptions, and passions of the past touches on a host of disciplines, from Materials Science and Sociology to the more expected History and Literature. Many papers also demonstrated the increasing use of digital technology, including artificial intelligence to assess entire collections, and sophisticated databases that make available details of the contents, owners, and provenance of these treasure houses of the past. Together, these approaches are transforming how we understand the history of books – not just as texts, but as objects that record networks of use, exchange, and meaning. The symposium showed how the study of libraries continues to illuminate the evolving understanding of and relationship between knowledge, culture, and community.

The study of libraries continues to illuminate the evolving understanding of and relationship between knowledge, culture, and community.

![A book page from 1613 with the title 'Double books to be exchanged according to [the] pleasure of...'](https://www.queens.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Double-Books-cropped.png)