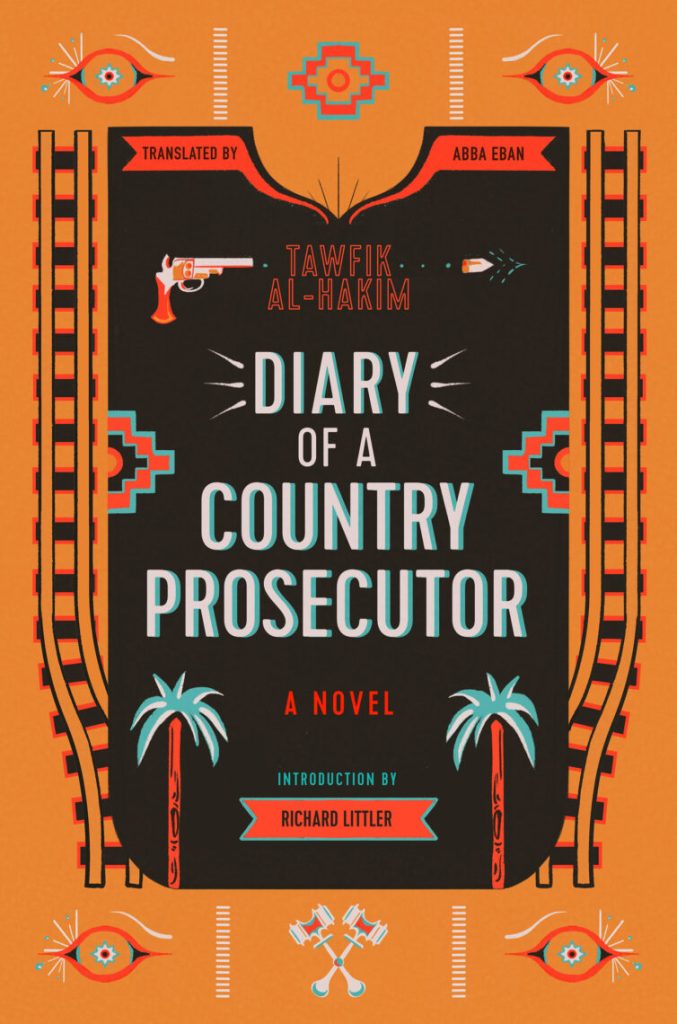

Saqi Books kindly offered review copies of Tawfik al-Hakim’s classic Diary of a Country Prosecutor, first published in 1937 and newly rereleased, to participants of our International Book Club for Schools. We are committed to exposing young people to the diversity of world literature, and affording them the space to express their critical responses. Opinions expressed in these reviews are of the student author alone. Tracey Owusu Frimpong (Year 13) wrote the following review for The Translation Exchange:

The text itself is an unsolved criminal case, where the indisputable delinquent is the 1920s Egyptian judicial system, and whose victim is the uneducated rural fellahin. These peasants have no care except God’s, which is not transmitted justly through the hands of earthly powers. Such a case remains unsolved as there is no punishment for a corrupt system which does not honestly seek justice. Rather, it seeks to quickly honour the impracticalities of legal administration through selfish means, having boxes ticked off whilst countless men and woman die or pay for sins which they have not committed. A poor old man is punished with a month of hard labour for feeding his family with the untaxed wheat that he himself grew. Amid anguish, a wounded man ends up ‘expired’ during the process of unnecessary detailing of his attire. Even a poisoned woman who is basking in her own ‘vomit and excrement’ would not be left alone until at least a name came out of the lips of her suffering body. Moral aptitude is trumped by legalistic rules which the common countryside Egyptian would not understand, making those in the higher courts richer and more influential. Through dry-wit humour, the novel’s protagonist – the countryside ‘prosecutor’- criticises this miscarriage of justice through a series of personal diary entries. This is the essence of the matter in Tawfiq al-Hakim’s partially autobiographical Diary of a Country Prosecutor.

I often found myself thinking that al-Hakim’s deadpan comical style perfectly reflects the known quote ‘if you don’t laugh you will cry’. There is surely a seriousness appreciated by the prosecutor in his work whilst recognising the barbarisms of legal expectations. I chuckled when the prosecutor stated that ‘God willing’ he would be more careful in writing out a murder case in at least twenty pages, instead of the mere ten which actually allowed him to catch the murderer! Furthermore, the constant use of prophetic Mawwal song spouted by the seemingly lowliest and insignificant vagrant ‘Shaikh Asfur’, presents an ongoing irony: the ostracised part of Egyptian society will still be ignored even if they have a valuable voice in a matter. This notion becomes cataclysmic throughout the text’s most major murder of Kamar al-Dawla Alwan, with the young ‘beauty’ Rim being the clearest yet least regarded suspect of the officials.

As a translation of Modern Arabic literature, I believe that Abba Eban has provided an accessible interpretation of the original text in his English edition. As an amateur in this particular literature, I found myself meeting the author in his home country, sensitive to the cultural and religious milieu of rural Egypt. The ease in reading and understanding the text with the glossary of Arabic terms such as ‘ma’mur’ and ‘galabieh’ supported by P.H. Newby’s insightful foreword, solidifies Diary of a Country Prosecutor as a text to be recommended.