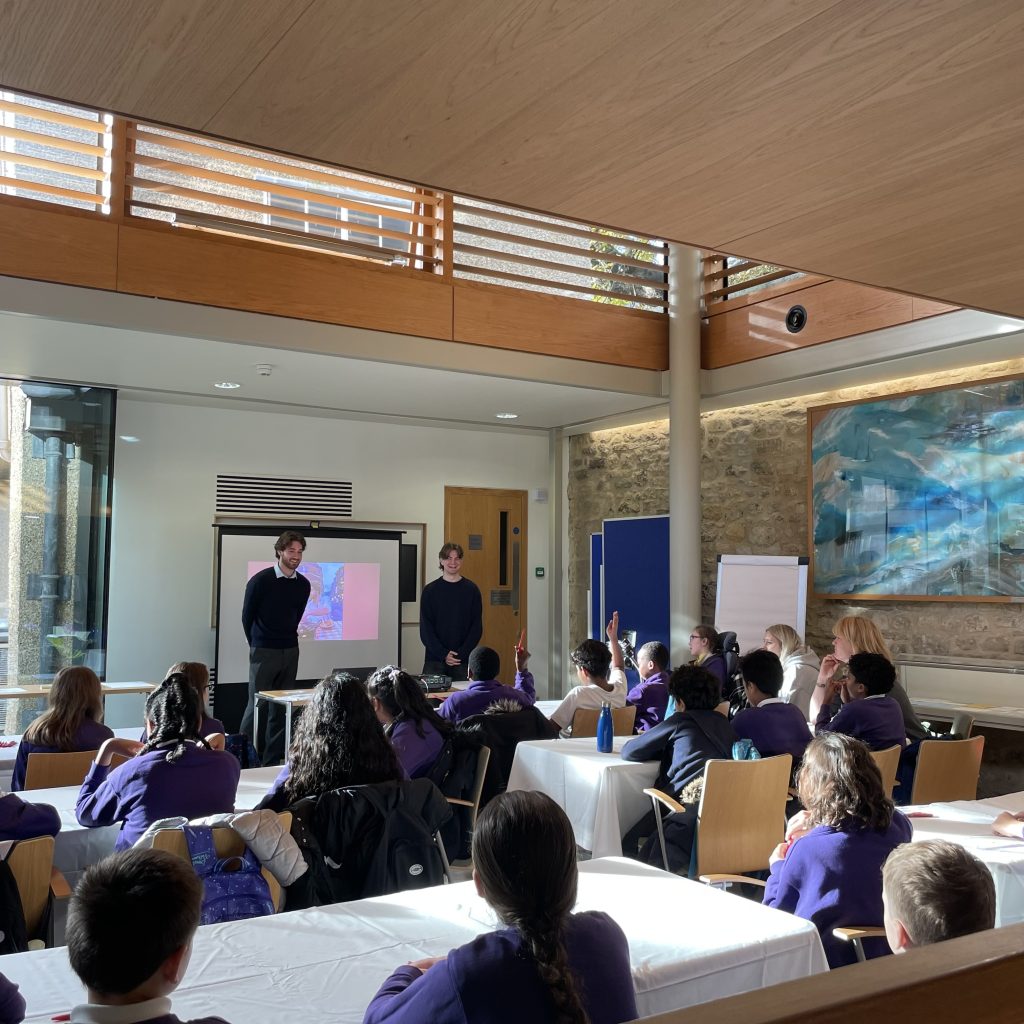

In Trinity Term 2025, QTE ran a Creative Translation Ambassadors training day with 2nd-year languages students who are about to take up teaching placements on their year abroad. This training was delivered in cooperation with the Modern Languages Faculty, and was the first time undergraduates were trained to teach translation from authentic English-language texts into their target languages, so they can use this method while teaching abroad.

We asked QTE Policy Coordinator Jack Franco and Anthea Bell Prize Coordinator Cat Parry to tell us more about this new approach.

What inspired the idea to train undergraduates to teach translation while abroad?

Anyone who has studied Modern Languages at university has contemplated teaching English on their year abroad, or actually gone on to do so. It can be unpredictable and overwhelming, with limited support from schools or other bodies to show you the ropes: how to teach, how to teach your own language, how to manage a classroom. When I was a teaching assistant in Marseille for a semester during my year abroad, all those fears came together when my teacher resigned mid-term, and I was left to teach entire lessons…

We thought that our Creative Translation Ambassadors programme, which has run so successfully in British schools, could be the key to unlocking a rewarding teaching experience for university linguists abroad, as well as for their pupils. Language learning in schools abroad often suffers from the same problems as in the UK: uninteresting, ineffective content. It is also an idea that can expand QTE’s reach and visibility by putting the Creative Translation method to the test: if translation is about learning a language in order to and by understanding the other, then others should have the chance to learn creatively about anglophone cultures and communities. The idea was to train a cohort of ambassadors in the more literal sense of the term!

Language learning in schools abroad often suffers from the same problems as in the UK: uninteresting, ineffective content.

What kind of impact do you hope this training will have on the students’ teaching experiences abroad?

We hope that the training will empower Modern Languages students to feel more confident bringing authentic texts and literature into their teaching whilst on their years abroad. We know from our work with schools and teachers across the UK that Creative Translation is not only really rewarding and motivating for students, but also for teachers. It’s a way for the undergraduate ambassadors to integrate literature and culture that interests them into their teaching in a way that is engaging, accessible, and inclusive for all students, no matter their level and knowledge of English. If teachers are teaching something that they find exciting and inspiring and interesting, then that enthusiasm translates to the students!

Creative Translation is not only really rewarding and motivating for students, but also for teachers.

How do you see this benefitting the schools or institutions our students will work with overseas?

Creative Translation isn’t just about teaching a language; it’s about valuing languages and the act of translation, as well as recognising all the skills and attributes that come along with being a linguist, and ensuring that a wide range of voices and perspectives are represented within the curriculum. We hope that this training will help our ambassadors to design and deliver teaching that raises the profile of languages and language-learning in their host schools and institutions, and which celebrates the rich variety of languages already spoken in that community. The dream outcome is that by seeing the Modern Languages students in action, along with the response from the students, other languages teachers will be inspired to explore Creative Translation methods and approaches in their own classrooms.

What kinds of texts or themes are being used in the training, and why?

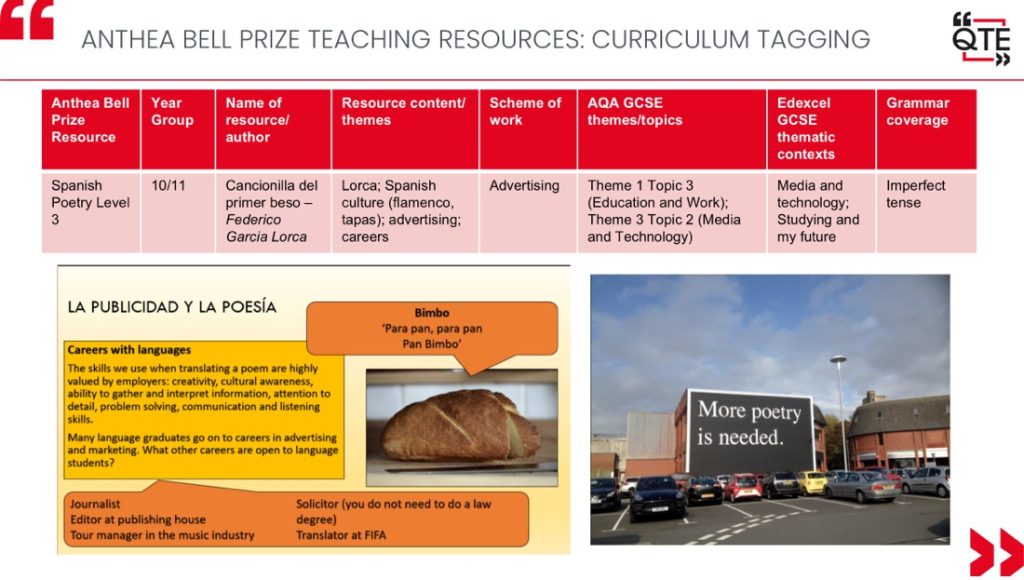

Creative Translation works well with a whole range of texts: poetry, fiction, non-fiction, lyrics, picture books. Since it is a scaffolded activity, virtually any text can be made appropriate to the learner’s stage by providing a more or less complete glossary, shifting the emphasis on creative appropriation of language. In the training, we focused on poetry, and how to plan several lessons or class projects around a single text. First, we delivered a standard Creative Translation workshop from Spanish to English, using the poem ‘No sé por qué piensas tú’ (‘I don’t know why you think that’) by the Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén, so our ambassadors could get a feel for the method; how to guide students from awkward, literal translations, to personal, fluid literary translations. We then inverted the process: what is it like to teach an English text into your target language? We worked through the resource I had developed in Marseille for a creative translation of William Blake’s ‘The Tyger’, and looked at the final translation my students had made.

How did students respond to the training day?

It was a pleasure to have 20 modern linguists from across the University attend the training, and their engagement throughout the afternoon was impressive and encouraging. It felt like a moment in which students realised the potential to take the knowledge they are acquiring at Oxford out of the tutorial and into the world, giving more pupils the taste of studying languages and the cultures they contain.

Students left the training feeling more prepared for their upcoming placements; one student who had not yet committed to teaching abroad even remarked:

I absolutely loved this session – I was undecided on whether to study or teach on my year abroad, but this might have persuaded me.

Lily, studying German and Linguistics, said to us at the end:

It all suddenly feels much easier [because] the session provided useful and tangible ideas ready to use next year.

What skills do you think they’re taking with them into their year abroad?

Creative Translation is a holistic method: it’s about saying we can’t separate how effectively students learn from their affective relationship to the subject. Through creative translation, ambassadors learn how to motivate pupils to learn difficult language exactly because they want to understand what is being said in a poem or a dialogue, how to create an inclusive environment that values and makes use of pupils’ diverse backgrounds and languages. If these are the effects on the pupils, they in turn have the same effects on student teachers by connecting their studies to lived experiences in multilingual classrooms. These are pedagogical and human skills, of course, but can also be seen as part of their academic, research-based development: fieldwork in the study of languages!

QTE’s Director, Dr Charlotte Ryland, often talks about creating a ‘community of linguists’ that cuts across history and geography in pupils’ encounters with great texts. It’s also about putting young university linguists in dialogue with even younger ones, showing what languages can do for how you think and live. Sending Creative Translation Ambassadors abroad is another step in building this intercultural, generous, critical community of linguists.

What does this initiative say about the evolving role of undergraduates as ambassadors—not just learners, but teachers and cultural interpreters?

This year’s training programme for Year Abroad students was a pilot of training we now hope will become a mainstay of year abroad orientation sessions, and that can be replicated by other universities or bodies such as the British Council. It is a natural progression for the Creative Translation Ambassadors programme after six years of success in British schools, and shows a different, complementary side to what it means to be an ambassador for languages and translation: going abroad, using your skills as a linguist to introduce others to anglophone culture. It as close to a lived experience of creative translation, of being creatively translated, as you can get. Students are leaving Oxford for a year, but taking a part of Oxford languages with them as teachers, being that bridge between cultures and generations that translators are.

Students are leaving Oxford for a year, but taking a part of Oxford languages with them as teachers, being that bridge between cultures and generations that translators are.

Why is Queen’s and the Faculty’s support for this kind of project meaningful in the context of Modern Languages today?

A large part of QTE’s work is to normalise the rather radical idea that languages should be motivating, fun, and challenging just because the prize of mutual understanding is worth the hard graft of linguistic and cultural translation. The current settlement for languages in the UK, and much of Europe, does its best to discourage pupils and demotivate teachers by subjecting pupils to dry content that does not make use of teachers’ expertise as graduate linguists. In this context, Queen’s support is invaluable. Anyone who has studied MML at Queen’s is aware of the strong tradition of languages study here: there are few better advocates for languages than the Fellows, students, researchers and alumni of this College.

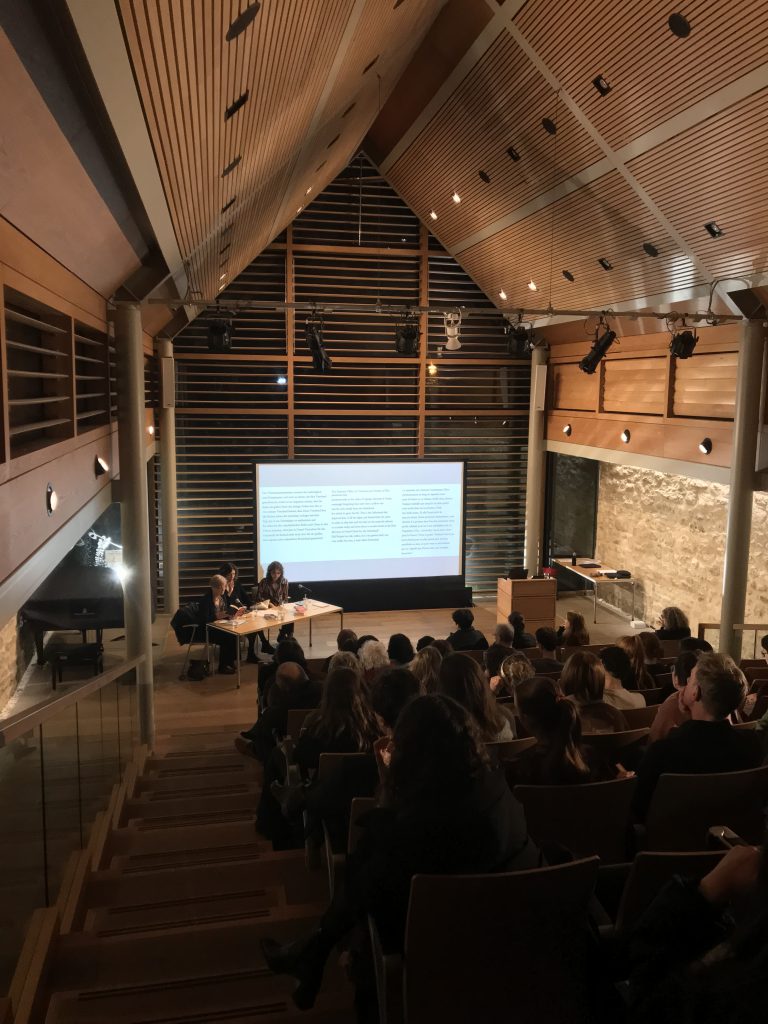

Equally, the possibility to strengthen our on-the-ground work with the Faculty directly with undergraduates across the University has been invaluable. Professor Simon Kemp, Admissions Director at the Faculty and Fellow in French at Somerville, opened the session on behalf of the Faculty, and even shared his own year abroad experience as a young French student. Embedding these creative opportunities in the experience of the undergraduate linguist is essential, and benefiting from the help of the Year Abroad and Education Offices at the Faculty has been crucial to this first step.

Lucy Venables, the Faculty Education Manager, had the following to say after the session:

We were thrilled that QTE were able to offer our second-year students this fantastic training opportunity. It was a brilliant session, where students were introduced to the exciting world of creative translation and provided with the tools to design their own lessons for use during their teaching placements. We look forward to hearing how they utilised the skills they gained from the training, and hope that we will be able to offer this to future cohorts. Thank you to Jack and Cat for running such a fantastic session!