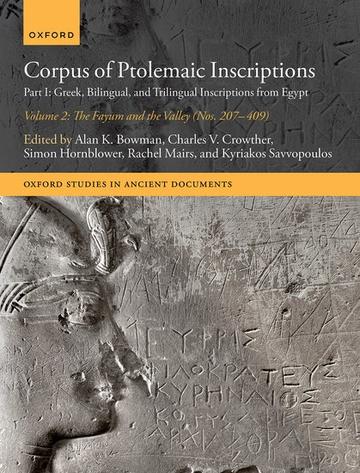

Oxford University Press has published a major new collection of Ptolemaic-period Egyptian inscriptions, for which our Fellow in Ancient History, Dr Charles Crowther, has served as principal editor alongside Queen’s Honorary Fellow Professor Alan Bowman.

The new volume brings together a remarkable 300-year sweep of inscriptional records, offering freshly revised texts of key documents in both Greek and Egyptian. By setting these sources side by side, the editors open a clearer window onto the intricate interplay between Greek and indigenous Egyptian religious institutions, revealing a complex cultural landscape.

A distinctive feature of the Corpus is that multilingual inscriptions are presented in single editions with Hieroglyphic, Demotic, and Greek texts together, rather than divided between separate language volumes in different sections of a library. As Alan Bowman observes, ‘It hardly needs pointing out that in order to see the Rosetta Stone one does not have to go to three different rooms in the British Museum.’

It hardly needs pointing out that in order to see the Rosetta Stone one does not have to go to three different rooms in the British Museum.

We asked them to tell us more about this work.

What aspect of the new volume do you feel most significantly advances our understanding of Ptolemaic Egypt?

Prof Bowman: It is precisely this multilingual approach that most significantly advances our understanding of the culture and role of inscriptions brought by the Greeks to Egypt.

Was there a particular inscription or group of texts that proved surprising or revealing?

Dr Crowther: A group of inscriptions from villages in the Fayum oasis records successful appeals to the Ptolemies by priests and local sponsors to grant asylum rights for their temples, to provide sanctuary for refugees and protection against extortion by local officials. The language of the documents is surprisingly modern with complaints about slanders and shakedowns by tax collectors.

If you could highlight one insight from this volume that you’d want students or non-specialists to know, what would it be?

Prof Bowman: How specific aspects of the society were expressed in different ways and different languages by adjacent groups with increasing interactions over time.

Is there an inscription in this collection that you feel captures the human story of the period particularly well?

Dr Crowther: Although most of the documents in the Corpus are quite formal in character, a few preserve personal insights. In the Ptolemaic period the healing cults of two deified legendary figures, Amenhotep and Imhotep, attracted visitors to the mortuary temple of the 18th-Dynasty Queen Hatshepsut (1473–1458) at Deir el-Bahari on the western side of the Nile. Polyaratos, one of these visitors, has left a dramatic testimony of his cure from a chronic lymphatic condition in February 260 BC. The surviving text, written in black ink on a smoothed limestone shard, is a draft full of crossings-out and insertions and vividly reflects the process of composition. Polyaratos writes that after failing elsewhere to find a cure he visited Deir el-Bahari to seek help from Amenothes and found it through incubation, by sleeping in the sanctuary and receiving a communication from the god in a dream which itself proved therapeutic.

Prof Bowman: The human stories are captured particularly well by the metrical epitaphs/epigrams in Greek which commemorated the deceased.

What was the most challenging or rewarding part of bringing this volume together, especially given the huge range of works?

Dr Crowther: Inscriptions in Egypt have not been easily accessible in recent years; our researcher Kyriakos Savvopoulos required a military escort for visits to sites in Upper Egypt during one fieldwork expedition. For many texts we have had to draw on archival copies, photographs, and paper casts in our own and other collections; the reopening of the Graeco-Roman Museum in Alexandria in October 2023 allowed us to check this work, and to our relief find that it stood up well.

A copy of the book can be found in the College’s Peet (Egyptology) Library.