Fellow in Physics Prof Robert Taylor retires at the end of this academic year after 35 years at Queen’s. We asked him to reflect on his time here and tell us how both Physics and the College have changed.

What first drew you to the field of Physics?

That’s an easy one: it was my father. My father was an electrician who worked for the Steel Company of Wales in Port Talbot. He used to look after the electrical side of the blast furnaces, eventually becoming the person who ran the power for the plant. He taught me a lot about electrical wiring and maths and that sparked an interest which I pursued at school. I had been torn between Chemistry and Physics until Swansea University ran an open day when I was in 6th form and their taster lectures made it really obvious to me that I didn’t want to do Chemistry or Maths. So, I applied to Oxford for Physics.

How did you find studying at Oxford and what brought you to Queen’s?

Oxford was an interesting one because I was from a small comprehensive in South Wales; there were two of us who were interested in going to an English university and one of our teachers said to us, ‘Why don’t you try for Oxford? You won’t lose anything.’ So, we both applied, and my friend Carol got into Girton for Biochemistry, and I got into Hertford to read Physics.

I received a studentship to stay on in Oxford for my DPhil and got to work on an excellent project on time-resolved spectroscopy of solids. It was a very new subject at the time, and we had brand new lasers. When I arrived at the lab, there was an optical table and one laser and then all the equipment arrived in my first year, which meant I learned how to use everything from scratch. We had two fantastic post-docs, who have ended up with stellar careers, and they taught me everything I needed to know, one being an expert in cryogenics, and the other an expert in lasers.

After my DPhil, I had a Junior Research Fellowship at St John’s so was doing some teaching for them and then I applied for, and was awarded, a Royal Society University Research Fellowship. This meant that I had my own independent research group for five years. While I was doing that, the Fellowship at Queen’s came up and I started here in 1990.

How has your view of the discipline evolved over the years?

Over my career, although I’ve always worked with lasers, I’ve researched three main topics. One was to work on what’s called “hot electrons”, which is basically now what’s inside the mobile phone. This became fully commercial by 1992, so I looked for something new and noticed that there was a new material called gallium nitride, used in the first blue LEDs. I had a friend who worked in the Materials Department in Oxford who was also interested in nitrides. She then moved to a big research group in Cambridge and we kept our collaboration going. For 15 years that proved to be a real goldmine for excellent research where we worked on optoelectronic devices, lasers, single photon sources, and cryptography.

The third thing I looked at in my career was quantum computing which is where I have ended up before I retire. Again, this is on the photonic side, trying to make room temperature single photon sources. That’s been quite successful, but we’re still working on getting them perfected so that we don’t need vast cryogenic units to cool down the machines. At the moment, the computers IBM and Google use are cooled by cryostats which work well but are quite expensive and very difficult to scale. They’re never going to be any use to anybody on a desktop, so you need something that doesn’t require that kind of industrial scale cryogenics.

Why lasers?

I just like them! I’ve always been hands-on since my father used to help me make things in the shed, so I never wanted to do theoretical research. I am very much an experimentalist and I’ve been doing hands-on research ever since.

I am very much an experimentalist and I’ve been doing hands-on research ever since.

Are there any moments or milestones in your teaching or research career that stand out as particularly meaningful?

Yes, I think one of the most rewarding aspects of teaching is working with exceptionally bright students. We always have very good students, but every so often, you come across someone truly brilliant and it’s an absolute joy. With students like that, it’s less about direct instruction and more about engaging with their ideas and pointing them in the right direction to refine their ideas.

What’s particularly gratifying is the feedback they give that they’ve had a great time. These students often inspire their peers too, lifting the whole group. One of the most important things we emphasise from day one is the value of collaboration: a strong cohort works as a team, while a weaker one tends to work in isolation. Helping them see the benefits of supporting each other makes all the difference.

On the research side, one of the best experiences I had was a sabbatical where I got to go to one of the top research universities in the world, the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne. I did some excellent research there and it also gave me the opportunity to think about what to do next. That was interesting because the thing about science is you can never do the same thing for your whole career: there’s always something new.

The thing about science is you can never do the same thing for your whole career: there’s always something new.

Tell us about your access work.

Because I’m Welsh, I’ve worked a lot with Access Cymru Wales. We used to go out to Welsh schools and encourage them to send pupils to Oxford from state schools. Those efforts ended when support for the initiative stopped. I still do a lot of access work though, mainly through scientific demonstrations at open days. I do The Cold Show using liquid nitrogen to make ice cream and I’ve done some TV shows, for example a show with Ben Miller on Horizon that explored the question: what is one degree? I’ve also done a talk on The Physics of Music with current Queen’s student Henry Coop who played the violin for me. The other talk I’ve done, of course, is The Wonderful World of Lasers, which is basically a fun light show.

How has Queen’s changed in 35 years?

It’s grown. There are more people in the SCR now and I think it’s a good thing because we’ve taken on more early career researchers. Also, although our undergraduate body has stayed fairly constant, the number of graduates has mushroomed, and that’s also a good thing because Oxford is a very powerful research global university. To stay at that level, we need good graduate students.

Another good thing we’ve done is to fundraise to support the tutorial system. It’s a very expensive way of teaching and so having the support of our Old Members is very valuable. The fact that we’ve endowed many Fellowships has been great; the Moffatt Fellowship in Physics is endowed and we are on the way to the second and final Fellowship being endowed. It’s a crucial way of maintaining things. When I announced my retirement, for instance, there was no question about my position being replaced; in fact, my replacement is already lined up (Dr Nakita Noel starts in October 2025). These decisions are not necessarily a given unless there are already funds set aside.

Another good thing we’ve done is to fundraise to support the tutorial system. It’s a very expensive way of teaching and so having the support of our Old Members is very valuable.

The quality of the accommodation has definitely improved. It was a little ropey when I first started! Also, while the food was always good, it’s now excellent.

Do you have any favourite food and wine when dining at Queen’s?

Well, wine is easy, because we had some very nice Burgundies. We were very fortunate to have an Old Member (Anthony Gwilliam, Modern History, 1948) who gave us his small wine collection when he died, including some wonderful claret, and this will be available for gaudies in the next 20 years.

I think food-wise, the biggest improvement has been the change in fashion. When I started in the 90s, there was still a hangover from the sort of heavy cream dinners of the ’80s and everything had lots of sauces. Now, it’s much more modern British: food with many influences from around the world. The variety is much better, as are the sensible portion sizes!

Are there any traditions that you’ll miss?

I think Queen’s wise, not too much, because I hope that the College will elect me as an Emeritus Fellow and keep inviting me back! The department is keeping me on as an Emeritus Professor for one year because it’s very difficult to just turn everything off suddenly, especially when you have collaborations with people in other subjects. So, I’m spending the first year of retirement handing over projects and moving equipment around.

What was your experience like of being the Pro-Provost for a term?

It was interesting in the sense that I met other Heads of Houses and you realise that most of them have not had an academic career. One of things about running an Oxford college is that there’s an awful lot of detailed administration within the University, and within the relationships between the University and the colleges. But that’s just the nature of the beast and perhaps having a different perspective is a good thing.

The second thing I noticed is just the sheer number of committees, events, and meetings that a head of house actually chairs. It’s a really full-on job.

What advice would you give to your successor or to any new Fellow starting at Queen’s?

I would say the main thing is to keep on top of the administration because there’s a so much of it. If you don’t do it as it comes up, it becomes overwhelming when you add in all the teaching you’ve got to do, and it can then disrupt your research. So having a good plan of how to run your time is quite important. Secondly, I would recommend developing a good relationship with the students.

What is your favourite place in the College?

I like the gardens. It’s really nice now that the weather is good, and just walking around the gardens is lovely; you can see the students enjoying them too.

I like the gardens. It’s really nice now that the weather is good, and just walking around the gardens is lovely; you can see the students enjoying them too.

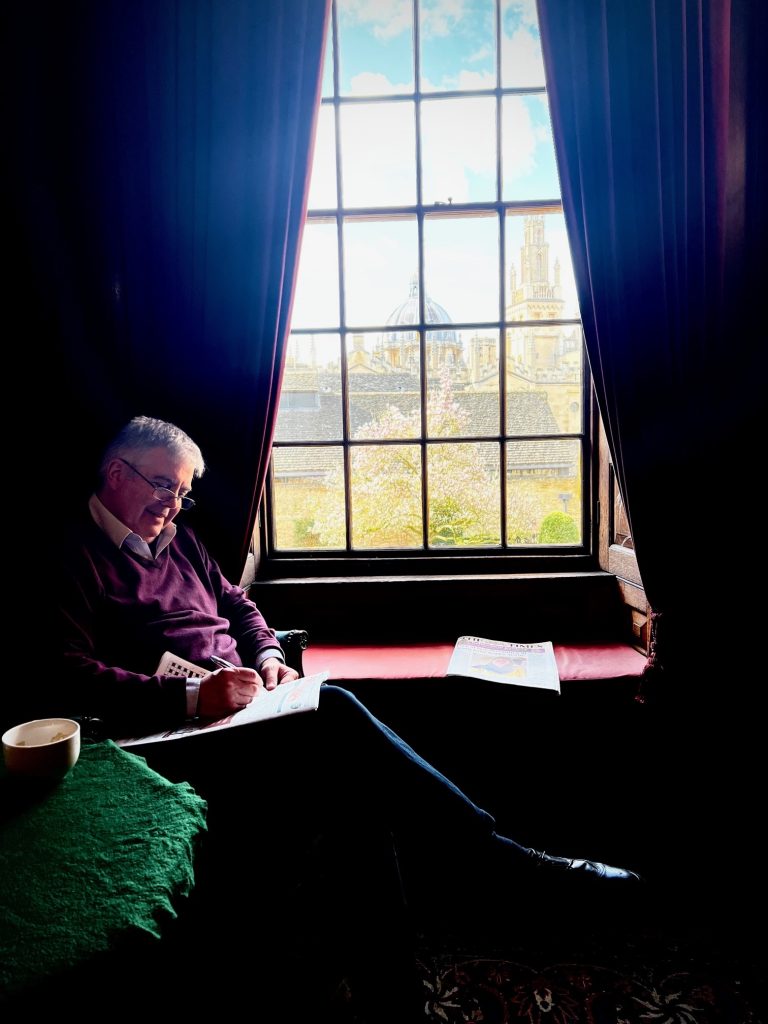

I also like the Upper Library. That’s a great place because it’s so quiet and nobody knows where you are! It’s a good place to hide and get work done.

What are you looking forward to in retirement?

My house in France and being able to go whenever I like, Brexit notwithstanding. Probably the worst thing that happened during my career here was Brexit. We used to have some fantastic students that came from Europe because they were being charged home fees and they pretty much all vanished because they won’t/can’t pay the much higher overseas fee. It’s a huge loss. It’s the same at the graduate level as well and this affects our research.

Can you recommend a book?

I recommend this for all my students: The Feynman Lectures on Physics by Richard Feynman. I recommend them not because they’re easily understandable, but because they are so left field. The work is a personal take from a very clever person on the whole of basic undergraduate physics. They are not to be approached lightly, and I tell my students to look at the lectures when they’ve done the topic. My advice is not to use them to try and learn the topic but read them afterwards to get another perspective: one that they should find interesting and might open their minds a little to a different way of looking at things.

Header photo: Matt Shaw