In 1934, newspapers around the world reported the startling news of an engagement between Japanese noblewoman Kuroda Masako to Ethiopian nobleman Araya Abebe. The match captured global attention, not only for its royal allure, but for what it symbolised: a bold, anti-colonial vision of solidarity between two non-Western empires.

In a new article published in Modern Asian Studies, Queen’s DPhil candidate in History, Federica Costantino, revisits this little-known episode to explore how it offered a radical challenge to racial hierarchies, inspired global hopes for a “non-white alliance,” and sparked resistance from colonial powers. We asked Federica to tell us more about the story behind the headlines and why this history still matters today.

Could you explain why this engagement made the headlines around the world?

Who doesn’t love a royal wedding? Even today, we are captivated by everything that happens to royal families and VIP weddings around the world! This particular engagement made headlines not only because it was heavily promoted by a savvy lawyer, Sumioka Tomoyoshi, who was in charge of combining it, but also because I believe it resonated with audiences in the 1930s for several reasons. Until that point, “royal” weddings had primarily been a European affair. No one in Europe would have batted an eye if, for example, the princess of Belgium married a prince in France in order to strengthen the respective royal families and alliance. However, this wedding featured two noble individuals, both of whom were educated to the highest standards, who defied racial boundaries to unite their empires-empires that were among the few remaining untouched by European colonisation at that time. The use of a distinctly European-and noble-practice to foster this alliance alarmed many European observers, particularly in Italy, which had colonial ambitions in Ethiopia. At the same time, it ignited hope among many non-European peoples who viewed this union as a potential step toward liberation.

Who doesn’t love a royal wedding?

How did you first come across this story and what drew you to it as a research subject?

As it often happens, it was a serendipitous encounter. While pursuing my MA at Columbia University in New York City, I mentioned to my then-advisor, Professor Gregory Pflugfelder, that I wanted to write a thesis on the role of women in the Japanese empire. It was quite an ambitious task! My advisor wisely suggested that I focus on a specific episode, pointing out that there might be a compelling story connecting a unique Japanese woman, imperialism, and my home country, Italy. At the time, I knew very little about Ethiopia, and nothing at all about a Japanese-Ethiopian connection before (and even against) Italy, so I delved right into this fascinating episode. As I conducted my research, I realised that the topic was much larger than I had initially anticipated, and I decided that it would be the research subject for my doctoral dissertation.

Your article explores the dream of a “transnational non-white alliance.” What did that idea look like in the early 20th century, and why is it significant today?

The concept of a “transnational non-white alliance” was greatly valued by many activists worldwide in the 1930s. At that time, except for Ethiopia and Japan, and a handful of other exceptions, the vast majority of Asia and Africa was under colonial rule. In non-colonised settings too, such as the US, racial inequalities were sadly a daily occurrence, and this episode provided them with hope that positive change could occur. Today, while we’ve made significant progress, it still isn’t enough. I hope my research can highlight how far we’ve come, as well as how much work remains to be done. At times, when I read historical sources from a century ago, they feel as if they could have been written today, reflecting a lot of exclusionary policies that are taking place in some countries even now.

What do you think was the reason for and/or impact of the marriage ultimately not going ahead?

I believe it was a combination of factors that led to this outcome. None of the countries involved recognised much potential in it, as the project was mostly championed by Sumioka Tomoyoshi and likeminded people who believed in an alliance based on skin colour. Additionally, Kuroda and Araya didn’t know each other personally, so they were drawn to the idea of it more than genuine love, which ultimately led to the demise of the idea. However, it’s worth noting that sometimes non-events can have the same impact as actual events! The fact that this engagement never turned into a wedding pushed so-called “coloured” alliances worldwide and inspired alternative visions of modernity from the US to Asia, which constitute the rest of my dissertation.

It’s worth noting that sometimes non-events can have the same impact as actual events!

The article touches on anti-colonial solidarity and racial politics. Were there moments in your research that particularly surprised or challenged you?

At the very beginning, as someone who was educated in Italy until university, I was completely unaware of these histories regarding Japan. I had knowledge of Pan-Africanism and Pan-Asianism from an anti-colonial light, but I hardly knew about Japan’s role in it. What surprised me was how there histories were absent from the “official” narratives we are taught. For me, Ethiopia was the place where my great-grandfather was sent to fight because he never wanted to join the Fascist party, but never a site linked to Japan. Conversely, Japan was to me one of Italy’s allies in the 1930s, and that was the extent of my understanding. Even when I began studying Japanese at university, I was unaware of these competing visions of pre-WWII modernity. Still today, I’m amazed at how many stories and histories there are still waiting to be uncovered! Needless to say, racial politics are often fraught with discomfort: I cannot recall how many times I had to translate blatantly racist pieces in order to situate this story in the context of the 1930s, and those sources always made me feel uneasy.

What sources did you use to piece this story together and were any particularly difficult to find or interpret?

I used a vast array of sources, including newspapers from around the world (the engagement was even advertised in Madagascar and Australia). Additionally, I relied on diplomatic records and one unique source: Kuroda Masako’s personal recollections of the event. While her writing is quite flowery and emphatic, it has been invaluable in capturing her authentic voice. Some journalists interviewed her, but as a historian you’re always aware that (in the 99% of cases) the male journalist might have misreported or twisted her words, especially since press in Japan was also heavily censored back then. To find her account, though, was more challenging than I expected. It was right at the onset of the pandemic, so I’m grateful to a lot of archivists who took the time to send me the hard copies by snail mail from Japan to Italy via the US. I also deeply appreciate the help of some colleagues in Japan who kindly agreed to scout that out for me in a moment in time when I couldn’t travel to see to it myself.

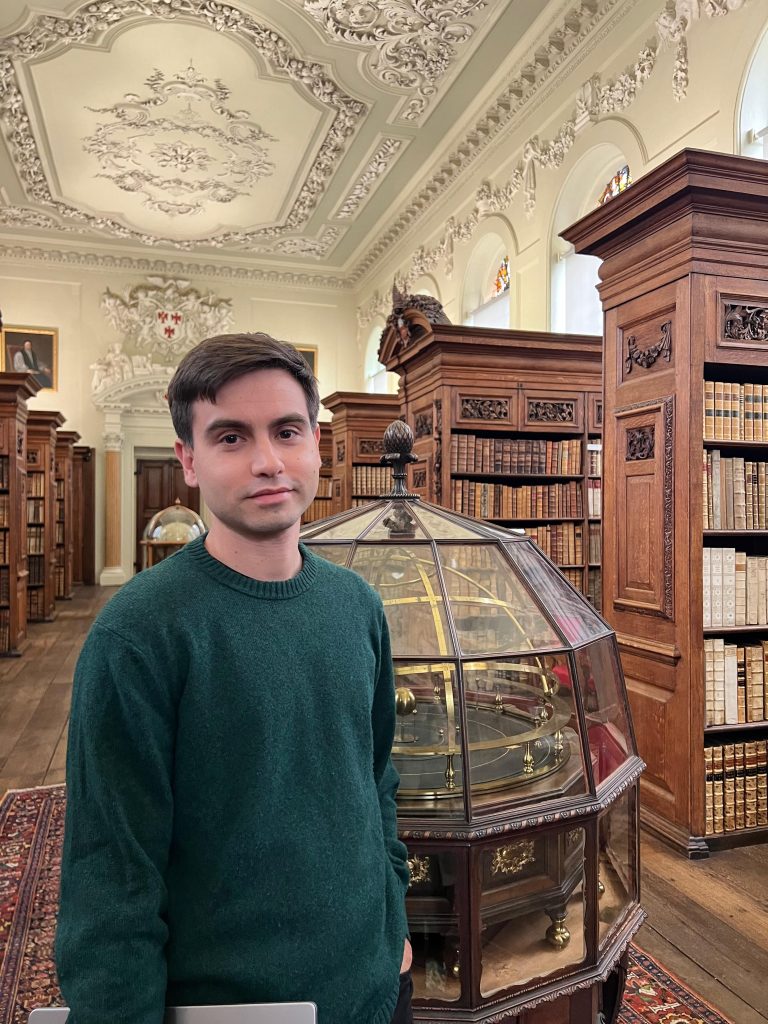

What brought you to Queen’s for your graduate work, and how has the College shaped and supported your academic journey so far?

Queen’s has an excellent reputation for Japanese studies, and I couldn’t be happier anywhere else due to the support I’ve received. The College has funded several research trips, including one to New York City, which was essential for my dissertation. My College Tutor, Dr O’ Brien, is a gem and always available to help.

Who or what has inspired your interest in modern Asian studies and transnational history?

It is kind of a familiar story: a little girl who loves anime gets catapulted into Japanese culture. From that, I started to feel increasingly attracted to a world so different to mine. I started taking Chinese classes because that’s what was available to me whilst growing up, and I just haven’t stopped learning about East Asia since then. In graduate school, it was the Kuroda-Araya engagement that sparked my interest in transnational history. When I started seeing that everything was interconnected, I realised I wanted to study with Professor Sho Konishi, my current advisor at Oxford, who’s one of the leading experts in Japanese transnational history.

If you could speak to a wider audience, beyond academia, about this story, what would you want them to take away from it?

I would tell them that this is undeniably a history of those who didn’t realise their dreams—losers, as some might call them—but their stories are just as important as the narratives of the “official” winners we study. When we discuss unrealized dreams, unsuccessful endeavours, or failed projects, we must remember that these were once active parts of history. The individuals behind these dreams were not merely dreaming; they were actively fighting for the ideas they believed in. Ultimately, even if you don’t achieve success, don’t worry; there will be someone who finds your story valuable. The world is filled with potential great stories just waiting to be discovered.

How do you think history can help us navigate racial politics today?

History is, in a classic way, “magistra vitae” (life’s teacher): I firmly believe we can learn valuable lessons from history that can be applied today. For instance, history teaches us that exclusionary practices based on race and ethnicity have consistently failed in the past, and I believe they will continue to do so in the future.

I firmly believe we can learn valuable lessons from history that can be applied today.

What are you working on next?

I am currently finalising my doctoral dissertation while also refining a new article inspired by Sumioka Tomoyoshi’s vision of racial equality. To Tomoyoshi, Ethiopia was merely the starting point; he envisioned a “Destiny Community” that transcended the East/West divide, rejecting any racial or colour boundaries. This community included countries such as Japan, Hungary, Egypt, and many others.

Can you recommend a book?

A book in Japanese history that changed my life was Anarchist Modernity by Sho Konishi. That was the book that made me realise I wanted to work with him as it’s a book that really challenges whatever you think you know about intellectual history of Modern Japan.